South Sudan’s president signs peace deal but has many qualms

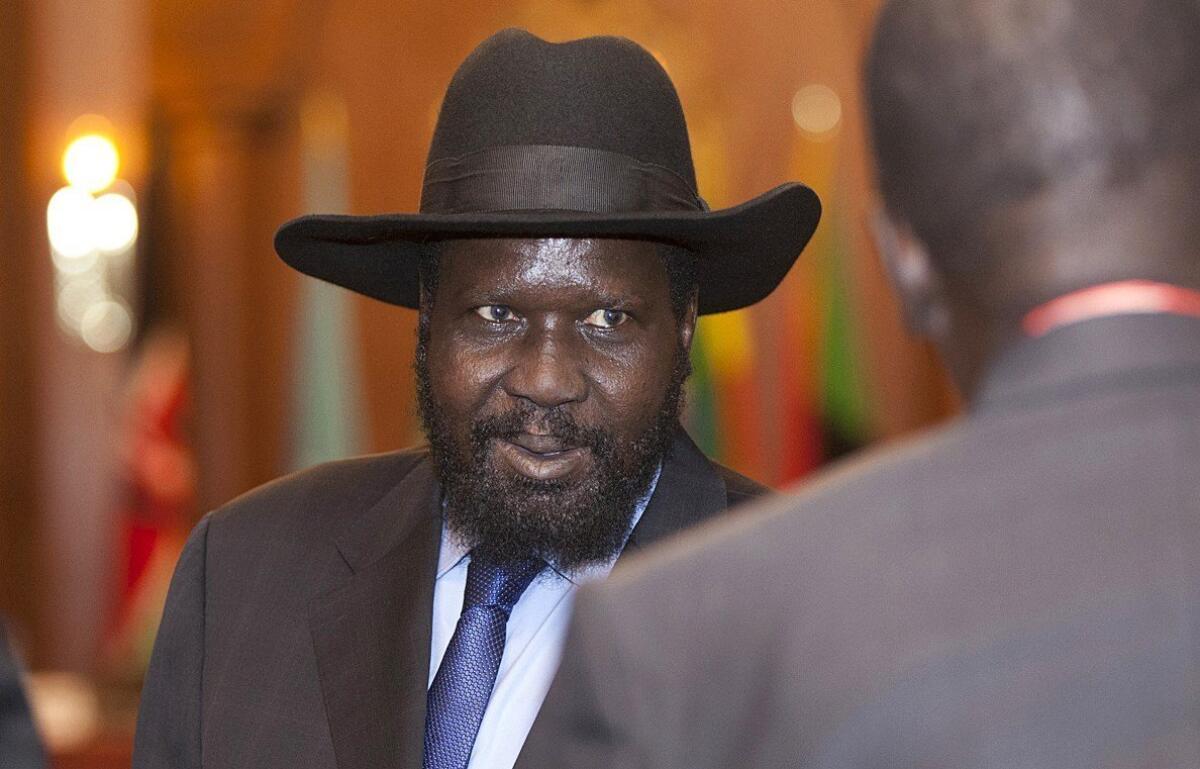

South Sudan’s president, Salva Kiir, arrives at a summit in Ethiopia on Jan. 29, 2015. Kiir signed a peace deal and power-sharing accord to end a 20-month civil war on Aug. 25.

Reporting from Johannesburg, South Africa — It took more than 20 months and seven failed deals and cease-fires for South Sudan’s fractious leaders to finally sign a peace agreement.

That was the easy part.

So what are the chances that two rival South Sudanese leaders — brilliant warriors who have been so far dismal at governing — will make this difficult peace accord work?

It should have been a hopeful moment as President Salva Kiir signed the agreement Wednesday in Juba, the capital, a week after other parties to the accord did so. However, his tone was so bitter that he sounded more like a man who had decided to not sign. He released a long list of concerns, saying peace was being “imposed” by the international community and calling for revisions.

He had one strong motive for signing the agreement, which will set up a national unity government in November for 30 months, followed by elections in 2018: If he didn’t sign, he risked United Nations sanctions.

Four years ago, South Sudan reveled in a brief moment of glorious optimism when a population that had endured 22 years of fighting for independence from Sudan finally — and peacefully — seceded.

What followed were horrifying betrayals of that hope. There was massive theft by government officials of oil money, which is the country’s main income. There was utter neglect of the basic duties of governance, with schools and hospitals largely dependent on international assistance.

And when it all fell apart in a ruling-party power struggle in 2013 that saw the government split and a rebel army rise, both sides committed atrocities, including ethnic killings and mass rapes of women, roping children together before cutting their throats and burning people to death in their houses.

With all the betrayals, the hate and the mistrust, making the promises of the peace accord a reality will be a daunting task.

“There’s been a real difficulty getting to this point,” said Ahmed Soliman, an analyst with the London-based think tank Chatham House. “The million-dollar question is whether the deal will stick or not. I think a lot of work has gone into the details, but there are a number of factors which can scupper that.”

The challenges are breathtaking. To start, there are the hard-liners in Kiir’s government and the army who are still convinced that the military could win. Then there are two sacked rebel generals who say the deal will never hold.

“There are always going to be spoilers. The key is to create enough momentum toward peace from the main actors who can deal with the spoilers,” said Justine Fleischner of the Enough Project, a human rights group that has long argued that without dismantling the lucrative benefits of a wartime economy for some elite South Sudanese, peace will remain elusive.

The problem with governments of national unity is that, while ending outright warfare, they often lead to paralysis as bitter opponents sitting together on a Cabinet find they can’t agree on much of anything.

In this case, the unity government risks turning into a presidential race, as the two main leaders — Kiir and rebel leader Riek Machar — try to use their government post to win the 2018 presidential race and sabotage each other, creating plenty of opportunity for jealousy and friction.

It was the rivalry between the two that triggered the civil war.

“You have got a short time of transitional government — 30 months — which is going to be marked by intense political competitions between the SPLM and SPLM in Opposition and former detainees,” said Soliman, referring to the three main parties to the peace deal. “It’s not going to be easy to get everyone working together if you have expanded ministries and turf battles.”

Then, there’s the question of the approximately 40,000 Nuer people languishing in camps for the displaced in Juba. They fled their homes after soldiers loyal to Kiir, a Dinka, began killing Nuers in December 2013 as civil war broke out.

Most of them are fearful, and many are angry. What happens when they go home? With Juba a tinderbox and with about 200 guards for each of the two leaders the only armed forces allowed in the capital under the deal, there’s fear of new violence.

Kiir and the government oppose removing the army from Juba. And the army opposes another key provision: reabsorbing Machar’s rebel forces into the military within 18 months.

“Having opposition and government forces armed in the same capital is going to require a level of troop discipline that we haven’t seen and that we can’t be confident exists,” Fleischner said.

“Signing the agreement is like the easy step compared with how difficult implementation will be,” she said. “There’s a trust deficit between the warring parties. They were both in power before the conflict broke out and it was their inability to come together that led to conflict in the first place. Managing those divisions is a very important part of this.”

The next big problem is the country’s short but vivid history of irresponsible, kleptocratic governance. Officials on both sides, it’s assumed, will continue stealing vast amounts of public money.

Kiir claimed in 2012 that $4 billion in government money had been stolen by officials. The luxury SUVs driven by even minor government functionaries in Juba are outward signs of the elite’s culture of siphoning off public money even as the masses live in dreadful poverty.

The latest deal is supposed to end theft of the nation’s oil wealth by setting up a monitoring body to ensure more transparency and accountability in the use of such revenue.

“The business-as-usual way the elites use the spoils of the oil to enrich themselves is threatened by the agreement,” Fleischner said.

Finally, there is the elephant in the room: the horrendous suffering of the communities that were attacked by forces led by the two main figures who will lead the unity government, Kiir and Machar.

Without prosecutions for the atrocities, there is little hope of the lasting reconciliation and tolerance on which nations are built. The deal sets up a hybrid African Union and South Sudanese court to deal with crimes against humanity, a delicate process that could bring more conflict.

“The agreement is far from perfect,” Fleischner said. “But it creates a framework to have the discussions they need to have, for instance the oil revenue: How should that be managed? Who has authority to write the checks? How do you prosecute corruption that has become so entrenched where everyone shares similar interests because … everyone had a piece of the pie?

“It’s creating accountability, where there was none.”

Follow @robyndixon_LAT on Twitter for news out of Africa

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.