Thailand’s King Bhumibol, world’s longest-reigning monarch, dies at 88

King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand, the world’s longest-reigning current monarch who was embraced as a near-deity by his subjects, died Thursday. He was 88.

The palace said the king died at Bangkok’s Siriraj Hospital, but it did not give a cause or additional details. The king had withdrawn from public life over the last decade and lived at a Bangkok hospital due to his ill health.

His death threatens to fling the fractured country into deeper political upheaval. The military junta that took power two years ago promising order continues to cement its hold. And unlike his father, the king’s chosen successor, Crown Prince Maha Vajiralongkorn, is deeply unpopular in Thailand.

In an age when monarchies have fallen from favor in many countries, Thailand’s American-born, Swiss-educated king was a striking exception. Although he had few clearly defined powers, the authority and respect he commanded were without parallel in Southeast Asia.

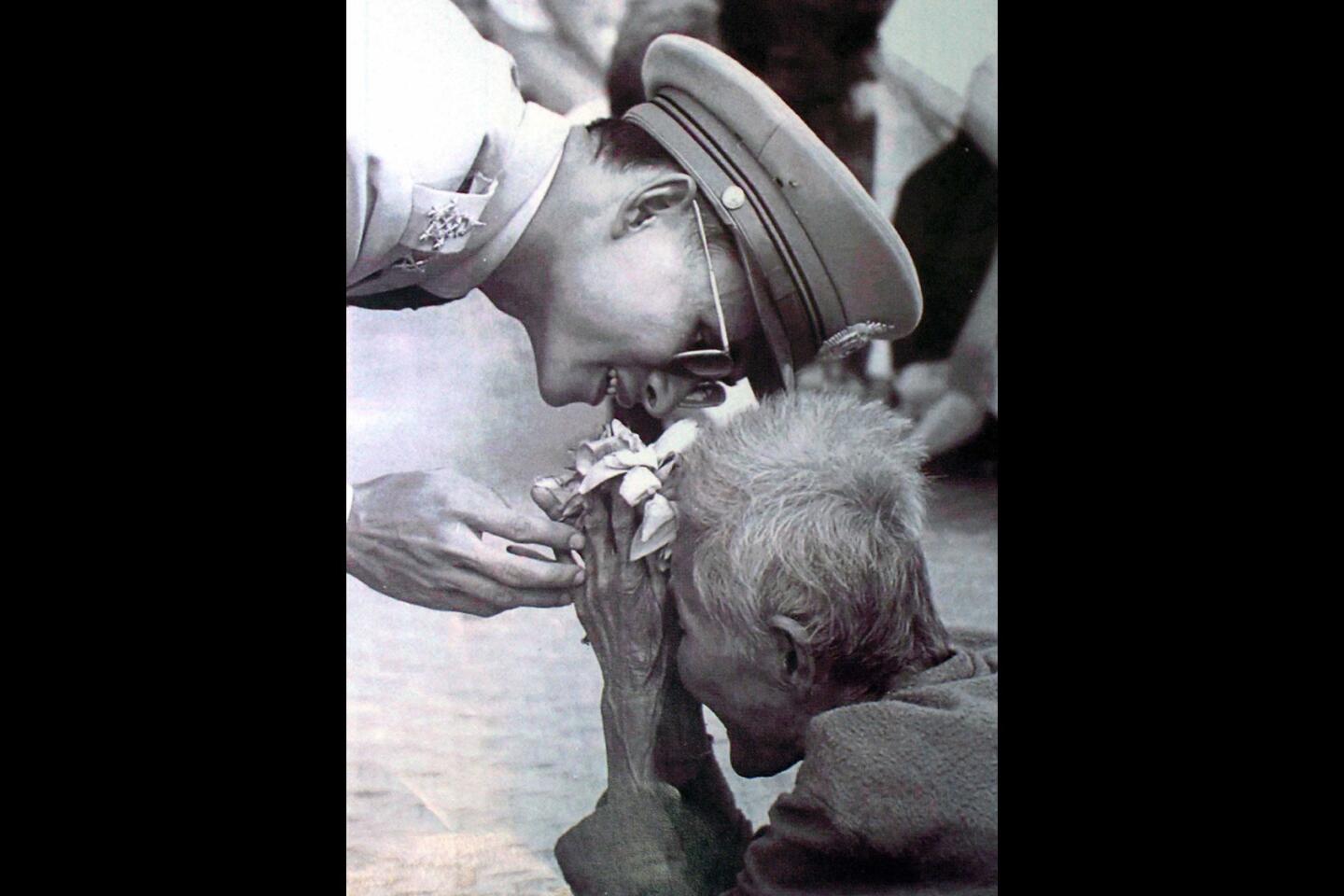

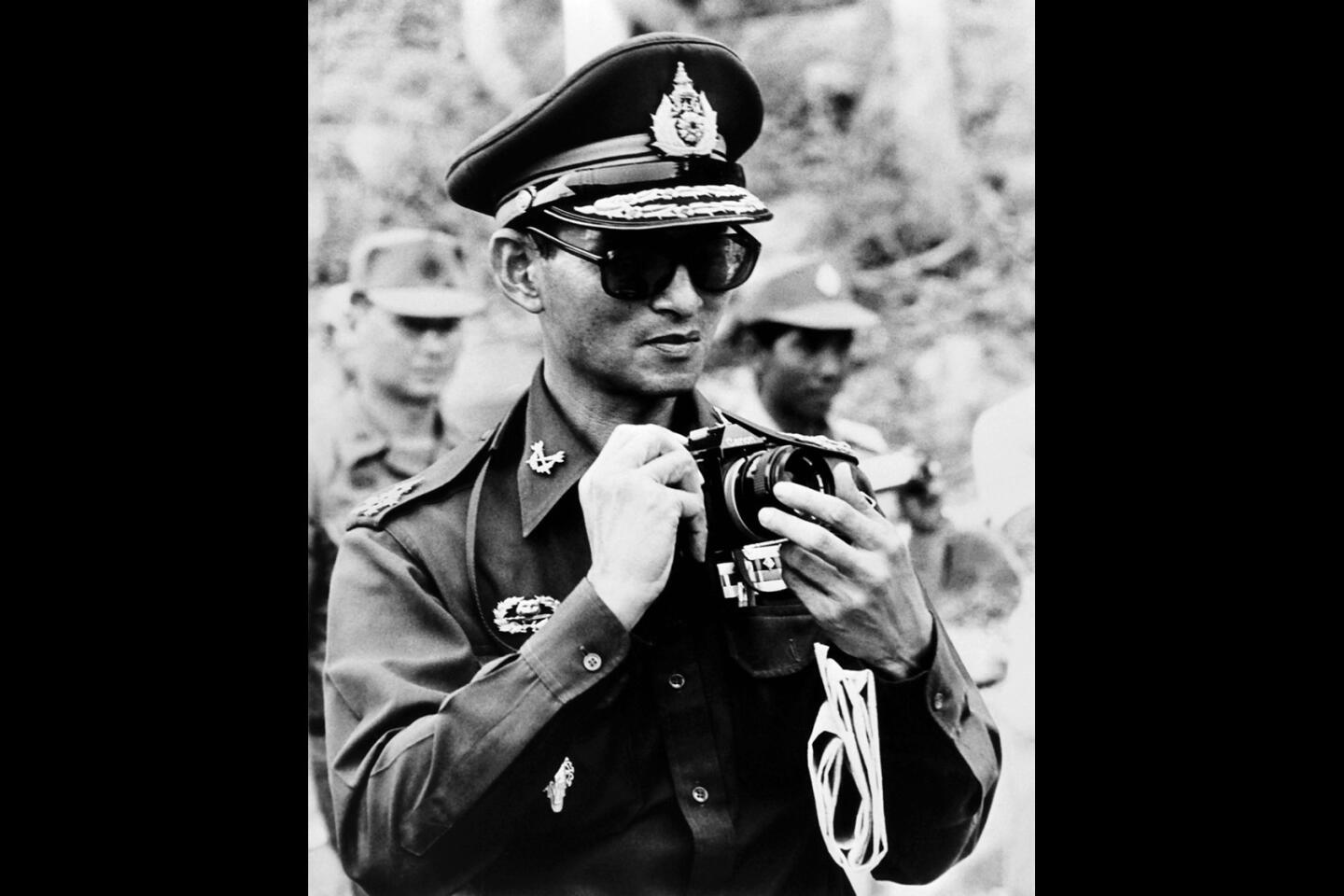

A trim, bespectacled man who resided in opulent palaces yet lived relatively austerely, King Bhumibol knew that his great strength was that he had earned his authority rather than assuming it as a birthright. He never lost touch with his people, be they rich or poor, and was often seen trudging off, a camera around his neck, to examine rural development projects.

Not widely known outside Thailand, the king was an accomplished composer and musician who had jammed with Benny Goodman and Lionel Hampton. As an adult, he virtually never left Thailand — ”We felt more secure knowing he was here,” one Thai said — and devoted most of his energies to improving the lot of the poor. His death cast a pall of sorrow over the nation. Even as his health faltered in recent days, Thai stocks fell sharply and well-wishers gathered outside the hospital where he was being treated.

Bhumibol was born Dec. 5, 1927, in Cambridge, Mass., where his father was studying medicine at Harvard. His mother, a Thai commoner, was studying nursing. A descendant of a 700-year-old dynasty, the king was the great-grandson of King Mongkut, who was depicted in Rodgers and Hammerstein’s musical “The King and I.”

Only through a series of tragedies did Thailand get Bhumibol — who was never in line for the crown — as its king. In 1936, four years after a bloodless coup had limited the powers of the monarchy, King Prajadhipok abdicated without an heir. The crown passed to the king’s nephew — Bhumibol’s older brother, 10-year-old Prince Anand. A regent was installed while both boys went to Switzerland to finish their schooling.

Anand went on to become king. But on June 9, 1946, at the age of only 20, he was found with a bullet through his head in his Bangkok palace. The death was never explained. Bhumibol, still a teenager, took the crown of a monarchy that was self-destructing and controlled by the military.

“When I opened my mouth, they [the generals] would say, ‘Your Majesty, you don’t know anything,’” the king once recalled. “So I shut my mouth. I know things, but I shut my mouth.”

Rather than accept a role as a do-nothing king, he became active in village technology. He toured the country, overseeing rural development projects. By the time of his death, more than 2,000 projects in Thailand bore the imprint of his planning.

Behind the scenes, he wielded great influence. Politicians and generals sought his advice, and virtually all Thais considered his every utterance tantamount to a royal decree. He was the only Thai who could end bloodshed in the streets or foil a coup with just a word.

In May 1992, when soldiers killed dozens of pro-democracy demonstrators in Bangkok, the king summoned the student protest leader and the prime minister (who was a general) to the palace for a televised dressing-down. Both approached the king on hands and knees.

“Should the confrontation be prolonged, the country could be wrecked,” he told them. The violence stopped and the prime minister resigned in disgrace.

Under the king, Thailand grew from a quiet rural land in the 1950s into one of the 1990s’ “economic tigers” of Southeast Asia. Poverty was reduced, millions of Thais moved into the middle class, and Bangkok became a dynamic trading and banking city, with showcase high-rises and luxury hotels. Thailand’s press was free and its society was one of the most open in Asia.

But, however great the king’s achievements, he left behind a troubled country. The Asian economic crisis of 1997 hit Thailand especially hard, forcing the government to turn to the International Monetary Fund for help. AIDS was epidemic, the gap between rich and poor immense, and urban growth largely uncontrolled.

Still, Thailand cemented its position as one of the richest countries in Southeast Asia, even as it was rocked by political turmoil.

A military junta seized power after years of demonstrations and clashes between two factions, known by the color of their shirts. The red shirts, often farmers and rural poor, backed the return of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who was ousted in a coup in 2006.

When his younger sister, Yingluck Shinawatra, took office years later she tried to pass an amnesty bill that would allow for his return. The yellow shirts, generally elites and urban middle-class Thais, decried the move. Violent clashes underscored the country’s severe economic inequality and worries of rampant corruption in the democratically elected government.

The junta held a national referendum in August on a proposed constitution, but banned opponents from campaigning against it and prohibited election monitors. The measure makes it more difficult for any one politician or party to gain power, a move the junta says will prevent corruption, but which its opponents fear will threaten democracy.

Vajiralongkorn, the 64-year-old crown prince, will inherit a sharply divided country.

Bhumibol was king for more than 70 years. Queen Elizabeth II has sat on the British throne for 64 years.

Staff writer Jessica Meyers and the Associated Press contributed to this report.

MORE OBITUARIES

Shimon Peres, Israeli leader instrumental in peace process, dies at 93

Nobel-winning playwright Dario Fo dies at 90; mocked Italian politics and religion

Dr. J. Thomas Ungerleider, early medical marijuana researcher, dies at 85

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.