His students beat him to death during the Cultural Revolution. The school called it a suicide

- Share via

Reporting from BEIJING — For half a century, Cheng Zhangong has mourned his father’s passing but didn’t want to dwell on how he really died — at the hands of Cheng’s high school classmates.

To this day, Cheng still remembers finding his father, a high school vice principal, slumped over a sandbox steps away from his old office after being beaten with long sticks by his own students. “Almost overnight they turned against my father,” said Cheng, 69, whose dry eyes belied pain. “I understand they were under the influence of the political system.”

The purges that defined the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution began 50 years ago, in August 1966. Youth mobs, buoyed by idolatry for Mao Tse-tung, threw themselves into a crazed campaign as Red Guards. In colleges and high schools throughout the country, they repudiated their teachers and principals as “capitalists” or “stinking intellectuals” and pressed them into service as laborers.

On one oppressively hot day in the month that the purges began, Cheng’s father was made to sweep the school grounds for hours without being allowed a sip of water. When he paused to rest, he took a beating from the Red Guards. When Cheng intervened, his classmates kicked him and chased him away.

The next morning his father collapsed into a coma after predawn cleaning duties and died. By the time the dark decade ended in 1976, more than 1.7 million others would have perished.

“For many years, my family didn’t dare talk about this,” said Cheng, who couldn’t bear to set foot on his high school campus, a few blocks from his home, let alone to broach the subject of his father’s beating.

Not until a few years ago, when he chanced upon a website that said his father had committed suicide out of guilt. Under the name of the “Chinese Holocaust Memorial,” the site keeps a running list of victims of the purges in the academe.

Determined to set the record straight, Cheng reached out to Wang Youqin, the Chicago-based Chinese academic who founded the site.

Wang was the daughter of two college instructors in Beijing during the Cultural Revolution and became a “sent-down youth” — one of the millions of urban, educated teenagers who were exiled to far-flung regions to live and work with peasants during the Cultural Revolution. In 1966, Wang, then 13, and her sister were sent to the border with Burma to clear wooded areas; her left palm still bears a scar from a pickax.

When she returned to Beijing 13 years later, in 1979, to enroll at Peking University, Wang learned that several of her high school teachers, and a few professors from her university, had died. She set out to learn more about the circumstances of their deaths, each of which was officially deemed a suicide.

She discovered that the classroom where she used to attend lectures over the chirpings of passing sparrows had been awash with the blood of a Russian-language lecturer, who slit his wrist with a razor to end the pain of persecution. By day, he was subjected to humiliating “struggle sessions.” By night, he was corralled with a dozen other faculty members into the classroom, where they slept on dirt floors covered with loose straw. Only by tracking down the faculty member who had slept next to this instructor did Wang learn how he had taken his life.

Among the first to perish in the purges was Wang’s high school principal, Bian Zhongyun. She was pummeled with baseball bats and table legs and scalded with boiling water. Even as she lay unconscious on the steps outside a dormitory building, some students kicked her, accusing her of playing dead. By the time she was transported to the hospital, her body was already in rigor mortis. Wang learned all this from Bian’s husband, who saved Bian’s blood-soaked clothes.

Over the years, Wang has expanded her inquiry to include several hundred more educators targeted during the Cultural Revolution. In the late 1990s, while teaching Chinese at Stanford University and publishing her interviews with victims’ families, Wang said, she was stalked by former Red Guards threatening to harm her. She didn’t relent, but relocated to Chicago to take up a teaching job. In 2000, Wang launched the website and listed about 800 dead for whom she has names and family testimony, or any shred of information she had managed to glean. Every week she’d receive emails or letters from victims’ families — until the Chinese government blocked the site a year later. In 2004, she published a book in Hong Kong detailing the deaths.

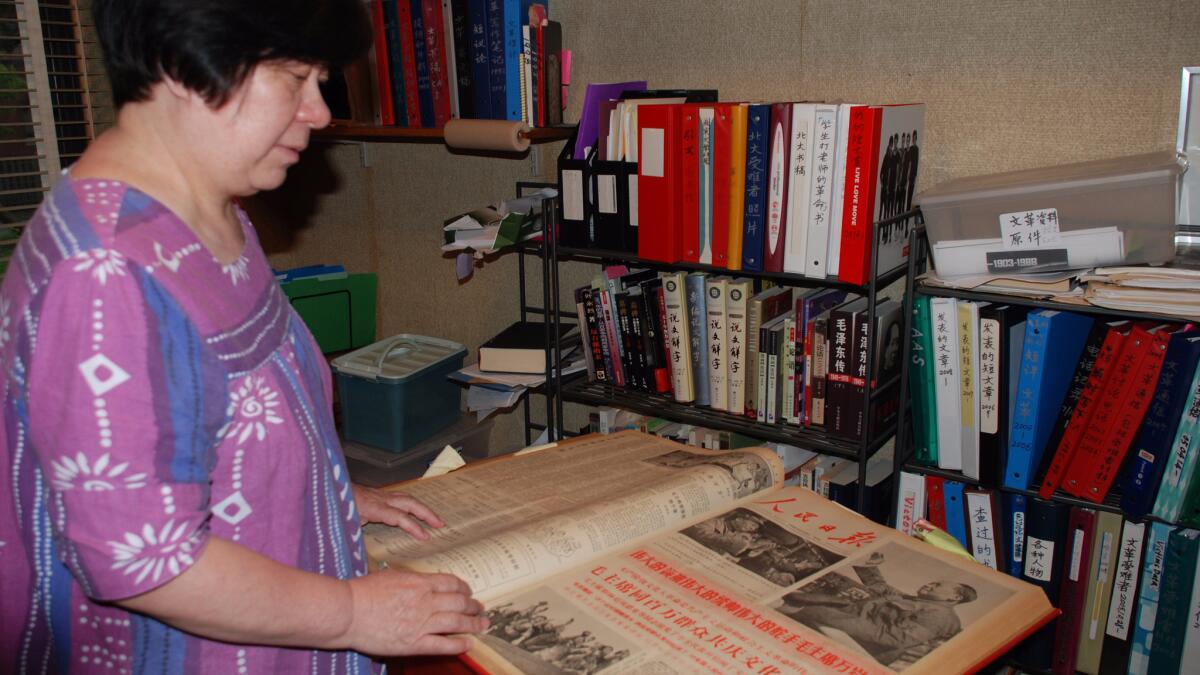

And over the last decade, her three-bedroom condo on the campus of the University of Chicago has morphed into a full-blown repository. Neatly labeled binders of interview notes were shelved above bound volumes of fraying pages of People’s Daily from the 1960s. Every summer, Wang travels back to Beijing to teach Mandarin while continuing to seek details of the deaths. So far, she has conducted more than 1,000 interviews with family members of the victims.

Her persistence has pierced the official silence enforced by the Chinese government. As time goes on, the families of those who died are more willing to open up.

Cheng, for one, sent Wang a six-page witness account detailing his father’s demise down to his last breath. She previously had only the school’s official history to go by.

“A number of cases have emerged with more details and clarity because more family members of the victims have come forward,” said Wang. “While I can’t change anything, what I can do is to record the facts about the victims. Because for so long they’ve been absent from official history, the Cultural Revolution has been sanitized into a political event and rendered as victimless.”

Two years ago, one of Wang’s schoolmates and the daughter of one of communist China’s founding generals, Song Binbin, apologized for her role in Bian’s beating death. But so far, she has proved to be the exception.

Even at the half-century mark, the central government has yet to give a public account of what happened. And the only museum that commemorates the victims, founded by retired local officials in a small southern Chinese town a three-hour drive from Hong Kong, has over the last few months been cloaked with banners of Communist Party slogans — apparently on government orders, according to media reports.

“Why did it become such a taboo even 50 years later?” Wang asked. “It were as though, if we never talked about it, then it never happened. Who is the Chinese government kidding?”

Roderick MacFarquhar, a Harvard historian who has written extensively about the revolution, said absent any official account or public acknowledgement of their loss, the victims’ families can find some solace only in Wang’s efforts.

“This is a way to memorialize the victims,” said MacFarquhar. “The families want justice, and some kind of recognition of the tragedy.”

Even though the Cultural Revolution raged all over, the region of Guangxi, on the country’s southern border, saw the heaviest death tolls — 86,000 to 150,000 by some estimate — and is unique in having internal official accounts about what transpired there.

A historian at the library of Cal State Los Angeles, Song Yongyi, recently published those accounts online — all 7 million characters detailing county-by-county killings. Since the 1990s, he has been building a database on the Cultural Revolution by compiling any material he could find. In 1999, he was detained for five months in China on allegations of stealing state secrets. But he remains undaunted.

“What I want to do is to restore to the people in the People’s Republic the right to know,” he said.

Revealed in his recently published documents is a hilltop burial ground, a rare resting place for the Cultural Revolution dead that still exists. More than a dozen unmarked graves lie scattered across this partially cleared outcrop, which at the time was a cattle farm supplying a nearby high school.

Shielded by eucalyptus trees and waist-deep cogon grass, each grave is a dune-shaped pile of crushed rocks and caked mud about 3 feet tall. Nearly all are without a tombstone or any marker, and appear unattended. Locals said rice paddies have fallen fallow to make way for roads. The clanging of a lone earthmover echoed in the air.

There is little doubt that these last physical markers of the Cultural Revolution dead will soon be flattened — and forgotten.

Law is a special correspondent.

ALSO

What it was like to be a foreign exchange student in Beijing at the end of the Cultural Revolution

China’s censors are cracking down on the online news industry

Before the computer, there was something almost as complex: the Chinese typewriter

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.