From the Archives: Hell’s Echo: The Jonestown Mass Suicide

Editor’s note: Nov. 18 marks the 30th anniversary of the Jonestown tragedy in which 913 people died in a ritual of mass suicide and murder at a cult compound in Guyana. This story was first published on the 25th anniversary of the massacre.

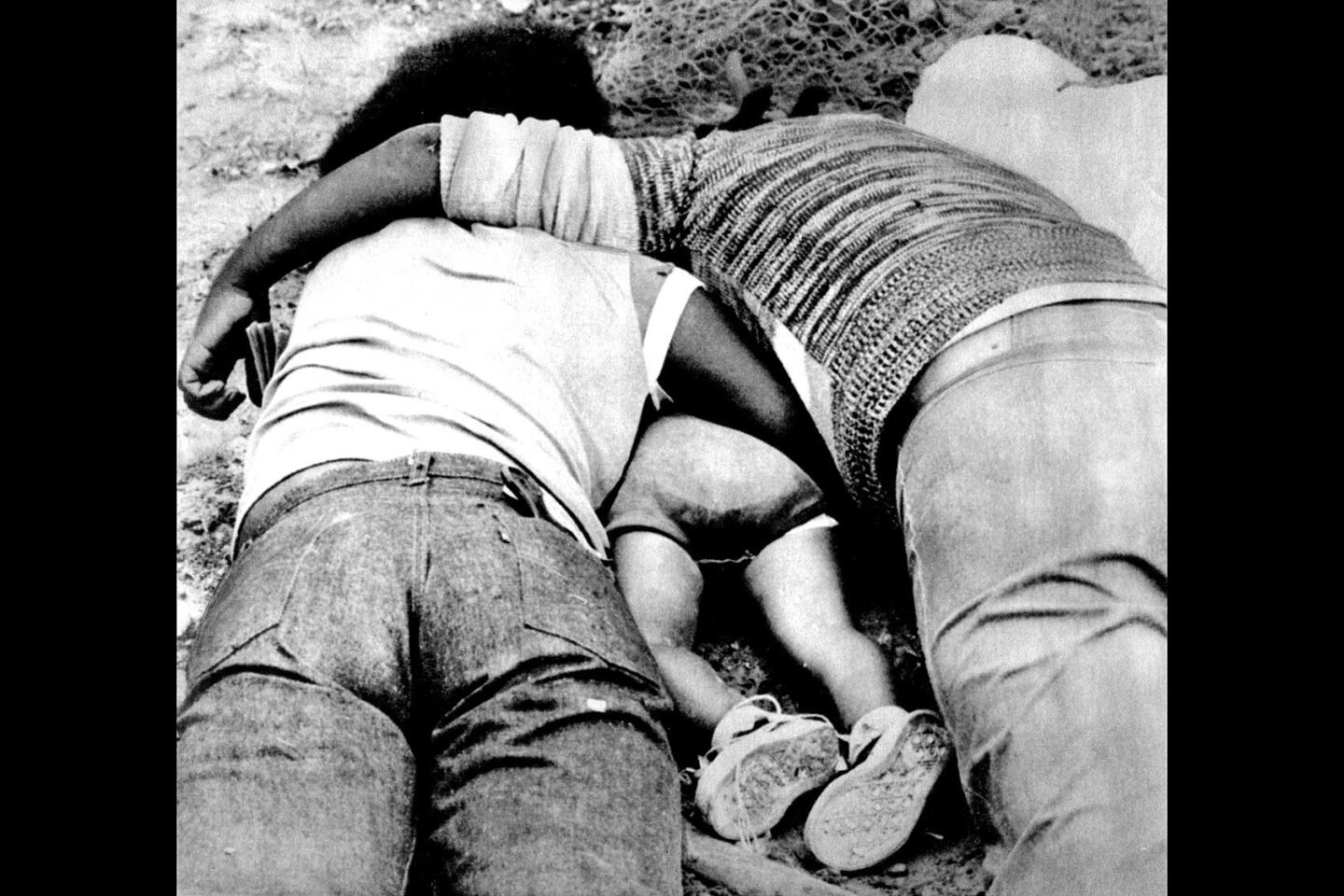

OAKLAND -- On a grassy slope in Oakland, more than 400 take their final rest, mostly children who were unclaimed or unidentified.

And across San Francisco Bay, a U.S. congressman is buried in a national cemetery not far from a park that bears his name.

Their lives converged 25 years ago Tuesday in a South American jungle clearing that has come to symbolize the worst that organized religion, cults and madness can reap.

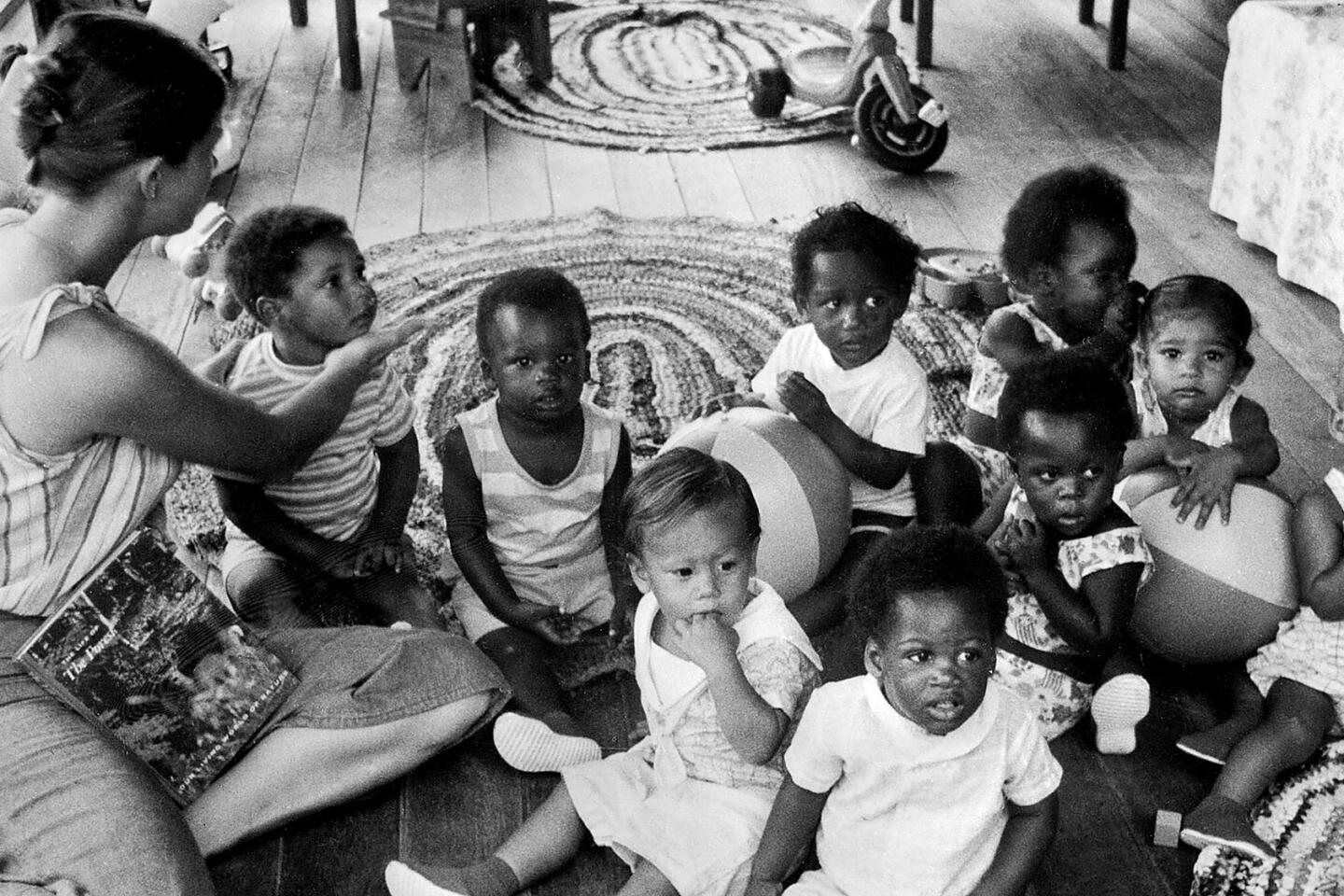

“The people of Jonestown were a precious people, family people,” the Rev. Jynona Norwood, who lost 27 relatives, told mourners in Oakland. “It is an injustice when people say they were unintelligent.... They had a natural desire for a better life for themselves and their children.”

Jungle reclaimed Jonestown years ago. But even now I can see them together in the open-air pavilion there -- Rep. Leo Ryan (D-San Mateo) on stage, microphone in hand, addressing a rainbow of Peoples Temple members from the heartland, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Taking their cues from the Rev. Jim Jones, they applauded Ryan on the opening night of his mission to find whether the settlement was the brutal work camp described by escapees or the utopia extolled by supporters.

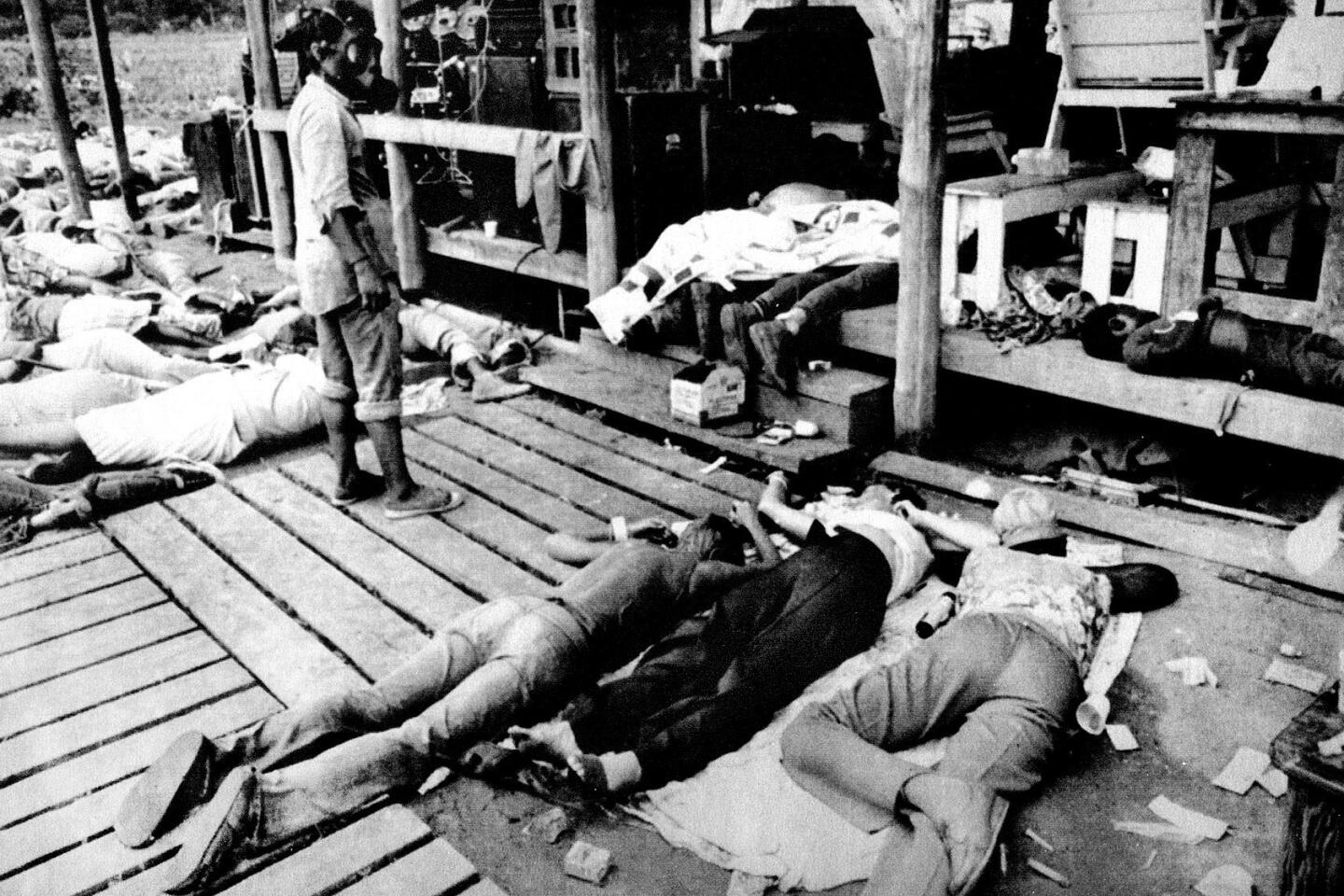

Within 24 hours, virtually all would be dead. Ryan was shot to death on a nearby airstrip, along with a church defector and three of my fellow newsmen. Then the temple members were killed at the pavilion in a ritual of mass suicide and murder. The final toll: 913.

“We need to remember to remember,” Norwood said. “If you can say 1,000 people died and it can easily fall from your lips, you are remembering to forget.”

Lost in the sea of books, films, studies and investigations that engulfed Jonestown over the past quarter-century are two simple truths that took me years to fully comprehend. Jones’ followers were ordinary people who joined the temple for the best of motives and were betrayed.

And Jones, beneath the sheen of a dashing, raven-haired preacher, was profoundly disturbed for much of his life. His underlying sickness poisoned his life’s work and put him on a collision course with those he called his enemies, including me.

“He was a sick, frightened, heartbroken man,” said his son Stephan in an interview. “And out of that came this need, or desire, to control every part of his life.”

Jones had identified with the underdogs and the oppressed since his Indiana childhood, where he felt the pain of parental neglect and adopted churches as his extended family.

But the seeds of his madness took root there too. At an early age, he conducted cruel experiments on barnyard animals and tried to control his playmates, locking them up in a barn and later threatening his best friend with a gun. These tendencies to control and manipulate people were marks of his adulthood, along with a creeping paranoia, drug abuse and a repertoire of faked attacks on himself.

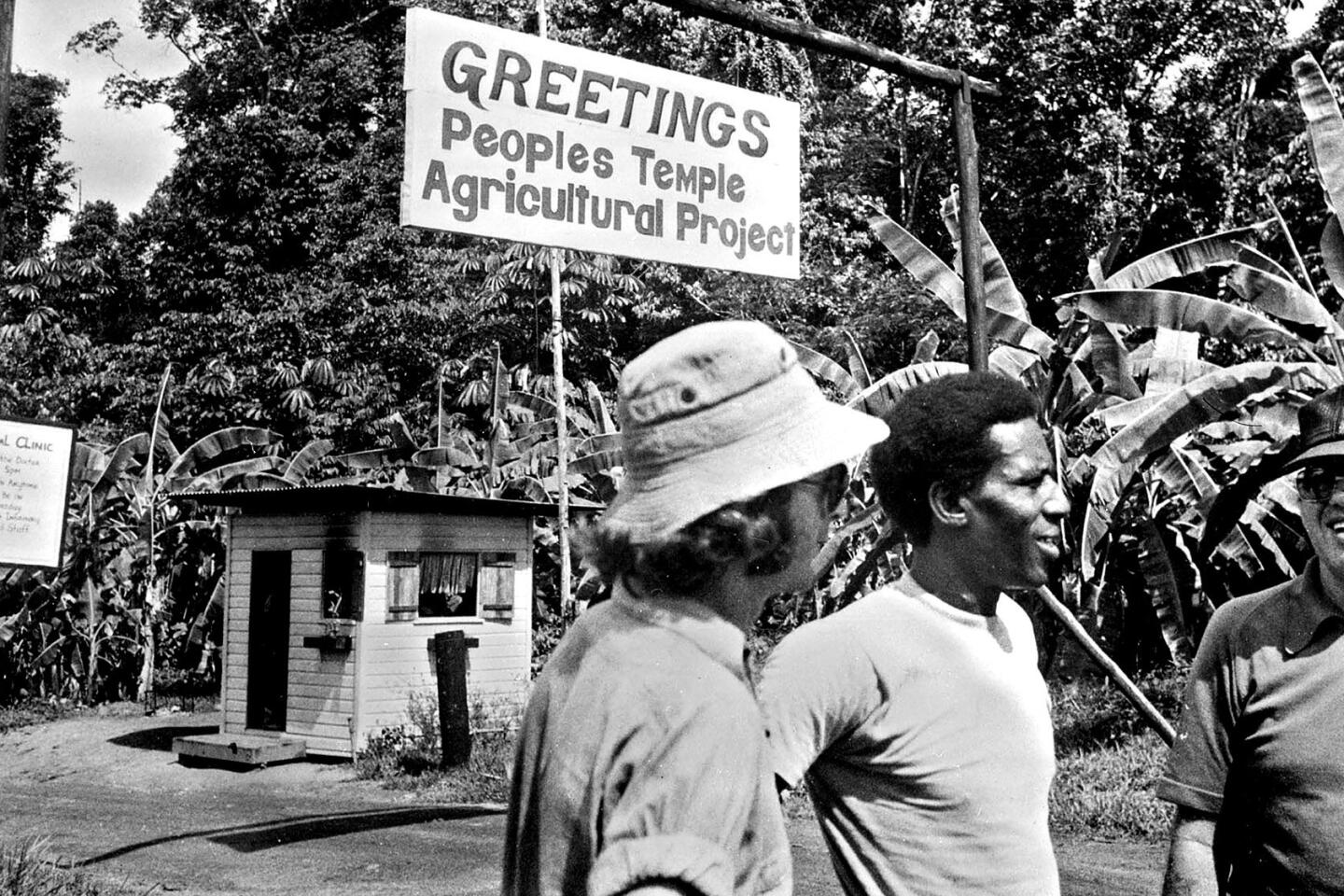

But he kept them hidden from most of his congregants and outsiders as he built his church in Indianapolis and joined the Disciples of Christ denomination. Peoples Temple was a model of racial integration and social action even before he moved the temple to California, where he established his credentials as a humanitarian civic leader who ran food programs and helped elect San Francisco Mayor George Moscone and other liberal Democrats in the mid-1970s.

My first exposure to the people of the temple came in 1977, when a handful of defectors agreed to meet me and another San Francisco Examiner reporter at a house in the Haight-Ashbury district. They seemed remarkably normal and idealistic, with dreams of a world free of racism and better lives for themselves and their children. They had jobs. Some were college-educated.

But they described a closed universe where families were systematically divided, disciplinary beatings were the norm and sexual exploitation by Jones was a dirty secret shared by too many. And they wanted to stop him.

As some of his secrets were about to see print, Jones moved his flock en masse to the temple’s agricultural mission in Guyana. Ryan, after reading one of my stories and hearing complaints from his constituents, headed to Jonestown.

He brought along reporters, believing that we provided a measure of safety. Those of us accompanying the congressman thought he would afford us the same.

But Jones could not allow the congressman to leave with more than a dozen members who stepped forward and wanted out. He knew they would tell the world the ugly truth about Jonestown. About punishment in sensory deprivation boxes and pits. About the meager food and crowded barracks. About the suicide drills conducted by a raging tyrant with a pistol on his hip.

As Ryan’s party and the defectors were boarding two small planes, temple gunmen opened fire. Ryan, a defector and three newsmen, including Examiner photographer Greg Robinson, were killed, and many of us were wounded.

Jones used the massacre to help convince the Jonestown inhabitants that their fate was sealed. With armed guards around the pavilion, he exhorted his followers to take a sweet cyanide potion to thwart the enemies who would come to avenge Ryan’s slaying. He had the children go first, so the adults would have no reason to live.

In the aftermath, there were echoes of the temple’s violent demise. Jones’ former public relations chief called a news conference in a Modesto motel room, went into a bathroom and shot himself to death.

It was only after Jonestown died that I could get to know those who remained in the church but survived because fate put them someplace else that day. And they were not much different from those who escaped Jones’ grip. Archie Ijames, a tall sharecropper’s son who followed Jones from Indiana, confided many of the same excesses as the defectors had. And Jones’ own son, Stephan, spoke with bitterness toward his father and revealed that he and others had wanted to overthrow him before it was too late.

For years, the survivors stayed away from memorial services held each Nov. 18 at Oakland’s Evergreen Cemetery. Then Stephan Jones began to appear. So did his adopted brother Jim Jones Jr. So did a woman who sneaked away from Jonestown during the final hours. Some tearfully told their stories, yearning for lost loved ones and paying tribute to comrades committed to social justice. Even Jonestown, some said, was a wonderful place before Jim Jones came.

One of Ryan’s daughters, Patricia, comes to services and chats with the Jones brothers. Former enemies -- the loyalist survivors and the deserters -- embrace and reminisce. And on Sunday, a group of them gathered at the Oakland cemetery. Later, they socialized at a nearby home along with Larry Layton, who in Guyana had posed as a defector and shot two temple members. He was convicted of conspiring to kill Ryan and was paroled from the federal prison in Lompoc last year.

Among those at the reunion was Vern Gosney, a defector Layton shot in the back. Gosney lost his spleen and part of his liver, but he urged parole commissioners to let Layton out of prison.

“I could have been him,” said Gosney, now a police officer in Hawaii. “He is as much of a victim as I was of mind control and a dream that died. In forgiveness, there is freedom.”

Although drugs and the streets claimed some former temple members, many have made new lives through the sort of hard work and dedication they once put into the temple. The Jones brothers live in the Bay Area and have jobs and children. A temple handyman and mechanic now is a contractor. A temple bus driver became a bus company supervisor. There are office workers, writers, police officers, attorneys and even a preacher. As they were back then, they are ordinary people.

Some who were children in 1978 now have their own. One woman who lost her son in Jonestown brought her children to the graveside service. More than a few returned to Christianity after years of hearing Jones proclaim himself a socialist god on Earth.

Jonestown touched many who never cast their lot with the temple.

It touched parents who tried and failed to get their children out of the temple.

It touched politicians who welcomed Jones’ support, were hoodwinked -- or looked the other way -- and later paid a political price.

It touched ministers who lost members to Jones and saw them go to their deaths.

It touched the families of the newsmen who died doing their jobs.

And it touched Ryan’s family and his aide Jackie Speier, who survived her bullet wounds and went on to a career as a state assemblywoman and now a state senator.

On Tuesday, Speier and two of Ryan’s daughters conducted a memorial service in Foster City, on the San Francisco Peninsula, to honor the congressman. About 100 people attended the service, which featured a video on Ryan’s life, recalling the schoolteacher turned lawmaker who took on unpopular causes such as prison reform and saving baby seals.

“He was not defined by Jonestown, though this is the day we think about him most,” Erin Ryan, one of his daughters, told the crowd. “My father was a fighter for truth, justice and those who could not fight for themselves. He stepped onto that jungle airstrip doing what he did best.”

The Ryan family hopes to expand a Foster City memorial to the congressman, but in Oakland, a simple stone marks the grave of hundreds. Organizers there have wanted for years to build a wall chiseled with all 913 names of Jonestown’s dead.

That gesture was the dream of the family of Fred Lewis, a sad-eyed San Francisco butcher whose wife took his seven children to Jonestown and never came back.

Despite politicians’ promises and seed money from a businesswoman, there still is no wall. And Lewis missed the annual service for the first time this year. He died several months ago.

Leslie Wilson, who ran through the jungle to escape Jonestown, told mourners Tuesday: “For 25 years our people have been allowed to lay in a mass grave without even their names inscribed. How did we all allow this to happen?”

Reiterman, with the late John Jacobs, is the author of “Raven: The Untold Story of the Rev. Jim Jones and His People.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.