China says it built a railway in Africa out of altruism, but it’s more strategic than that

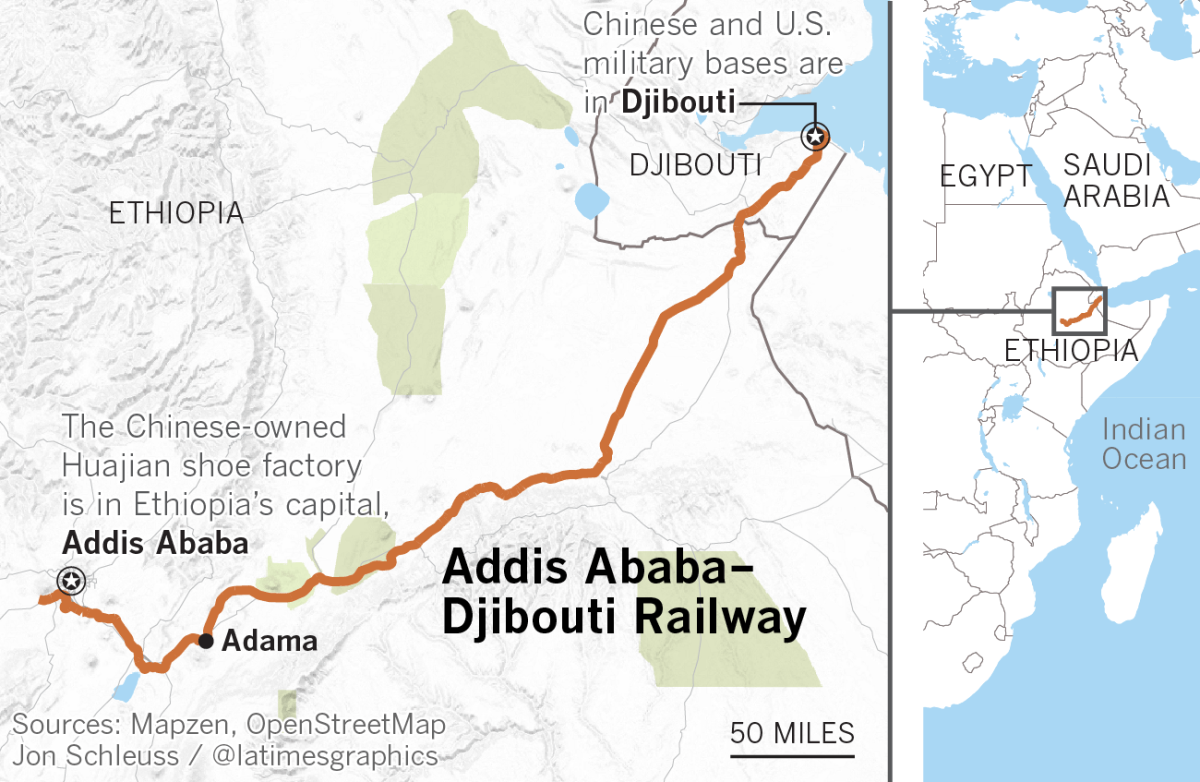

Africa’s past is the mildewed train station in central Addis Ababa, where locomotives sit gutted and rusted tracks vanish in the grass. The line was once the greatest in Africa; built by France in the 1910s, it ran more than 450 miles northeast to neighboring Djibouti, where the desert meets the sea.

Africa’s future is the new station a short drive away, a yellow-and-white edifice with grand pilasters, arched windows and a broad flagstone square. It’s connected to a $4-billion, 470-mile-long rail line, the first electrified cross-border rail system in Africa.

The new rail network was built by China’s state-owned rail and construction firms, which were eager to promote their investment in Africa’s future. Red banners running down the towering facade of the new train station declare, in bold Chinese characters, “Long live Sino-African friendship.”

China has described its railroad adventures in Africa as an exercise in altruism.

Yet for China, investing in Ethiopia — one of the world’s poorest countries — is more strategic than philanthropic. With U.S. engagement on the continent at a low ebb, economically and politically, China sees an opportunity to improve transportation through the Horn of Africa and make itself the dominant economic partner on a continent that is about to see an explosion of new cheap labor, cellphone users and urban consumers.

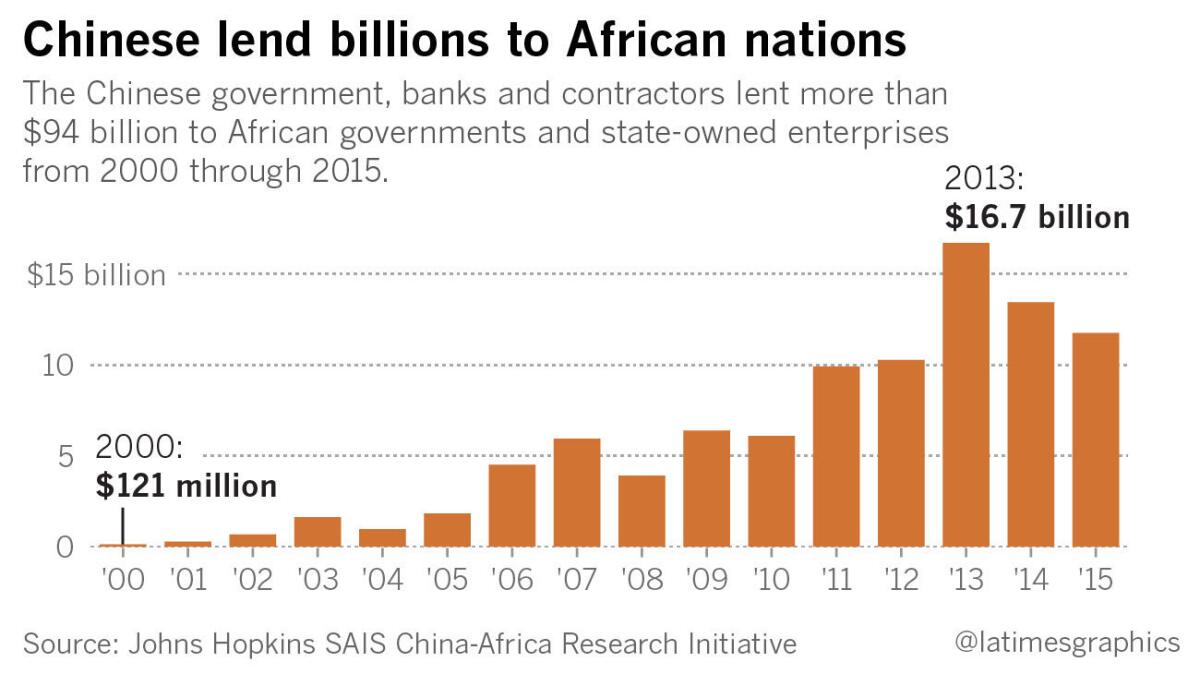

For several decades, China’s African investments were aimed primarily at creating political allies across the continent. Beijing invested heavily in hearts-and-minds projects such as soccer stadiums and hospitals. But a significant change is underway. China now sees Africa as an important economic opportunity. It has been pouring money into infrastructure across the continent, and this week it opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti.

By 2034, Africa is expected to have 1.1 billion workers, the world’s largest working-age population, according to economic forecasts. By 2025, the continent’s consumers will be spending $2 trillion a year.

“My vision is, by 2020, Ethiopia’s economy will be among the world’s mid-level economies,” said Mekonnen Getachew, a project manager at the Ethiopian Railways Corp., which oversees the rail line. “The rail will make every economic activity easier. Our economy will boom.… This railway is making Ethiopia great again!”

The Chinese march through Africa has come as U.S. engagement on the continent has been dialed down to its lowest level in years.

President Trump has barely mentioned Africa in his public statements, and his “America first” rhetoric, some Africa experts say, is pushing the continent further into China’s embrace.

While Chinese companies have looked to make money in Africa and share with Africans some of the jobs, tax revenues, infrastructure and spinoff development that go along with new investment, the U.S. has focused on improving African lives through aid, social programs and conditional loans.

Western companies have often been reluctant to participate in African infrastructure projects for fear of overwhelming maintenance costs. In many cases, they could simply build new projects more cheaply.

“Americans still see Africa as a place where there are a lot of presidents for life, wars and famines,” said Reuben Brigety, dean at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs and a former U.S. ambassador to the

In Ethiopia, the country’s rail executives said China seems more attuned to Africa’s needs.

“China doesn’t give simple aid,” Getachew said. “They do give loans. You work, and you return back. That’s a good policy. Aid is just making slavery.”

For decades, the China-Africa relationship was almost entirely transactional: China gave African states easy loans, enabling them to build bridges and stadiums; in return, those states gave China access to natural resources, such as oil, timber and nickel, fueling China’s economic boom.

But as China's foreign policy grows more sophisticated — and more ambitious — that era is ending, and the relationship is growing much deeper, with extraordinary implications for the continent’s future.

Chinese nationals in Africa — once a scattered cohort of officials, mining executives and construction crews — are being joined by tourists, peacekeepers, poachers, soldiers and small-time entrepreneurs. Together, they are generating both riches and new political clout for Beijing and helping establish China as the world’s newest superpower.

For Ethiopia, China’s infrastructure expenditures are an essential element in plans to emerge from a long cycle of drought, poverty, famine and war. The railroad is a start.

Ethiopian officials say the line will eventually grow into a 3,000-mile rail network that stretches across neighboring Sudan, South Sudan, and Kenya — where China recently completed another railway, for $3.8 billion.

The new Ethiopia-Djibouti line’s trains are near-identical copies of the carriages that traversed China before the government, about a decade ago, began swapping them out for high-speed rail. They have the same ramrod-straight seat backs; the same boiling water dispensers in nearly every car, essential for instant noodles and green tea.

Ethiopia relies on Djibouti’s ports for 90% of its foreign trade. But since the old railroad collapsed in 2009 after decades of decline, the landlocked country’s billions of dollars of imports and exports — fuel, coffee, livestock — have had to travel by truck, a three-to-four-day journey along rutted, dusty roads.

The new rail line, which will be fully operational by October, will cut the trip to 12 hours.

“The coaches are very new. It’s electric. It’s very comfortable. You enjoy the scenery along the corridor,” said Yehualaeshet Jemere, a top official with the Ethiopian Railways Corp. “It’s like a dream come true for us.”

Here in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s capital, China is driving an urban renaissance. It has built whole neighborhoods, a $475-million light-railway system and even the African Union headquarters, a $200-million complex that dominates the city’s skyline. In the country’s hinterlands, it has constructed several industrial parks, anticipating a manufacturing boom.

Beijing’s first overseas military base had its official opening on Tuesday near the terminus of the new rail line in Djibouti. The 90-acre complex includes housing for thousands of soldiers and berths for commercial and military vessels.

But Beijing’s reach already stretches well beyond Djibouti and Ethiopia. China surpassed the U.S. as Africa’s largest trading partner in 2009, and the numbers continue to climb. (Foreign direct investment has dropped in recent years, along with declining global resource prices.)

China stands to gain tremendously from its investments. Chinese businesses, hampered by slowing growth at home, are increasingly treating the continent as a major overseas market.

In Beijing, the political will driving such projects extends to the top. Through the “Belt and Road Initiative,” launched by President

“Today’s Africa is a continent of encouraging and dynamic development,” he said in a speech. “Such a momentum of independent development is unstoppable.”

In a Chinese-built industrial park along the new rail line, in a Chinese-run factory, thousands of employees of Huajian Shoe Co. — all of them Ethiopian — work 13-hour days gluing, inspecting and boxing women’s shoes. Above them hang propaganda posters in Chinese, English and Amharic, Ethiopia’s national language, imploring workers to “win honor for the country” and to “absolutely obey.”

Zhang Huarong, the company’s chief executive, wandered through the immaculate rows of workers on an inspection tour, a crowd of subordinates trailing behind him. “Africa is too poor,” he said. “It needs entrepreneurs like me to balance out the global economy, so that more people can live a happy life.”

Zhang was proud of his Ethiopian investments. The new rail will knock shipping prices from $5,000 per container to $3,000, he said. And for the cost of one Chinese worker, Zhang can hire five Ethiopians. He plans to employ 50,000 within eight years.

“Ethiopia is like China was 40 years ago,” he said. “Even though this place is pretty tough, we think within five or 10 years, its economic development will be pretty good.”

Every pair of shoes produced in Huajian’s factories, in China and Ethiopia, is exported to the U.S.; its clients include the labels Tommy Hilfiger, Guess and Lucky.

As the sun set at the factory, about a dozen Ethiopian workers lined up in formation, closing out the workday. An Ethiopian manager waved his arms, as if conducting a choir, and together they sang a Chinese military anthem from the 1950s.

“Unity is strength. Unity is strength,” they sang in Mandarin. “Open fire on the fascists. Bring death to all nondemocratic systems.”

Adama, a city of 300,000 people 60 miles down the rail line from Addis Ababa, is preparing for a boom — but not everyone considers it progress.

Small blue auto rickshaws jostle for road space with hulking Chinese trucks, and rows of half-built concrete houses stretch up into the plains. At the end of a half-built road is the city’s new train station — another massive edifice, its interior covered in dust.

Since construction began six years ago, the price of land in Adama has increased sevenfold to about $140 per square foot, said Shambel Worku, the station’s manager.

Yet progress is slow, and locals are suffering, highlighting the hidden costs of rapid economic development. In late January, the road was still a mess of pylons and ditches. And the machine-gun-toting security guards overseeing the empty station lacked water, forcing them to walk hours for a drink.

Farmers in Lugo Village, an impoverished cluster of slapdash houses a few hundred yards from the station, said the rail project has made life unbearable, in part because locals can’t cross the rail construction zone, but must go around it.

It “divides the village into two,” said Tashoma Kafani, 72. Before construction began, he said, he could walk to his barley and maize fields in about two hours; now, he needs about five.

“We have repeatedly contacted the local authorities,” he said. “We have been expressing our problems and voicing our concern about the absence of a bridge. But so far, they haven't been responsive.”

As for the Chinese planners who designed the project, Kafani can’t even imagine how to communicate with them.

The rail line crosses into Djibouti about 360 miles to the northeast. It ends in the capital, Djibouti City, where, on the western edge of its main port, China is building the new military base — an unprecedented projection of power for China’s rapidly expanding army.

Djibouti is a former French colony of 850,000 people, and its capital — a patchy grid of dusty streets and sun-bleached Moorish buildings — feels like an island, hemmed in by endless miles of massive, walled-off foreign compounds.

China’s base is about eight miles from Camp Lemonnier, America’s only full-scale base in Africa. France, Germany, Italy and Japan also maintain bases in Djibouti, both for its political stability — its president, Ismail Omar Guelleh, has ruled the country since 1999 — and its proximity to terrorism hot spots in Africa and the Middle East.

Chinese officials call the base a “supply center,” intended primarily to support China’s anti-piracy efforts in the Gulf of Aden — a crucial shipping route — and protect its commercial interests.

“People are very sensitive about [the Djibouti base], but I don’t think that’s fair,” said Xu Guangyu, a retired People’s Liberation Army major general in Beijing. The U.S. maintains hundreds of overseas bases, he said. “We in China think it’s silly, to have so many overseas military bases. We have built only one supply center. So why all the speculation about this news?”

Peter Dutton, professor of strategic studies at the Naval War College in Rhode Island, said China’s new base says more about the country’s economic heft than its military ambitions. “What we’re talking about is fundamentally geoeconomics, rather than geo-strategy,” he said.

On the other hand, China is “walking away from some of the premises that have undergirded its foreign policy for 60 years,” he said. “They’re beginning to act like a great power which takes a role in international politics and security. And that’s a fairly significant change for China.”

China has given Djibouti’s government billions of dollars in loans and investment, helping fund new ports, two airports and a pipeline for drinking water from Ethiopia. It’s also planning a series of power plants and a tax-free manufacturing zone. Nearly a quarter of Djibouti’s population lives beneath the poverty line — its unemployment rate in 2014 was 60% — and locals say the country desperately needs the help.

Djibouti inaugurated the rail line in January in a mass celebration featuring Djiboutian celebrities and African heads of state. By early February, the line hadn’t yet opened, and the festive atmosphere had died down, but locals were feeling hopeful nonetheless.

At the rail line’s penultimate station — another empty monolith — Degan Mohamed, 31, stood alone but for five security guards, sweeping up dust. She was hired as a janitor in October, her first-ever job.

“I had no alternative,” she said. “I am earning money, so I am quite happy.”

ABOUT THIS SERIES:

This is the first in a series of reports on a massive program of Chinese investment that is reshaping Africa. Times staff writer Jonathan Kaiman and visual journalist Noah Fowler traveled to Ethiopia, Djibouti, Kenya and Ghana with support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. More online, including 360-degree videos, at latimes.com/chinainafrica

For more news from Asia, follow @JRKaiman on Twitter

ALSO

The neat-as-a-pin African country where people are executed for petty theft

Armed only with her grandmother's shotgun, a South African woman fights to save her rhinos

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.