The African coup from central casting, circa 1980s

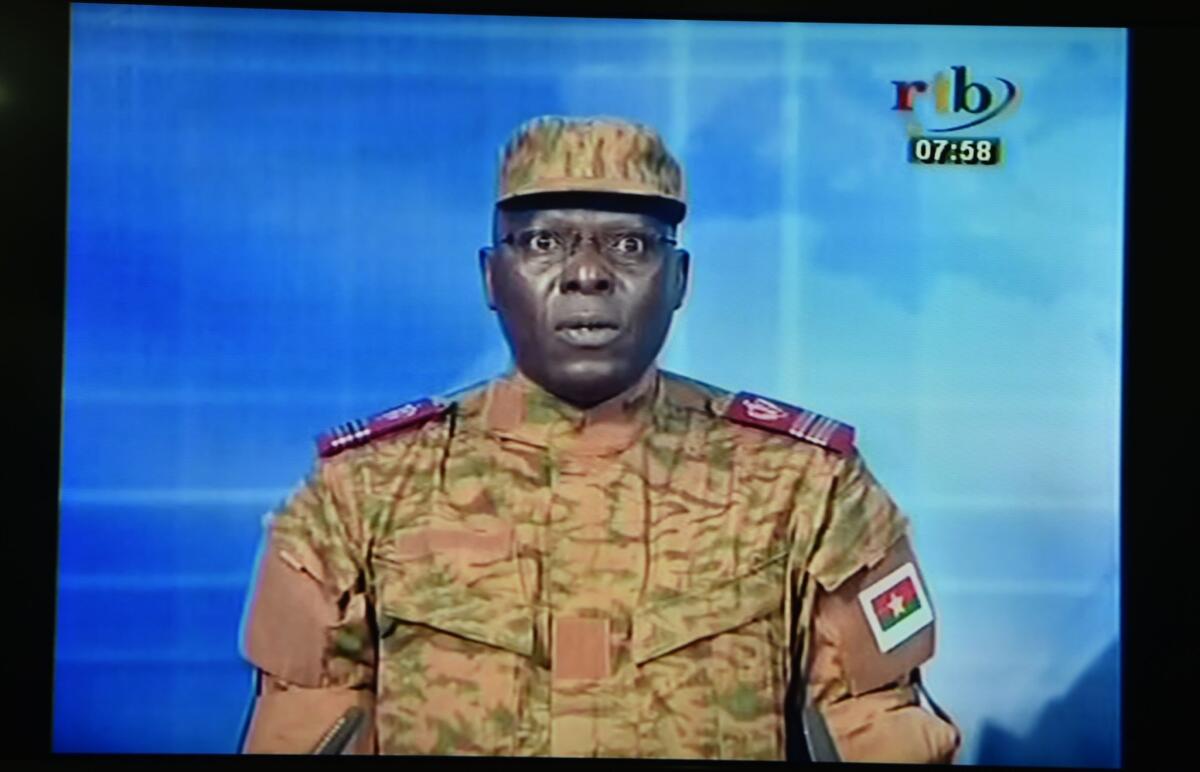

A picture taken on Thursday shows a TV screen during the broadcast of the speech of Lt. Col. Mamadou Bamba announcing that a new “National Democratic Council” had put an end “to the deviant regime of transition” in Burkina Faso.

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — It was a flashback to those old-fashioned African coups of decades ago, the ones that are not supposed to happen anymore.

We’ve all seen the movie: Soldiers burst into a cabinet meeting and arrest the president and prime minister, surround the building, fire on protesters and take control of state TV. An unidentified military officer comes on between cartoons and a football show to announce the government and parliament are no more.

That is the scenario that played out this week in Burkina Faso, signaling that the country’s old regime, a government that had clung to power for 27 years under former president Blaise Compaore, was essentially back, despite his toppling in mass protests last year.

The coup leader, Gen. Gilbert Diendere, is Compaore’s right-hand man and former chief of staff, a fellow with a finger in every pie in a region teeming with terrorist groups, kidnappers, arms dealers and smugglers.

He has also been close to U.S. and French security agencies and a key counter-terrorism ally. In fact he appears in his red beret on the U.S. military’s Africa Command center website, as a leader in the 2010 U.S. counter-terrorism training exercise in West Africa. (The coup has been condemned by U.S., French, U.N. and African Union officials.)

With Diendere in charge, questions inevitably rose as to whether Compaore was behind it. Or was it just other top members of the former regime, who were banned from contesting elections scheduled for Oct. 11, and wanted to engineer an election they could win?

How did Burkina Faso, a valued if not very democratic Western ally, go from being one of the region’s most stable countries to one of its messiest within a year?

NEWSLETTER: Get the day’s top headlines from Times Editor Davan Maharaj >>

The unpopular Compaore and his increasingly corrupt government were ousted in a revolution last October over his disputed bid to extend his term yet another five years. The country was being ruled on a temporary basis by Interim President Michel Kafando and Prime Minister Lt. Col. Yacouba Isaac Zida, who were ousted in the coup.

Their ouster threatens to launch a bloody fight for power with neither side willing to give ground.

“There’s a high risk. There’s already reports of shootings. It seems likely it could get worse,” said Paul Melly, an analyst with Chatham House, a London think tank.

There were local reports that the presidential security force that seized power had opened fire on protesters, killing at least one person and wounding dozens, with some reports of higher casualties.

“Basically, everyone will be horrified,” Melly said, referring to West African and Western leaders. “This is a complete disaster. It’s not what anybody thinks should happen in Burkina Faso.”

Compaore has a reputation as a tough politician, but if he thinks he can come floating back after a coup, “he must be more stupid than I thought he was,” Melly said, adding it was more likely an attempt by former regime heavyweights to engineer an election on their terms.

“To be honest, I expected something would happen, but I thought it would be more subtle,” said Cynthia Ohayon, a Burkina Faso analyst at the Brussels-based International Crisis Group, an analytical group. “This is a typical old-style coup. It’s like we’re back in the 1980s. We thought this kind of old-style coup can’t happen anymore because of international pressure. But apparently it can.”

In short form, what went wrong is this: Compaore tried to cling to power and was ousted a year ago after street demonstrations by a mass movement called Citizens Broom. A year-long transition to elections was set up, Compaore allies were arrested, then parliament passed a law in April banning former regime members from running in the presidential election – forgetting perhaps the old guard’s strong links with the military.

“They didn’t have the political strength to force through the level of political reform they wanted to,” said Melly.

Calls by a national reconciliation commission to abolish the powerful presidential security regiment, a 1,300-strong military unit stuffed with Compaore loyalists, seem to have been the last straw -- so the regiment launched its coup.

“Clearly they seized power to preserve the interests of the old regime,” said Ohayon. “They never accepted they lost power, because power means access to money and resources. They weren’t going to have the possibility to regain power through the ballot box so they went to another strategy, the strategy to use force.”

The coup comes with democracy being whittled back in some parts of Africa, as leaders ditch constitutional term limits to stay in power, often for decades. The Ugandan and Zimbabwean presidents have ruled since the 1980s; Burundi is edging toward civil war after the president insisted on a third term; and the presidents of Rwanda and Democratic Republic of Congo seem set to ditch the constitutional limit so they can stay on.

Unless the Burkina Faso coup leaders back down and a compromise deal is reached, the impoverished, landlocked country will doubtless be stripped of the Western aid it is utterly dependent on, risking collapse.

Given its location at the edge of one of the most dangerous terrorist belts in Africa, no one wants Burkina Faso to fall apart. Enormous international pressure will be placed upon both sides to settle the crisis.

Burkina Faso’s coup might look old style, but West Africa has changed in the last few decades and African leaders stand firm against military coups, though they’re more forgiving of rigged elections.

“It’s not sustainable,” said Ohayon. “The military is going to have to compromise. The other side will also have to compromise. The elections will have to be held eventually. The question is what the electoral conditions would be.”

See the most-read stories this hour >>

The coup leader, Diendere said next month’s election should be delayed and criticized the election code, the Associated Press reported.

Although Compaore and figures in the former regime have close links to the Ivory Coast political elite, Melly said Burkina Faso, which relies on transport routes through it and other neighboring countries, would be unlikely to withstand sanctions for long. Moreover, the West African single currency bloc could simply freeze its banking system, making it impossible to pay the army.

“If initial negotiations break down at some point, then some very serious sanctions levers could be applied. Some may think they would be able to hang on. They could become a criminal outlaw regime making deals with trans-Saharan drug smugglers and so on, but it’s hard to see how they could make it stick indefinitely,” Melly said.

Things would have been different had Compaore listened to French President Francois Hollande, who urged him in a letter last year not to try to run for office again, and promising French support to help find him a dignified role in some influential international organization, “if you wish to put your experience and talents at the disposal of the international community.”

Follow @RobynDixon_LAT for news from Africa

ALSO:

Chile weathers 8.3 quake and tsunami with moderate damage, but 11 die

Argentina remembers the future Pope Francis as a man of the people

Trickle of refugees becomes a flood in Croatia

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.