Evacuated after Hurricane Irma, many of the 1,800 people of Barbuda want to go home. But the island is in no shape to take them back

- Share via

Reporting from CODRINGTON, Barbuda — It was a grim homecoming.

Crumpled sheet metal, shattered glass, snapped wooden planks, clothing and remnants of refrigerators, stoves and flat-screen televisions were strewn where a village bustled before the day in early September when Hurricane Irma visited this tiny Caribbean island.

Days after Irma left, another hurricane seemed poised to strike Barbuda, and all 1,800 people were ordered to evacuate to neighboring Antigua. The second storm missed. But a month later, residents were trickling back to see what they could salvage.

“When I look at it, all I can say is that we’re lucky to be alive,” said 53-year-old Devon Christian, who lost one of his two houses as well as his job. The storm decimated the Coco Point Lodge, the luxury resort where he tended bar for more than three decades.

He said he was determined to rebuild his life there: “This is my home, and that’s where I want to be.”

It’s the predominant sentiment among the people of Barbuda, the vast majority of whom remain on Antigua, 35 miles to the south. But the damage is so extensive that officials are dissuading the displaced from moving back anytime soon — leaving them largely dependent on the generosity of their hosts.

The two islands, both former British colonies, were granted independence in 1981 as a single country known as Antigua and Barbuda. But it is unclear how long the goodwill of the 93,000 residents of Antigua will last. The Barbudans are already straining the health, education and social service systems there.

“People become overwhelmed with the enormity of the help they have to provide, and they have to go into their own resources,” said Cleon Athill, vice president of a grass-roots citizen group called the Movement, which has been collecting donations of food, clothing and other supplies. “People have been coming and saying, for example, ‘I have two people in my house; all my food has run out. Can you please provide me with some?’ ”

‘Sense of normalcy’

Shellshocked from the storm, Gloria Cephas arrived on Antigua with six of her children and no possessions other than the clothes they wore.

Her savior was a property manager, James Richards. After a church member called to ask him for help housing evacuees, he arranged for Cephas to live for free in an upscale two-bedroom townhouse with a deck overlooking the harbor in the capital, St. John’s.

“It was something I had to do,” Richards said. “Going through such a traumatic experience, it will give families some sense of normalcy. They have a roof over their head.”

Cephas’ eyes welled with tears as she described the devastation back home, a place where nearly everything was within walking distance — markets, schools and jobs — and everybody knew everybody else.

“I’m hoping for Barbuda to be rebuilt,” she said. “I’m hoping to get back my house. But for right now, we have no choice but to stay. We miss home, but what do we return to?

“The best thing for us is to stay put in Antigua until we can get something sorted out,” she said.

Richards said the family could remain until at least the end of October.

About 320 people wound up in shelters, including the local cricket stadium. But most were taken in by relatives, friends or strangers.

Alaida Deazle and her husband, son, daughter, son-in-law and three grandchildren moved into the apartment on the top floor of Morvel Francis’ house.

“When I heard of the terrible disaster … I was absolutely horrified,” said Francis, a 67-year-old social worker. “I just wanted to help as many people as possible.”

The Deazles had “become like a part of my family,” she said.

“Thank God for Mrs. Francis,” Deazle said. “She came just in the nick of time. God sent her.”

The sudden influx on Antigua, however, has not been easy to provide for.

Roughly half of the newcomers are adults who need to find work. Schools must accommodate an extra 600 children. The elderly need medical care.

The strain has been compounded by the arrival of hundreds of people from neighboring Dominica, which was ravaged by Hurricane Maria on Sept. 18. Other storm refugees have come from St. Martin and the British Virgin Islands.

Michael Joseph, president of the country’s Red Cross Society, called the situation a humanitarian crisis and predicted that Antiguans now playing host could become victims of their own generosity.

“They now have an increase in electricity, water, transportation costs,” he said. “This is going to increase the vulnerability of families that are already facing their own personal challenges.”

The government is trying to ease the burden by fixing up an old hotel and other buildings to turn them into long-term housing.

“Once these are finished, we will move the families in there, which will give them some greater dignity in terms of the present space that is available now,” said Philmore Mullin, director of the National Office of Disaster Services.

But allowing people to get too comfortable comes with its own risk for officials: The more the newcomers settle in, the less likely they may be to leave.

“We’re not in a hurry,” said Charles Nelson, 60, who was staying at the cricket stadium with his partner and their four children, ages 5 to 12. They had to leave their dog behind in Barbuda.

“We would have to rebuild from scratch,” Nelson said. “The kids are in school, and they like it here.”

An ‘uninhabitable’ island

Not that Barbuda could support its own population right now.

“The main infrastructure is totally devastated,” said Arthur Nibbs, the minister of Agriculture, Lands, Fisheries and Barbuda Affairs. “There’s no electricity, there’s no water. There’s no security. It cannot be more challenging. My advice to them is that they should not be in a rush to return.”

In an interview with The Times, the nation’s prime minister, Gaston Browne, described the 62-square-mile island — best known by outsiders for its pink beaches and tropical seabird sanctuary — as “uninhabitable.”

He said that at least 90% of all homes suffered some type of damage and that most of those would require significant reconstruction or were destroyed. Preliminary estimates have put the cost of rebuilding at $250 million, more than 12% of the country’s gross domestic product.

The island’s main inhabitants now are brigades of government workers sent back to clean debris from the streets, spray against mosquitoes and pick up the carcasses of cattle, sheep, donkeys and dogs that were among Irma’s victims.

To provide for the workers, the island’s main supermarket, bakery and pharmacy have been fast-tracked for renovation, Mullin said.

Repair work is also scheduled to begin soon on buildings that suffered minor damage and can be made habitable relatively easily, he said. The government also plans to provide tents — and possibly prefabricated buildings — in which Barbudans could live while fixing their homes. Supply shipments to Barbuda have been hampered by silt that was deposited during the storm and is blocking barges and other large vessels from docking on the island.

Most of Barbuda’s only hospital was destroyed. An emergency medical post has been set up in one section of the building that survived, according to the country’s health minister, Molwyn Joseph. Medical technicians were rotating into the facility for two days at time.

Browne, the prime minister, has a grander vision for Barbuda: rebuilding it as an eco-friendly island and establishing a medical tourism industry that would draw patients with the island’s warm weather and discount prices on healthcare. Talks were underway with various U.S. hospitals, he said.

The initiative would help develop an economy on Barbuda and ensure residents eventually go home, he said.

“It is in our interest to get them back there as soon as possible,” Browne said. “We need them to be part of the rebuilding.”

Carl Jason Francis was ready to take up the call.

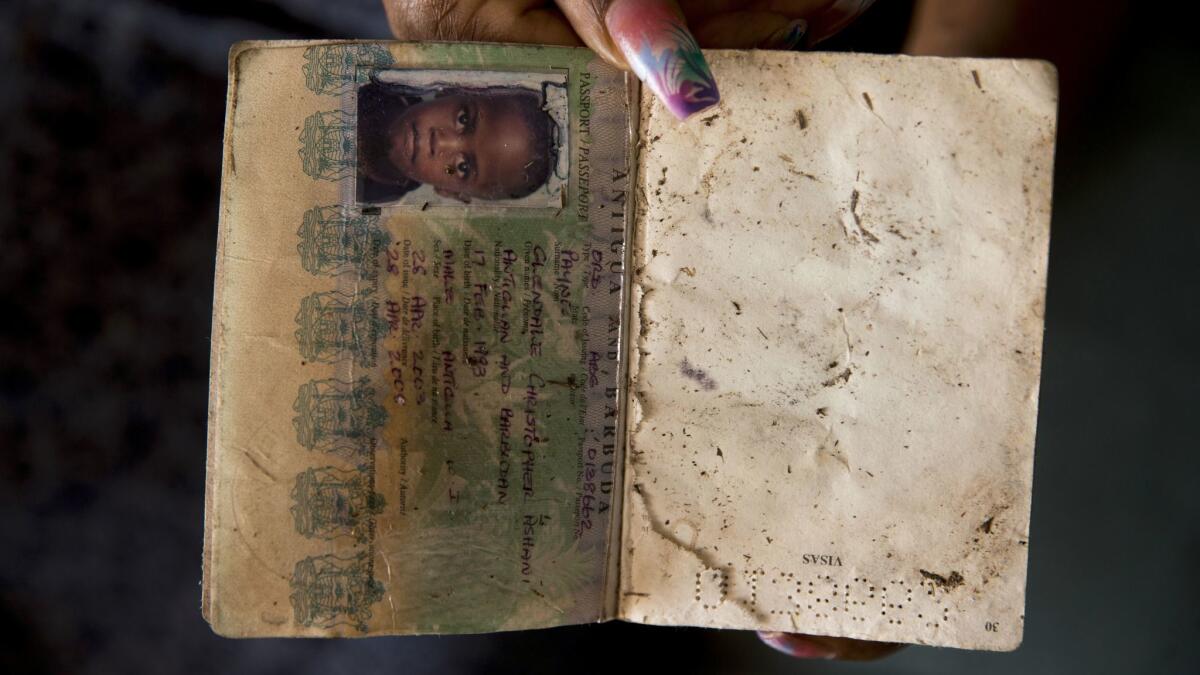

He and his wife were evacuated to Antigua by helicopter after their 2-year-old son, Carl Francis Jr., was blown out of his godmother’s arms during the storm and killed — the lone death on Barbuda from the hurricane.

The family buried the boy in late September — on Antigua.

“It’s not easy being over here, when you’re accustomed to Barbuda,” said Francis, 50. “I’m going back to clean up.”

This story was reported with a grant from the United Nations Foundation.

For more on global development news, see our Global Development Watch page, and follow me @AMSimmons1 on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.