Saving an election on Insta: Guatemalans go to social media to try to protect presidential vote

MEXICO CITY — As their presidential election hangs in the balance, Guatemalans are taking to social media to try to circumvent what they see as interference and a threat to democracy.

After an anti-corruption candidate stunned with a second-place finish last month and advanced to the August runoff, Guatemala’s Constitutional Court on Saturday ordered the election results suspended and reviewed.

The court’s move has raised cries from international observers as well as Guatemalans over election meddling. The second-place candidate, Bernardo Arévalo of the Semilla party, said in an interview that the move is a desperate attempt by the conservative establishment to maintain control: “It’s the modus operandi of a co-opted state.”

So now, in a country where leaders have eroded democracy, voters are taking matters into their own hands to safeguard the election results.

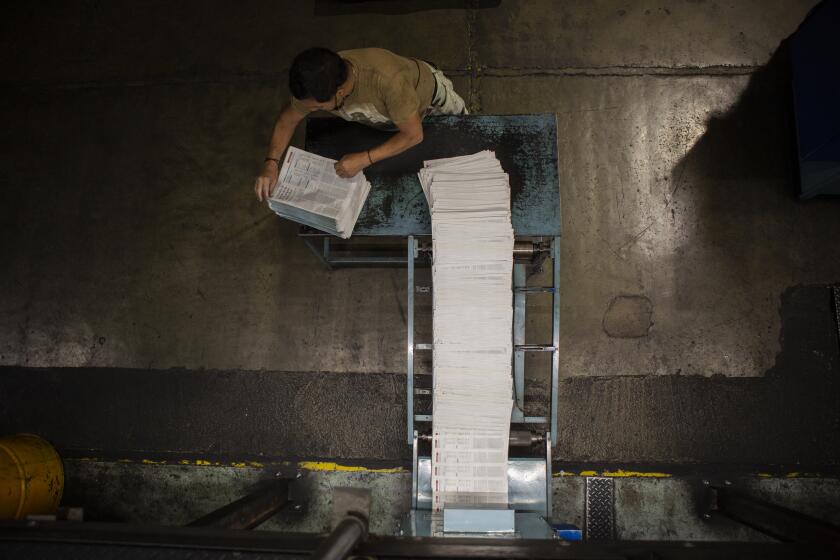

Supporters of Arévalo’s party are posting certified election results from their voting tables on social media, after downloading scanned PDFs from a government website. The PDF forms show how people voted at each table.

Hundreds if not thousands of forms containing election results have been posted, with the hashtag #NoHuboFraude — #ThereWasn’tFraud — becoming a trend on Twitter. Besides raising awareness, by downloading the forms, citizens can confirm firsthand that the votes at their polling table were tallied correctly.

“I did it as an act to make my vote count, to show that there wasn’t fraud,” said Andrea Yanes, a 24-year-old international relations student at Rafael Landivar University in Guatemala City who posted her form on Twitter and has helped friends and relatives download the scanned forms.

The daughter of a Guatemalan dictator convicted of genocide is running for president, raising questions about the nation’s memory of a brutal civil war.

Edgar Ortiz Romero, a constitutional law expert at Istmo University just outside Guatemala City, said the social media movement has turned into “an exercise of publicity to defend our system.”

“It’s surprised me a lot that people are doing this,” he said. “I think it’s because a narrative of fraud has never gone so far before.”

Samuel Pérez, a 30-year-old party leader of Semilla — or Seed — said the trend took off after a party effort to combat claims of voter fraud. Before the Constitutional Court suspended the election results, Pérez noticed that social media accounts were circulating a picture of a form that contained errors, using it to accuse Semilla of fraud. Pérez instructed party representatives to publish images of other, accurate, forms.

The presidential election was marked by low turnout, and about a quarter of ballots were left blank or nullified, which can happen when a ballot is deliberately defaced. Courts had blocked several people from running, including a leftist Indigenous candidate and a popular political-outsider businessman.

In the crowded election, Arévalo got 11.7% of the vote and Sandra Torres, a former first lady backed by conservatives, received 15.8%. The third-place finisher received 7.8%.

The Organization of American States and European Union, which monitored the race, did not report major issues on election day. The OAS, urging that “the will of the people expressed at the polls be respected,” said it would send election monitors back to Guatemala for the review.

The U.S. State Department said it is “deeply concerned by efforts that interfere with the June 25 election result.” A powerful indigenous Guatemalan group has threatened to hold mass protests.

The deadly fire at a migrant detention center in Mexico highlights why, amid harsh U.S. immigration policies, migrants make the journey to the border.

Democracy and rule of law have been under attack in Guatemala for years.

The most significant blow came in 2019, when then-President Jimmy Morales expelled a United Nations-backed anti-corruption commission after it began investigating him over illegal campaign financing. Anti-corruption prosecutors and independent judges have fled the country under his successor, President Alejandro Giammattei. The attorney general in 2021 fired the country’s top anti-corruption prosecutor, drawing sanctions from the U.S.

Recent attacks on Judge Miguel Ángel Gálvez are part of a broader campaign on Guatemala’s courts that have forced nearly two dozen judges and prosecutors into exile.

Human rights groups have also decried attacks against journalists. A major Guatemalan newspaper closed in May after its staff faced criminal investigations it has called revenge for its corruption investigations. (The founder, renowned journalist José Ruben Zamora, has been sentenced to six years in prison in a money-laundering case he says is fabricated.)

What would become the Semilla party began as a small group of intellectuals meeting to discuss what they saw as the country’s troublesome state of democracy. When a corruption scandal triggered mass protests that forced President Otto Pérez Molina to resign in 2015, the group decided to form a party. It coalesced around social democratic ideals and aimed to combat corruption, said Samuel Pérez.

Semilla’s first pick for a presidential candidate, Thelma Aldana, wasn’t allowed on the 2019 ballot. The Constitutional Court barred the former attorney general from running after she faced corruption charges — a move that human rights groups called payback for her office’s anti-corruption work, which included the prosecution of Pérez Molina.

Under a law meant to crack down on violence against women, politicians obtain restraining orders to stop reporters from criticizing them or investigating corruption.

This year, the party backed Arévalo, 64, the son of a literature professor considered Guatemala’s first democratically elected president, who won in 1944 after protests ousted a military dictator. Arévalo, who has a sociology degree, has served as vice minister of foreign affairs and ambassador to Spain, and spent years doing work for the organization Interpeace.

In 2020, he became a congressman for Semilla, which has developed a detailed government plan to expand social services but presents fighting corruption as the most urgent problem. Arévalo has said that he’d bring back prosecutors and judges who have fled Guatemala under persecution from the conservative-run judicial system.

Arévalo said Semilla’s success in the most recent election reflects Guatemalans’ weariness.

“We were able to capitalize on the frustration, on the tiredness of a population that doesn’t want to keep living a corruption disaster,” he said.

Another factor, according to Will Freeman, a fellow for Latin American studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, is that “so many establishment parties fighting for power” helped Semilla.

“Their votes are so concentrated in these urban centers where maybe people are more tuned in to the type of pro-transparency, pro-reform politics they’ve been trying to build,” he said.

Several days after the election, 10 parties solicited an injunction with the Constitutional Court, saying there were problems with the count. The court ordered citizen volunteer committees that certified vote results to hear complaints and cross-check tallies.

Torres — a runner-up in two presidential elections who was arrested in 2019 on campaign finance charges before a judge threw out the case — has said that she asked for the injunction “for protection.”

“If the records are good, if the numbers are good, then nothing happens,” she told reporters in a news conference. “The only thing we want is to give legitimacy to the process.”

Arévalo has called it a ploy by the other parties to overturn the results. The elections also included races to choose lawmakers, and Semilla more than tripled its congressional seats. “They are about to lose control,” he said.

Oritz Romero, the constitutional law expert, said the review is an “unnecessary process” that may erode confidence in the electoral system. It’s unclear, he said, how long it could take to reach a resolution.

For now, Semilla is rallying its base. More than 15,000 people have signed up in the last few days to volunteer for the party, said Pérez.

Among the volunteers is David Ortiz, 32, who works at an art gallery in Guatemala City.

Ortiz decided to vote for Semilla after Arévalo showed up one day last spring at the gallery and the two began chatting about artists. Ortiz likes the party’s anti-corruption rhetoric and its promise to bring back attorneys and judges who have fled the country.

He was furious when the election results were suspended. After seeing that friends were posting the certified voting forms on Instagram, he went online to download the form that corresponded to his voting area.

He posted the photo on Twitter, writing that “there weren’t any alterations, nor corrections, nor FRAUD.”

“It was really an act against the corruption, against those who have always governed to say that ‘you yourselves put this system in place for us to consult,’” he said. “We’re not going to stay silent.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.