Sharif carrying the torch of opposition in Pakistan

- Share via

RAIWIND, PAKISTAN — As this country’s political opposition looks for a leader after last week’s assassination of Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif may be the last man standing.

And his eyes are fixed upon a single goal: to get rid of his archenemy, the man who kicked him out of office in a military coup more than eight years ago, President Pervez Musharraf.

Only a few months ago, Sharif was languishing abroad, a deposed two-time prime minister relegated to fanning the embers of his career in bitter exile. Now, he’s back with a vengeance, campaigning for his party in upcoming elections and assuming his role as the only politician left with a credible national profile after Bhutto’s slaying, which transformed the political landscape in Pakistan.

Sharif’s heightened stature is good news for his supporters, especially here in populous Punjab province, his longtime power base. But it raises hackles elsewhere, including Washington, where the White House regards him as too friendly with Islamic extremists and too hostile toward Musharraf, a close ally in the U.S.-declared war on terrorism.

Sharif is also a controversial figure at home, where he faces ongoing corruption charges and is barred from running for parliament or becoming prime minister, for now, because of a separate case. But he has been busy consolidating support for his party and playing the senior statesman.

Even his critics acknowledge that he has acted with grace and dignity in the aftermath of the attack on Bhutto, with whom he once carried on a venomous rivalry.

“I think we have buried the bitterness of the past. We buried it five years ago, maybe a little bit more than that,” Sharif said Thursday in an interview at his estate in Raiwind, outside the eastern city of Lahore.

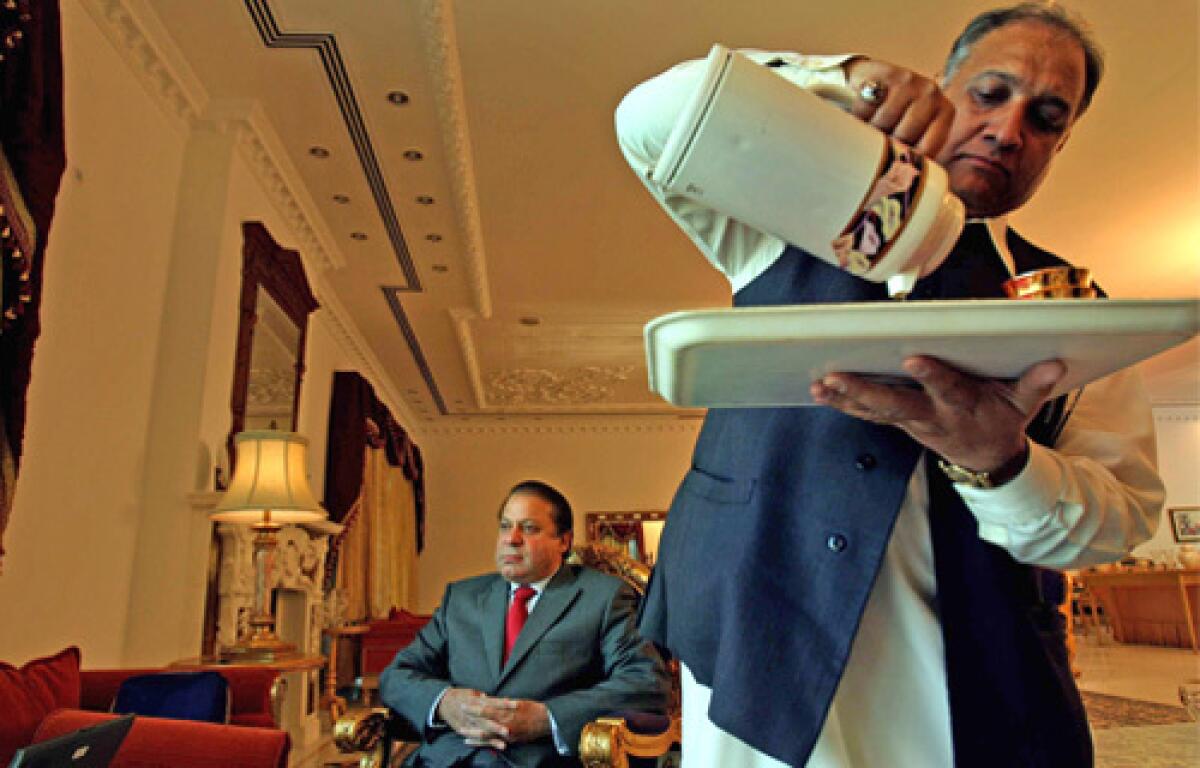

In a dark suit and red tie, he sat in a cavernous living room whose entrance was flanked by two stuffed lions, in homage to his nickname, the “lion of Punjab.” A massive crystal chandelier hung overhead, sending light refracting through a collection of cut-glass bowls and vases.

“We became friends, Benazir Bhutto and myself,” he said. “And we both jointly decided to launch a struggle against dictatorship.”

A wealthy industrialist, Sharif, 58, is trying to make common cause with Bhutto’s Pakistan People’s Party, or PPP, in restoring democratic rule to his homeland. Part of that makes pragmatic sense: His Pakistan Muslim League-N hopes to ride the coattails of the PPP, which is expected to garner a significant sympathy vote in parliamentary polls Feb. 18.

Working together, the two parties might be able to challenge Musharraf or, with a two-thirds majority, attempt to impeach the president.

There is no doubt that Sharif is on a single-minded campaign to rid Pakistan of Musharraf, whose autocratic regime he blames for plunging the nation into turmoil. During his second term as prime minister, from 1997 to 1999, Sharif picked Musharraf as chief of the army, only to see the then-general usurp him, toss him in jail and banish him to Saudi Arabia.

“This one man is playing havoc with the state. This one man is guilty of abrogating the constitution. This one man is guilty of reducing the parliament to a rubber stamp. . . . It is a great shame for me as a Pakistani to see these things happening,” Sharif said.

“I stand for democracy; I stand for the rule of law; I stand for independence of judiciary; I stand for freedom of press and the media; I stand for the fundamental rights of the 160 million people of Pakistan,” he said. “I think it’s a very good stand, a very noble cause.”

For some, such ringing liberal democratic rhetoric from Sharif, which he has repeatedly sounded since being allowed to return to Pakistan in November, is laden with irony.

From the time he was chief minister of Punjab in 1985, almost until his ouster from the prime minister’s office 14 years later, Sharif owed much of his position to the ties he cultivated with the ruling establishment, including the all-powerful military.

His government was accused of routinely threatening journalists. The police once abducted a well-known editor, allegedly on Sharif’s orders, because the publication displeased him. Pakistan’s biggest Urdu-language daily, Jang, was at times reduced to publishing single-page editions because of harassment.

Pro-Sharif activists also stormed and ransacked the Supreme Court, whose chief justice, a Sharif foe, eventually felt forced to resign from the bench.

“When he says, ‘We stand for freedom of the judiciary; we stand for nonintervention of the military in the government,’ he is standing against everything that he himself did,” said Muhammad Badar Alam, a political writer.

And the comeback leader who says he supports the rights of fellow Pakistanis maintains a lifestyle to which only the tiniest handful of them can relate.

Sharif is a multimillionaire who many think amassed some of his riches through shady deals. His spacious living room comfortably fits seven sofas and could house as many poor families. Surrounding his mansion are grounds so expansive that his two stuffed lions could conceivably have been shot on-site. (They are from Africa.)

Critics are skeptical of his makeover as a for-the-people democrat, and gossip columnists have poked fun at his apparent makeover with hair plugs.

Sharif defends his record in government, saying that he strengthened the role of parliament vis-a-vis the president and implemented market-oriented economic reforms. But he professes to having had an epiphany during his time in detention.

“I was kept in jail for 14 months in solitary confinement, and I was left to ponder what led to such a terrible punishment,” he said. “I was elected by the people of Pakistan. I was accountable to them and not [to] a military dictator.”

He added: “The roots of democracy strengthened in my heart and soul. And I thought that I will now launch a struggle for the restoration of rule of law to put an end to this law of the jungle.”

But Sharif remains a source of concern because of his religious views, which prompted an attempt in 1998 to pass a constitutional amendment imposing strict Islamic law in Pakistan. The move, widely regarded as a ploy to consolidate power and to steal the thunder of Islamists, was blocked by lawmakers.

His ties to Islamist parties have sparked fear in Washington that he would be less than a full partner in the battle against Al Qaeda and the Taliban, although some analysts say Sharif is no fundamentalist.

“He is a conservative religious person, and he wants to be seen as a conservative religious person, but this would characterize the majority of Pakistanis. They are religious, but at the same time they are not with the politics of the religious parties,” said Rasul Baksh Rais, a political scientist at Lahore University of Management Sciences.

“I don’t know him well enough,” President Bush said of Sharif at the end of November, adding that he “would be very concerned if there was any leader in Pakistan that didn’t understand the nature of the world in which we live today.”

Sharif counters that, as prime minister, he enjoyed good relations with the Clinton administration. And he scoffed at the notion that Musharraf had been a valuable ally in the battle against terrorism, blaming him instead for exacerbating the problem with his authoritarian ways.

“Things have taken a dangerous turn these days. Now Pakistan itself is in the grip of terrorism,” Sharif said. “Democracy is the only answer to these problems, to extremism, to militancy, to terrorism.”

Until last week, the U.S. had pinned its hopes on a power-sharing deal between Bhutto and Musharraf, thinking that it would result in a pro-Western government. But Bhutto’s assassination doomed that plan, leaving the U.S. scrambling for an alternative, even as Sharif’s refusal to negotiate with Musharraf has boosted the opposition leader’s standing in the eyes of those Pakistanis who agree that the president is a dictator.

“Mr. Bush must not equate Pakistan with Musharraf,” Sharif said. “This idiocy is giving rise to anti-American feelings in Pakistan.”

His party appeals to conservative, urban, middle-class voters, whereas the PPP’s base lies among the rural poor. And though Sharif lacks the cosmopolitanism of Bhutto, who was educated at Harvard and Oxford, that has helped him at home.

“What really benefits Mr. Nawaz Sharif is a ‘made in Pakistan’ image, which really fits with raw middle-class Pakistani nationalism,” Rais said. “They have a feeling he is one of them culturally.”

His decision to conduct nuclear tests in 1998, in response to India’s tests, was met with alarm in much of the world but widespread celebration in Pakistan’s streets.

Still, virtually no one expects the Pakistan Muslim League-N to win next month’s election. His party is disorganized, and on the hustings he has none of the charisma of Bhutto, who could draw thousands to PPP rallies.

But he is trying to cast himself as the principled voice of opposition to Musharraf -- and could succeed, analysts say.

“He is truly the only national leader left who can claim support in every province of the country,” Rais said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.