‘We even smile at these stories from our parents because it seems so . . . absurd’

- Share via

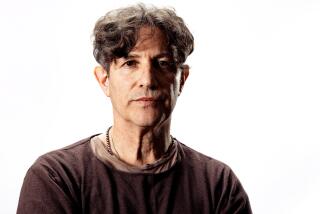

Reporting from Berlin — Valentin Geissler has no memory of the wall.

He was just 10 months old when it fell, and most of its traces have by now disappeared. But it still hovers over the city like a ghostly presence.

“Sometimes I can see in the city where the wall was. . . . I don’t remember specifically when I was told [about it]. I guess I kind of grew up with this knowledge.”

But the wall didn’t play a big role in his childhood, not the way it had loomed over the lives of his parents. The restrictions, privations and other hardships of life in the former East Berlin are an alien concept.

“A few things are quite hard for me to imagine. My father had to trade stuff to get certain records for his record player. These things were really hard to get. . . . Money wasn’t the problem; it was where you would get it. This is bizarre to me.”

Though the Berlin Wall was gone, the division of the city continued to be felt as Valentin grew up.

“The schools closed. After the wall opened, people stopped having children, so all the classes after me were pretty empty. They closed one school after another, so I had to change schools. I probably went to four different ones. . . .

“You could always tell which teacher was from which part of Berlin. They had different styles of teaching, and often they disagreed with each other. . . .

“There were certain methods that only a western teacher would try. They’d usually want the class to be quieter; they had a more strict style, while the teachers from the east seemed more interested in getting to know the children.

“On the other hand, they had old teaching methods, such as that you learned vocabulary only from the textbook. The teachers from the west would try new things they picked up in a course somewhere. . . .

“The west teachers would use different words from the eastern teachers. I knew the eastern words because I grew up in the east. . . . It still happens now.”

But those differences weren’t explored in a systematic, educational way. Interestingly, the history of a divided country and a divided Berlin does not figure prominently in the curriculum of many German schools. Surveys have shown that young people have only hazy ideas about their nation’s recent past, often informed more by what they have seen on television or in movies than from textbooks.

“At school the focus of history is more the Third Reich. Even in primary school they start with this. Only when I did Abitur [college prep] did they specifically talk about DDR [Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or German Democratic Republic, as East Germany was known] history. . . .

“It’s not in the lesson plans of the school. And in the west, they seem to know less. Sometimes they ask questions that seem silly to me, like, ‘Did you have toilet paper?’ They’re my age, and they know less. I realize how close it was to me, and how far it was from them. . . .

“When the wall came down, the whole east was changed. All the factories that didn’t work were closed. A lot of people had to reorganize their lives, just like my parents. Every time you go to a museum, there’s always this aspect, about how when the wall came down, everything changed.”

It is mostly through his parents and their former East Berlin friends that Valentin has developed his sense of what the city was like before he was born and how lucky he is to be living now.

“From my father I hear about what it was like in the army and how easy I have it now, that I don’t have to go into it. When my father thinks I’m doing something he could never have done, he has a story about it or he tells me how much he appreciates how different it is now. . . .

When he was 16, Valentin spent a year in the U.S., living with a family outside Denver, an impossibility for students of his father’s era.

“It was very positive for me to have this experience. . . . It was a different mentality.

“The family was very different. It was very American. I don’t have any sisters or brothers, but they had three kids and all lived together. The family was chaotic and I wasn’t used to that much chaos, but after one month, I really liked it.

“And maybe because I was raised by parents who grew up in the DDR, the whole capitalist-consumerist thing wasn’t so important for me. . . . So it was completely different from me but always very exciting. Even the bad stuff was still exciting.”

Freedom of movement and other rights feel like second nature to Valentin, a far cry from the heavily circumscribed world the older generation in the east grew up in.

“For me, travel is something normal. My family has done a lot because they hadn’t had the freedom before. I can’t imagine how it would be where you would only have three or four countries in the east that you could travel to. . . . [For] people my age, in my class, it’s normal.

“Sometimes we even smile at these stories from our parents because it seems so far away and so unrealistic, and even absurd.”

He’s happy to be living in Berlin as a unified city and Germany as a unified country, but as his parents’ son, Valentin has inherited some of their east-bred values and attitudes, which means that the west holds less appeal.

“It might be different, but I could imagine living there. It’s not so weird to me. . . . But I think the east might be more comforting to me, would feel more like home, with stuff I’m used to, or with people I can better understand or have a closer mentality to mine.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.