China quake survivors still wait for word

- Share via

Reporting from Hanwang, China — In the 11 months since China’s devastating earthquake, Wang Tingzhang and his wife have been transformed from docile, law-abiding citizens into defiant troublemakers, at least in the eyes of authorities.

Along the way, they’ve been pushed, punched, wiretapped, tailed and detained.

Their offense? Asking too many questions about what happened to their only child, an 18-year-old girl who was buried under the rubble of her high school in the May 12 earthquake here in Sichuan province.

In the early weeks after the magnitude 7.9 quake, Beijing was widely applauded for its efficiency, compassion and openness in handling China’s worst natural disaster in decades. But since then, the curtain has fallen.

Even the death toll is shrouded in secrecy. Although about 70,000 people are believed to have died, the government has yet to release an official toll. DNA testing that could identify thousands of victims has stalled, with no explanation from authorities.

Parents and researchers asking about schools that collapsed have been detained and harassed.

Tan Zuoren, a literary editor and environmentalist who was creating an archive of children killed in collapsed schools, was arrested last month on charges of subverting state authority, according to Amnesty International. The rights organization said his dog was stabbed and his computer stolen as well.

In the last few weeks, more than 10 volunteers working on a similar project with Ai Weiwei, a Beijing artist best known as one of the designers of the so-called Bird’s Nest Olympic stadium, were detained while doing research in Sichuan. One was beaten last weekend trying to photograph a school.

“Those in power view anybody asking questions as challenging the legitimacy of the government,” said Ai, who has registered 5,000 names of the dead and is still counting. “In the case of my volunteers, you could say they deserved it. . . . But for the parents, most of whom are peasants and ordinary people, to be followed, harassed, wiretapped -- this is very scary for them.”

There’s a growing clamor for a complete listing of victims’ names, ages and details of how they died so it can be determined whether a disproportionate number of schools collapsed compared with other buildings.

“If we bury the names of the dead, we cannot claim to have human rights in China,” the Southern Metropolis Daily wrote in a hard-hitting editorial published Wednesday.

The Chinese government pledged last week to register “the names of the people who died or disappeared in the earthquake and make them known to the public.”

To Wang Tingzhang, struggling for 11 months to get information about his daughter, Wang Dan, the Chinese government’s promises sound hollow.

“They pressure us. They try to control us. They follow us and listen to our phone calls,” said Wang, his soft voice rising. “But even if they kill us, it doesn’t matter because we’ve lost our daughter. . . . We’re not scared of the government anymore.”

Wang, a polite man with a ruddy complexion and a shock of dark hair creeping low on his forehead, stands about 5 feet, just a little taller than his delicate-featured wife, Liu Shengying. They live with his mother in a shack they made themselves out of blue tarpaulin and bamboo to replace their destroyed home.

Although both are from large peasant families, they were true believers in the Communist Party and its limitations on family size. Without complaint, they had just one child, and poured all their savings and ambition into her.

“Girl or boy, I didn’t care,” said Wang, 44. “I didn’t get much education myself. I would break my bones working or sell my house to make sure my child had a future.”

On the day of the quake, Wang was working out of town at a plastics factory, but he flew home immediately. By the time he reached Dongqi Secondary School, where his daughter was enrolled, it was 3.30 a.m., 13 hours after the quake. The 1970s-era building had collapsed, burying the students under four floors of concrete and steel girders. Wang pitched in, helping to pull out the mangled bodies, looking in vain for his daughter.

With no refrigeration to preserve the bodies, those not immediately identified were taken away for a mass burial on a nearby mountain. But the volunteers photographed their faces, jotted down information about clothing and body size on index cards and snipped hair to be filed away in plastic bags for future identification.

A month later, Wang and his wife got a call from the Hanwang municipality, where they live, asking them to submit blood for DNA testing. They provided the blood, and then waited. And waited.

Every few months they visit the municipal office or the education department to ask when or even whether they might expect results.

“I realized that my daughter was dead. But there was still this fantasy that somehow the phone was going to ring,” Liu said. “We wanted to get confirmation.”

The couple had other questions about the school, where 240 of the 1,200 students were killed. Why had no repairs been made to the building, which was so weak that students were instructed not to run in the corridors? What had happened to nearly $6 million that the Dongqi auto company had donated to the municipality for rebuilding.

A group of parents went to city hall in October, hoping to get answers from officials. Instead, they found the entry blocked by police officers, who kicked and punched them as they tried to get near.

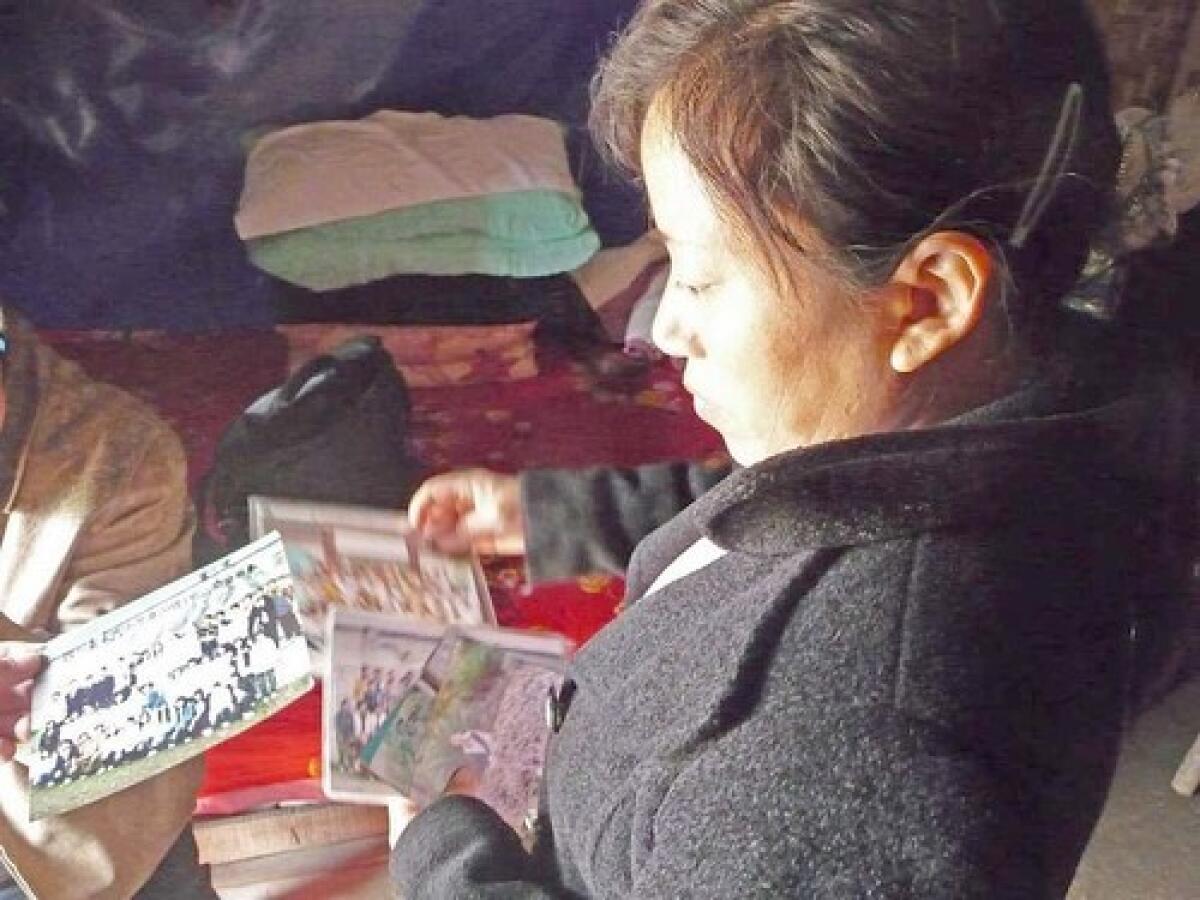

In November, Wang and his wife went to the school to meet other parents from their daughter’s class and compare notes. They ran into one of their daughter’s classmates -- one of four in the class of 50 who survived -- and were happy when she told them how well their daughter had been doing in school.

Chatting away, they didn’t realize at first that they were surrounded by police officers dressed in full riot gear. They say the officers herded all the parents onto a waiting bus.

“We’re going to take you to the municipal offices and they’ll answer your questions,” Wang said the police told them.

Instead, they were taken to the police station and locked up. They remained there from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m., when officers told them they couldn’t go home until they signed a statement confessing that they had “surrounded the school and disturbed the public order.” Exhausted and hungry -- they hadn’t been allowed to eat -- all the parents signed.

Since then, every time that they’ve tried to meet with other parents, police have discovered their plans immediately.

“Our telephones are tapped,” Wang said.

His wife, who is five months into a difficult pregnancy, doesn’t leave home often. Wang goes regularly to the municipal office to ask when DNA results will be available and gets answers such as, “It’s complicated. It takes a long time.”

The Chinese Ministry of Civil Affairs announced a week after the quake that it was setting up a DNA database for unidentified victims. Half a dozen companies and universities also volunteered their expertise and set up a website to help match victims and families. The site was shut down a few weeks later, along with all other nongovernmental DNA testing projects for quake victims.

“I don’t know why. The reasons were never made clear,” said Deng Yajun, head of the Beijing Institute of Genomics, a respected forensic research firm.

But Wang has his own theory. “Now it’s almost a year and I’m beginning to wonder,” he said. “Are they really doing DNA testing, or was this just something to tease us? It feels like they don’t want outsiders to know the death toll.”

Eliot Gao and Nicole Liu of The Times’ Beijing Bureau contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.