Amid fury over Nagorno-Karabakh, could Armenia’s government fall next?

- Share via

BEIRUT — Days after Azerbaijan defeated the ethnic Armenian authorities who have long ruled the separatist region of Nagorno-Karabakh, speculation is swirling over whether another government could fall: that of Armenia itself.

As tens of thousands of Nagorno-Karabakh’s residents flee, abandoning their homes amid fear of Azerbaijani rule, rage has filled the streets of Yerevan, Armenia’s capital. Thousands of protesters have thronged Republic Square each day, attacking government buildings and facing off against riot police, their fury focused on Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and what they say is his inaction before the prospect of genocide in Nagorno-Karabakh, which Armenians call Artsakh.

“People want to punish the one who will hand over Artsakh to a foreign nation,” said Hovhannes Ishkhanyan, a Yerevan-based documentary filmmaker.

“There is huge anger against Pashinyan, and that’s how it should be.”

That anger persisted Wednesday, with the total number of refugees leaving Nagorno-Karabakh and crossing the border into Armenia over the last few days rising to more than 42,000, according to the Armenian government. (Estimates put Nagorno-Karabakh’s ethnic Armenian population at 120,000; Azerbaijan officials insist the true figure is lower.)

They arrived crammed into whatever vehicles they could find, many of them with little more than a change of clothes. Behind them were tens of thousands of others crowding a mountain highway. The 25-mile drive from the region’s capital, Stepanakert — Azerbaijan calls it Khankendi — to the Armenian border took some as long as 20 hours.

Ethnic Armenians are fleeing Nagorno-Karabakh over the border to Armenia, as Azerbaijan asserts full control over the enclave Armenians call Artsakh.

“Just a river of cars. We drove two meters, waited two hours,” tweeted Marut Vanyan, a journalist who arrived in Armenia on Monday after leaving Stepanakert. That night, an explosion ripped through a gas station outside the capital, killing 68 people and injuring scores of others waiting in line for fuel.

The chaos at the border and in Yerevan has only swelled the outrage at the Armenian government, especially Pashinyan, whom critics accuse of capitulating to Azerbaijan by failing to send troops to Nagorno-Karabakh to protect its ethnic Armenians. In Yerevan, protesters blocked roads, while authorities arrested demonstrating students at the American University of Armenia, adding to the hundreds of people detained by police over the last few days.

Rallies calling for Pashinyan’s impeachment have filled Republic Square, the same public plaza where he addressed supporters during the 2018 revolution that brought him to power, ending the rule of what many believed to be a hopelessly corrupt political class.

Whether Pashinyan will step down or can be ousted without an election is unclear, and many of the alternative candidates, who are mostly associated with pre-2018 governments, seem to their compatriots even less savory.

But the risk of Pashinyan’s government falling is very real, said Thomas de Waal, a Caucasus expert at Carnegie Europe.

“There are tens of thousands of Karabakhis fleeing to Armenia who feel that Pashinyan has betrayed them as well as large parts of the Armenian establishment for whom Karabakh was a sacred cause,” he said.

For those out on the streets demanding Pashinyan’s resignation or removal, the very survival of their country is at stake, said Beniamin Matevosyan, an analyst with the Yerevan-based Politeconomy Research Institute. They fear that Azerbaijan, emboldened by its victory in Nagorno-Karabakh, could attack Armenia itself.

Tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan are high again two years after they ended a war over Nagorno-Karabakh that killed about 6,800 soldiers.

“The question isn’t ‘Is there a chance for the Pashinyan government to fall,’ but ‘Is there a chance to save Armenia?’” he said. “It is precisely in order to preserve Armenian statehood that people go to protests.”

Azerbaijan signaled its intention to impose swift and strict control on Nagorno-Karabakh by arresting a former head of the region’s secessionist government Wednesday as he tried to join the river of people crossing into Armenia. Ruben Vardanyan, who stepped down from his post earlier this year, was taken to Baku, the Azerbaijani capital, where “relevant state bodies” will decide his fate, the border guard service said.

The festering ethnic conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh began amid the splintering of the Soviet Union, when ethnic Armenians in the territory, which is roughly the size of Rhode Island, chose to secede from Azerbaijan and unite with Armenia in 1988. In the ensuing six-year war, some 30,000 people were killed amid accusations of ethnic cleansing on both sides.

By 1994, Nagorno-Karabakh, along with the mostly Azeri-populated provinces surrounding it, fell under the control of Armenia-backed separatists. A government funded and equipped by Yerevan called itself the Artsakh Republic, though international law recognized the area as Azerbaijan.

Their decades-old battle over the mountainous territory of Nagorno-Karabakh has come to define how Armenians and Azerbaijanis view themselves.

In 2020, Azerbaijan’s military took back much of the area around Nagorno-Karabakh. In December, Azerbaijan blocked the only land link between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, despite the presence of Russian peacekeeping troops.

Last week, Azerbaijan launched a swift military campaign and surrounded Stepanakert. Assurances from Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev that his government would treat ethnic Armenian residents in Nagorno-Karabakh as equal citizens did little to stop their exodus.

Despite Armenia being part of a collective security agreement with Russia, Moscow did not intervene. But neither did Pashinyan.

Some say he simply accepted that Azerbaijan’s army was larger and far better-equipped and that with the Artsakh Republic unrecognized by much of the world, he had little room to maneuver. His supporters insist that giving up on Nagorno-Karabakh will allow Armenia to forge links with its neighbors and bring much-needed investment.

Yet many in Armenia and among its large and influential diaspora are furious, seeing in Pashinyan a Neville Chamberlain-like figure whose appeasement of Azerbaijan will only encourage it to go for more. On Tuesday, dozens of Armenian Americans and supporters rallied in Simi Valley, outside the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library, in support of ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Some critics point to Aliyev’s recent statements regarding Armenia’s southern Syunik region, which Azerbaijan calls Zangezur, through which he aims to construct a land corridor linking Azerbaijan to Nakhchivan, an autonomous Azerbaijani exclave wedged between Armenia, Iran and Turkey. Under the 2020 cease-fire agreement, Azerbaijan and Armenia were to restore transport connections, but Armenia fears that could lead to its being cut off from its southern border with Iran.

On Monday, Aliyev blamed Soviet-era authorities for apportioning territory to the Armenian Soviet republic that he believes should have belonged to the Azerbaijani Soviet republic. In past speeches, he has also used the irredentist term “West Azerbaijan” to refer to swaths of Armenia — including Syunik — that he believes rightfully belong to his country.

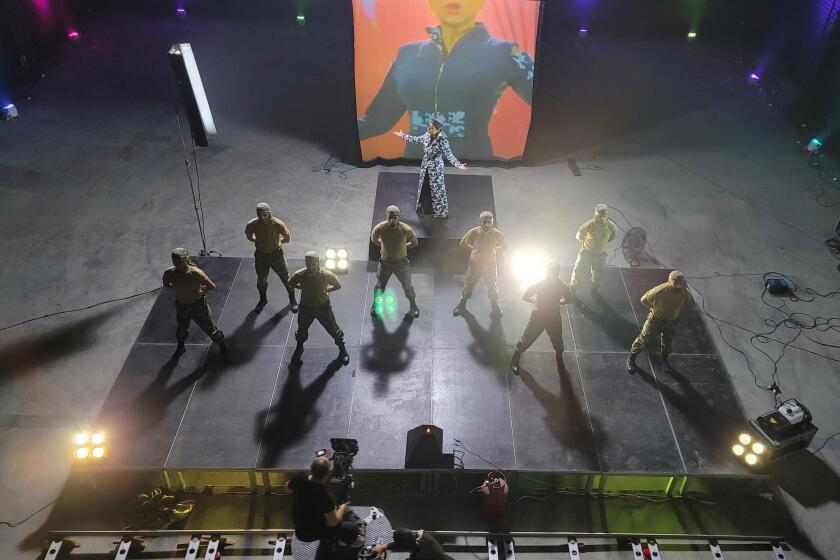

Armenia and Azerbaijan enlist artists, lobbyists and online activists in a 21st century propaganda war in their fight over Nagorno-Karabakh.

“Anyone following Aliyev’s rhetoric closely knows this is not just about Artsakh. He’ll go after Zangezur and other areas, and there’s nothing there to stop him. And certainly not Pashinyan,” said David Grigorian, a veteran Armenian analyst and senior fellow at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “I would say without Artsakh there is no Armenia, because without Zangezur there is no Armenian economy.”

This week, the U.S. dispatched Yuri Kim, an acting assistant secretary of State, and Samantha Power, the U.S. Agency for International Development administrator, to Yerevan to meet with Pashinyan and emphasize Washington’s view that the cease-fire must remain in place, with no further violations from either side.

Power said she wanted to make “very, very clear” the support from many United Nations member states “for Armenia’s sovereignty, territorial integrity, and democracy.”

“I’m not going to preview what the consequences would be of violating those precepts, but it’s absolutely imperative that the world stand together now and stress the inviolability of those principles,” she said.

News Alerts

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

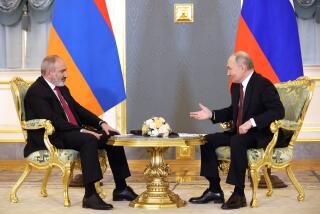

Washington’s support comes as Pashinyan blames longtime ally Russia for failing to prevent the loss of Nagorno-Karabakh. With Moscow’s focus on the war in Ukraine, Pashinyan has questioned the worth of the collective security agreement and indicated a desire for a closer relationship with the U.S.

In response, Russia’s Foreign Ministry accused Pashinyan of shifting responsibility for his failures and of mishandling the conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh since 2020. It also painted the West’s maneuvers in Armenia as part of a wider strategy to turn regional governments against Russia, and warned Pashinyan’s government not to sever Armenia’s ties with Russia in order to become “a hostage to Western geopolitical games.”

“The Russians now obviously want Pashinyan out and are pretty much openly calling for street demonstrations,” De Waal said. “Perhaps that is his strongest card — that much as the public is angry with Pashinyan over this, they are even more angry with Russia’s duplicity.”

Yet for many protesters on the street, Pashinyan’s international maneuvering matters little in the face of what they say is his turning his back on ethnic Armenians in Nagorno-Karabakh.

“Basically this guy came in to hand over Artsakh,” said Ishkhanyan, the documentary filmmaker.

“These protests will continue until the last Armenian.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.