In life, Mexican cartel boss was revered as a saint

- Share via

MEXICO CITY — If nothing else, the slaying of cartel boss Nazario Moreno Gonzalez by Mexican soldiers may have burst the bubble of mysticism that had made him one of the stranger figures to emerge in the country’s drug war.

Moreno, whose nicknames included “El Mas Loco” (“The Craziest”), was a founder of Michoacan state’s La Familia drug cartel and its offshoot, the Knights Templar — groups that have moved massive amounts of methamphetamine and other drugs north to the United States.

In Mexico, the groups have run extensive extortion rackets, corrupted dozens of local governments and engaged in blood-drenched warfare with federal troops and rival drug gangs, all the while spouting Moreno’s mix of evangelical Christianity, self-help advice and the writings of Lebanese American poet Khalil Gibran.

Moreno fancied himself a protector of his people and an enforcer of rules. Among other things, he forbade the use or sale of methamphetamine on his home turf, insisting that it only be shipped to the U.S. As cracked as that moral code was, it could feel like something to cling to in an often lawless land, and it made Moreno a kind of legend.

Although it’s unclear whether his death in Sunday morning’s shootout will help quell the violence in western Mexico, it is likely to help President Enrique Peña Nieto sell the argument that his administration is fighting a smarter and more sophisticated drug war than that of his predecessor, Felipe Calderon.

When Peña Nieto took office in December 2012, there was a fear that he might go soft on the cartels in an attempt to calm the violence. But now, two mythic drug lords have been felled in a matter of weeks. A joint U.S.-Mexico operation nabbed Sinaloa cartel boss Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman on Feb. 22.

Jorge Chabat, a professor at Mexico City’s Center for Economic Research and Teaching, said that at the very least, the elimination of the two capos shows that “there is a part of the Mexican state that is indeed effective and is capable of functioning.”

It was the bumbling of the federal government that helped turn Moreno into a folk saint in the first place. In December 2010, Mexican authorities claimed they had killed Moreno in a shootout. They hadn’t, and soon Moreno was making appearances all over Michoacan, his spiritual powers growing in the eyes of campesinos who began praying to him and setting up shrines in his honor.

One printed invocation dug up this week by Reforma, the Mexico City newspaper, went:

Blessed light of night

Defender of the sick

St. Nazario, saint of ours

I always entrust myself to you.

Mexican authorities say Moreno was finally gunned down — for real, this time — by federal troops in a rural Michoacan municipality Sunday. His body was recovered and his fingerprints checked against a government database.

The effect Moreno’s slaying will have on the cartel-related unrest that has gripped Michoacan, and become a major source of embarrassment for the government, remains to be seen.

Last year, “self-defense” militias sprang up in the rural state and threatened to confront Moreno’s Knights Templar directly, given the lack of government action. Outside the village of Buenavista Tomatlan, the vigilantes trashed a shrine to Moreno.

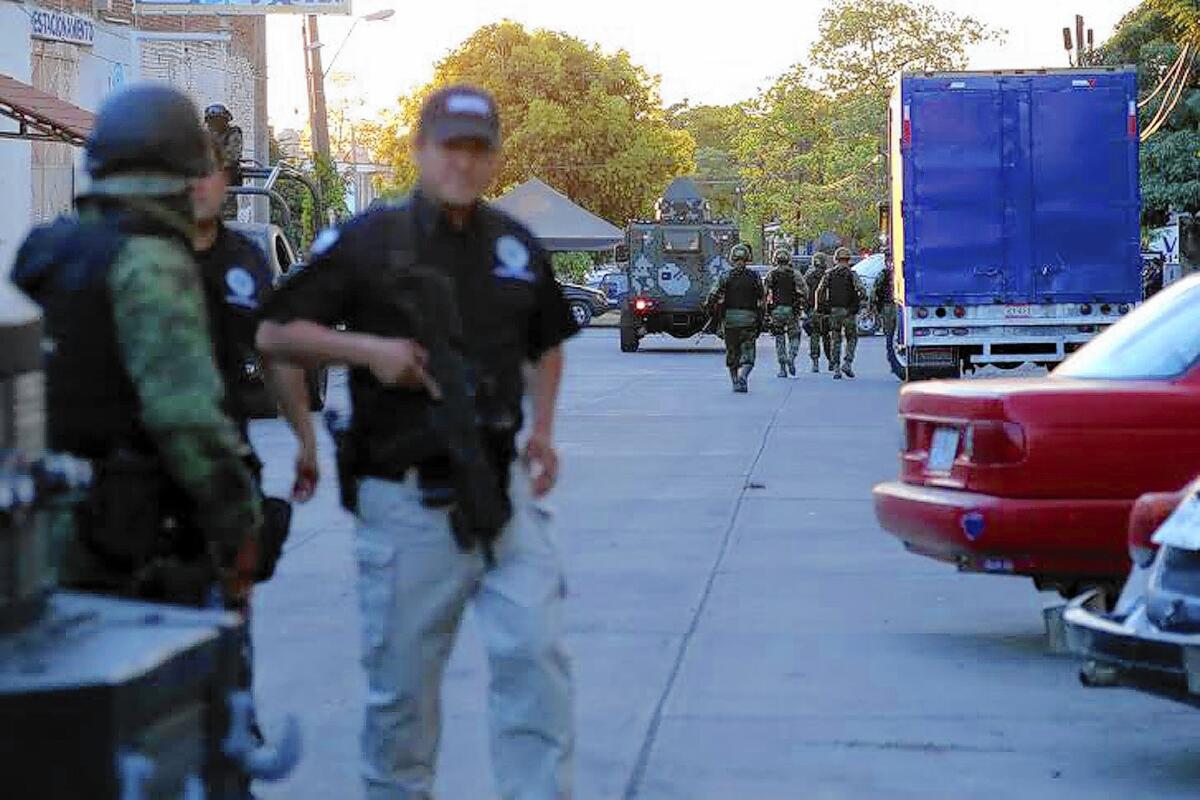

In January, Peña Nieto sent a massive deployment of troops and federal police to avert a conflagration between the two groups. Since then, those troops and police have been rounding up suspected cartel members, often acting on tips from cooperating vigilantes.

The heightened presence appears to have led to the realization that Moreno was still alive: Monte Alejandro Rubido Garcia, head of the National Public Security System, said the government was first tipped off to the possibility Feb. 7 when authorities patrolling the area arrested a man carrying drugs and weapons who told them he worked in “direct service” to Moreno — one in a chain of clues that eventually led them to the capo’s door.

The encounter suggests that Moreno was acting as more than a spiritual leader for the group. If so, his death could deal an operational blow to the Templars.

At the same time, the federal government said it has recently reestablished its control over the port of Lazaro Cardenas, on Michoacan’s Pacific coast. The Templars long exerted a strong influence at the port, controlling the importation of drugs and methamphetamine precursors and shipping out minerals the cartel extracted from illegal mines — all major sources of income. On March 3, the government announced that it had seized 119,000 tons of illegally mined iron at the port that the cartel had been hoping to ship to China.

Other Knights Templar leaders have also been targeted.

Late last month, troops killed a local cartel leader named Francisco Galeana, also known as “El Pantera.” A few days later, the government announced the capture of Luis Alfredo Aguilera Esquivel, a cartel member and son of Servando Gomez Martinez, a.k.a. “La Tuta,” the man presumed to be the leader of the cartel’s day-to-day operations.

Then, on Friday, authorities arrested 15 people on suspicion of extortion and kidnapping, including cartel leader Abraham Zamora Zamudio, also known as “El 69.” The self-defense groups have applauded these law enforcement victories, which could serve to break up the cartel and lead the vigilantes to return to their homes and farms.

The vigilante groups have created problems too.

The federal government had to send troops and federal police Monday to the town of La Ruana, near Buenavista Tomatlan, to prevent an altercation between two quarreling self-defense factions, according to a radio news report.

Chabat, the professor, warned that Moreno’s death may not make a big difference in the effort to fix Michoacan. He noted that a number of other leaders remain at large.

In many places, the drug gangs have made deep inroads into the local power structure. In the nearby state of Guerrero last month, the head of the chamber of commerce in the state capital, Chilpancingo, accused the mayor of being in league with crime gangs and of trying to assassinate him — allegations the mayor strenuously denied.

The real change in Mexico, Chabat said, will come not from counting scalps but from solving the long-term problems that enable drug cartels to flourish.

Local governments will need to be armored against corruption. Local law enforcement agencies will need to be strengthened to fight off local crime bosses. And gains in education and living standards must be made so that a bloodthirsty drug dealer is not revered as a saint.

Cecilia Sanchez of The Times’ Mexico City bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.