Bundy cattle still grazing federal rangeland, 10 years after protesters’ armed standoff

- Share via

BUNKERVILLE, Nev. — The words “Revolution is Tradition” stenciled in fresh blue and red paint mark a cement wall in a dry river wash beneath a remote southern Nevada freeway overpass, where armed protesters and federal agents stared each other down through rifle sights 10 years ago.

Hundreds of backers of cattle rancher Cliven Bundy faced off with the U.S. Bureau of Land Management, which was trying to enforce court orders to remove his cattle from the rangeland surrounding his ranch. Bundy owed more than $1million in grazing fees.

Witnesses later said they feared the sound of a car backfiring would have unleashed a bloodbath. But no shots were fired, the government backed down and some 380 Bundy cattle that had been impounded were set free.

The cattle still graze the land. Ryan Bundy, eldest of the 14 Bundy siblings, said in a telephone interview that now, “The BLM doesn’t contact us, talk to us or bother us.”

“The BLM does not have any comment on this subject,” agency spokesman John Asselin said in response to email inquiries about the standoff, Bundy cattle grazing today in Gold Butte National Monument and the more than $1 million in unpaid grazing fees and penalties the Bureau of Land Management said Bundy owed in 2014.

The law was clear: Cliven Bundy’s cattle had been grazing on public land — illegally — for years.

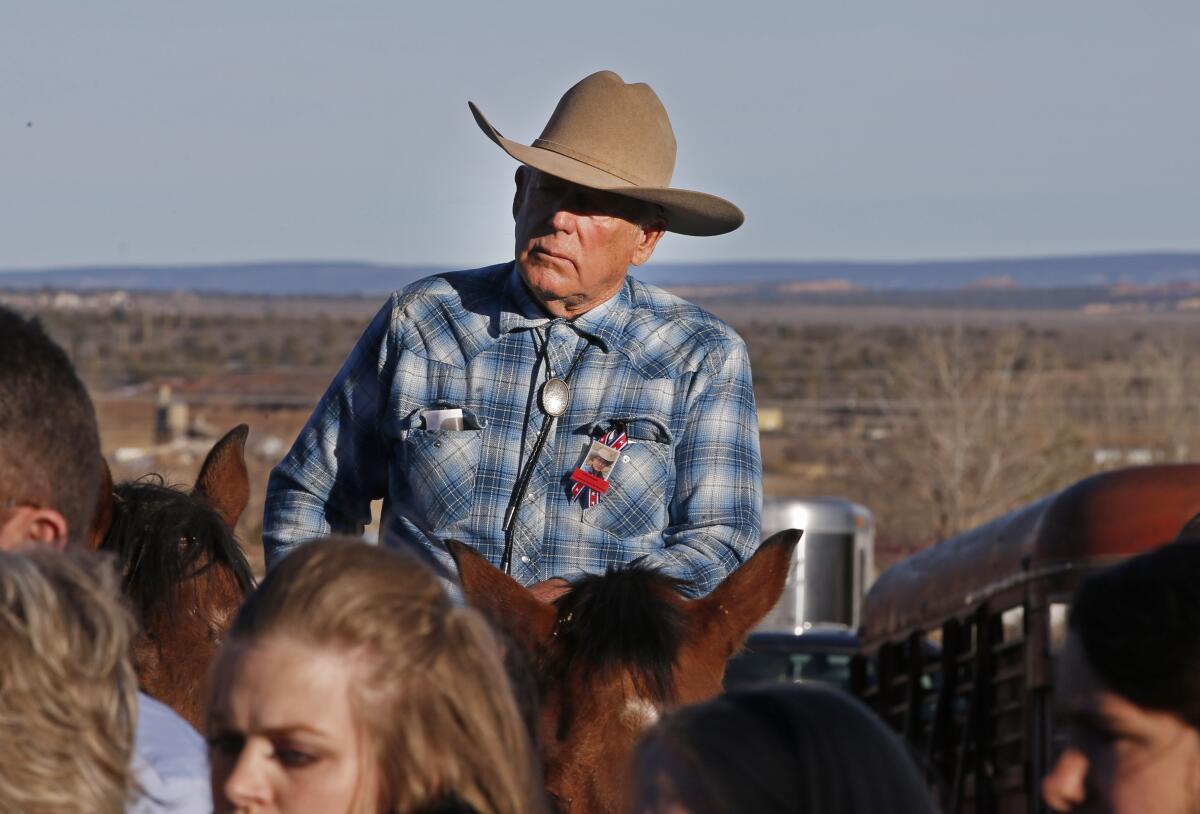

At the ranch, Cliven Bundy watched two of his sons and a friend rope yearling bulls in a pen as he recalled being arrested, jailed for nearly two years and brought to a trial that was dismissed because of prosecutorial misconduct.

“I’ve had that dot on my forehead and on my chest,” the 77-year-old Bundy said of the feeling of being in target crosshairs. Courtroom evidence later revealed that federal agents with rifles had camped in hills around Bundy’s ranch before and during the showdown on April 12, 2014.

Bundy claims his family and followers were unfairly targeted by heavy-handed government agents but rescued by backers including militia members.

The outcome of the tense confrontation reverberated. In January 2016, Bundy’s eldest sons, Ammon and Ryan Bundy, and several other men who were at the Bundy ranch in 2014 led a weeks-long armed standoff at the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon. It ended with their arrests after LaVoy Finicum was shot dead by state police at an FBI roadblock.

Some heard echoes of Bunkerville and Malheur when Trump supporters attacked the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021, and temporarily blocked certification of the 2020 presidential election.

“Bunkerville was an early warning sign of the MAGA/Trump movement,” said Ian Bartrum, a University of Nevada, Las Vegas, law professor who has studied and written about the standoff and federal land policy. He cited “a growing militia movement looking for someone to fight.”

“I think we can safely say, 10 years later, the Bundys won that fight, and federal regulators don’t seem at all eager to try again,” Bartrum said. “We have bigger problems than cattle on public land at this point.”

In court, federal prosecutors said the Bunkerville confrontation was an insurrection against the U.S. government. Nineteen people from 11 states, including Bundy and four sons, were arrested in 2016 on charges including conspiracy, assault on a federal officer and firearms counts. Most remained jailed for nearly two years.

Five defendants pleaded guilty before trial, several were acquitted and some were convicted of lesser charges. One remains in federal prison. None of the Bundys was convicted of a crime.

Today, family members estimate that more than 700 Bundy cattle graze widely in the Virgin River valley surrounding the 160-acre Bundy ranch and in Gold Butte, a scenic and archaeologically rich Mojave Desert expanse half the size of Delaware that President Obama designated a national monument in December 2016.

Conservation groups including the Center for Biological Diversity and Western Watersheds Project are suing to prod the government to remove cattle and protect the desert tortoise, a species deemed in 1990 to be threatened by habitat loss that advocates blame on grazing.

“The desert tortoise is at the heart of it,” said Erik Molvar, Western Watersheds executive director. “Cattle continue to graze illegally ... causing irreversible damage to ecological values.

“I think you can look at the Capitol insurrection on Jan. 6 and draw a straight line to Malheur and Bunkerville,” Molvar added, “as emblematic of insurrectionist movements in the United States and the failure of federal prosecutors to fully enforce the laws.”

Bundy claims the federal government does not have authority to regulate lands his Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints family settled some 150 years ago. He insists questions of local sovereignty have never been answered to his satisfaction.

Asked what would happen if the government tried again to round up Bundy cattle, Bundy said, “There was 1,000 there last time. There’ll be 10,000 there next time.”

Ritter writes for the Associated Press.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.