- Share via

TIJUANA — From the last row of his fourth-grade classroom in Tijuana, Fleurin Fletcher stares blankly at the board, trying to comprehend lessons in a language he doesn’t speak or read.

When it comes time to solve two-digit multiplication problems, he adds the numbers instead.

He erases and copies down the correct answers without really understanding why they are correct. The class moves on.

This story is for subscribers

We offer subscribers exclusive access to our best journalism.

Thank you for your support.

The 10-year-old is one of two Haitian migrants in a classroom of nearly 30 students, and his struggles to adapt to schooling in a foreign country are emblematic of a broader challenge facing both students and the public education system across Mexico.

In recent years, more migrant and asylum-seeking families are choosing to stay in Mexico as the American dream fades away. Others are biding their time, waiting for an opportunity to cross into the United States.

From 2020 to 2021, the number of children and teens who requested asylum in Mexico jumped from around 8,000 to almost 32,000, according to the United Nations and Mexico’s refugee aid commission.

Children from Central America, the Caribbean and beyond are arriving in Mexico sometimes without speaking Spanish, with educational lags brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic or a more substantial lack of schooling in their home countries. Many are also carrying trauma — of their long journeys across the Americas, of violence and poverty, and of family separation.

While they make up only a small percentage of the almost 33 million K-12 students enrolled in Mexican schools, the education system finds itself at a crossroads: identify and invest in the needs of the country’s growing population of migrant and refugee children, or risk broader social and economic repercussions as these youth are left behind.

In Baja California, at least 46,000 foreign students of 70 nationalities enrolled last academic year in schools, according to Baja California’s Binational Migrant Education Program, or PROBEM in Spanish.

Former Mexican security minister Genaro García Luna is on trial in Brooklyn, accused of taking bribes from ‘El Chapo’ Guzmán’s Sinaloa drug cartel.

However, at a national level, Mexico’s Department of Education lacks statistics on the number of foreign students in the system, their backgrounds, and where they go to school, which in turn prevents school administrators and policymakers from assigning resources accordingly.

“Migrant students are an invisible population,” said Yara Amparo López, the head of PROBEM.

Education is a constitutional right of all children in Mexico regardless of immigration status. The law also stipulates that education must be equitable and “of excellence,” with special attention paid to children of other nationalities, immigration backgrounds and other conditions of vulnerability. Baja California’s education program goes a step beyond, recognizing children’s right to education with inclusion and equity, referring particularly to “repatriated, foreign or migrant” students.

Still, the problems can start as early as enrollment.

Mexico has eliminated bureaucratic barriers over the years to ensure access to education, including no longer requiring birth certificates or notarized translations of official documents. But hurdles persist.

Lack of information from migrant parents, on top of disinformation about what is required to enroll, can delay children from accessing education. Confusion from administrators further delays enrollment.

“Not all school authorities are aware of the changes in the legislation because they are not in contact with this population or only have a couple of students,” said Mariana Echandi, an officer at the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in Mexico.

By the time many migrant families arrive in a border city, children might have spent months without going to school.

“The longer a child stays out of school, the harder it’s for him to go back,” Echandi said.

Meanwhile, the pandemic has exacerbated other challenges already faced by Mexico’s public education system. Studies show that the amount of children from low socioeconomic backgrounds in Mexico who can’t read or write is set to increase 25% due to school closures during the pandemic. Prior to the pandemic, 6 out of 10 students in Baja California were performing low in math.

Language barriers

Sindicato Alba Roja Elementary School, located less than a mile from the U.S.-Mexico border in downtown Tijuana, has been put to the test. It is one of the many schools that offer morning and evening shifts due to high demand and low supply. Students go to school only four hours a day.

The school is an attractive option for migrant families who want to stay in the bustling city center where commerce thrives or close to the border, according to Iraice Abigail Prado, who has been Alba Roja’s evening principal for six years. Migrant shelters, community centers and Mexico’s Commission for Refugee Aid are also nearby.

About 33 migrant students registered in Alba Roja’s evening school and 36 in the morning school at the start of the current academic year, according to PROBEM.

The school also serves low-income Mexican students, many of whom live in the area and are exposed to nearby high-risk environments, including homeless encampments, bars and the city’s red-light district.

The school’s foreign students often reflect migration trends to the border region.

A few years ago, the school had a significant population of Chinese students.

Last academic year, at least 38 migrant children, many of them from Central America and the Caribbean, enrolled in the school, according to PROBEM.

Fleurin was one of them.

He and his family arrived from Haiti in early 2022, joining thousands of others hoping to request asylum in the United States. Since Haitians began arriving in large numbers in 2016 after Hurricane Matthew devastated the island, many have been forced to stay in the city for months waiting for their immigration proceedings in the United States. Others have chosen to stay.

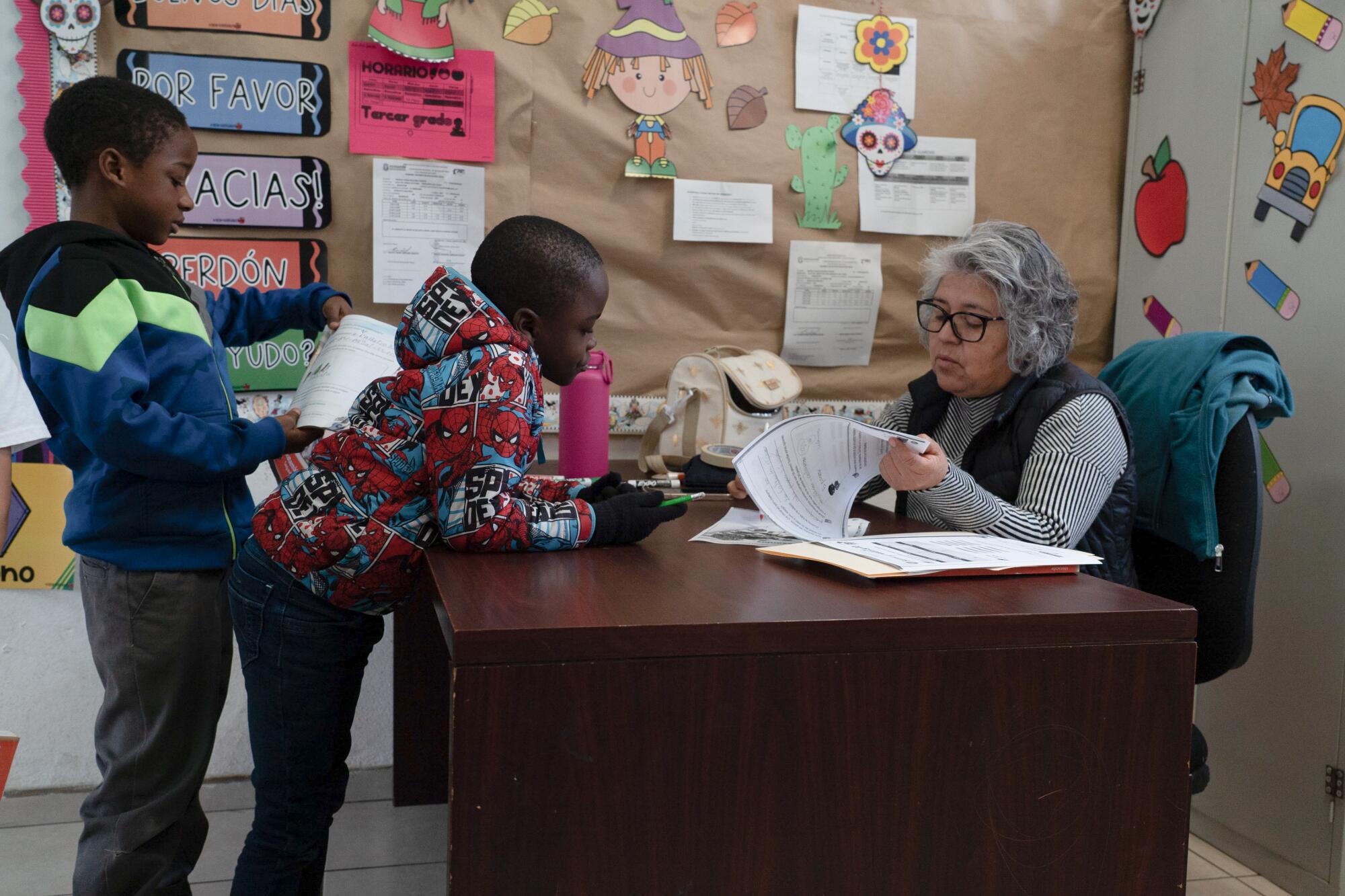

At Alba Roja, teachers have paired foreign students with their local classmates to encourage friendship and support, a tactic that has shown success. It was teachers who were adrift.

“Imagine having to assist a student who speaks French, another who speaks Creole, one who can’t do his assignment, another who doesn’t understand,” explained Donají Martínez, a second-grade teacher who has worked at Alba Roja for 20 years.

Enrique Felix Carrazco, a fifth-grade teacher at Alba Roja, reads his tests aloud using simplified language and relies on Google translate to communicate with his Haitian students. “It’s slow but effective,” he said.

To foster empathy among his Mexican students, he once asked the class to guess a word using only signs. “That’s how your Haitian classmates feel when they get an instruction in Spanish,” he told the class. “We want them to speak our language, but we are not doing anything to learn theirs; we want them to adapt to us, but we haven’t adapted to their culture.”

Edith León Castillo was Fleurin’s third-grade teacher when he first arrived. Fleurin couldn’t hold his pencil correctly or write down his name.

When Fleurin started crying on his first day of school, León rushed to find one of the Haitian students to help. That’s when she learned that not all Haitian children spoke the same language — some spoke Portuguese, others Creole and others French. Fleurin’s shyness made it impossible for the other kids to understand him.

León searched for Creole lessons that same day. “The few places that offered them were already full,” she said. She was feeling desperate.

“Seeing him cry really made an impression on me,” she said. “I felt bad that I couldn’t do anything to communicate with him.” Then it hit her: She would ask her mother, who worked in a uniform factory with Haitian colleagues. She began learning Creole with one of them that same weekend.

“There’s no reason why he should adapt to me when I can do more for him,” León said. “I wanted him to see that I could speak a bit of his language so he could feel more comfortable, and I think I succeeded.”

The Mexican education system has yet to create curricula for teaching Spanish as a second language or establish resources to respond to the particular needs of migrant and refugee populations. At the state level, PROBEM, the migrant education program, has offered teacher training, outreach to schools and worked with UNICEF to guarantee access to education, but many of its responsibilities have not officially been established in its governing rules and operations.

Most teachers are still left on their own. Like many teachers in states where there is a PROBEM office, León didn’t know of its existence.

“No one ever guided me,” León said. “They just told me, here’s the kid and that’s it.”

Battling stigma

Many migrant families don’t know about PROBEM, either.

PROBEM intervenes directly when a foreign student is denied access to schooling for not having birth certificates, transcripts or other paperwork, which is no longer a requisite for enrollment at the primary level. But oftentimes it is up to the student’s family to contact PROBEM for help.

Prado, Alba Roja’s evening principal, said she has admitted migrant families after they were turned away by administrators at other schools claiming there was no availability, which she said were likely lies.

From Noah’s Ark to the Aztecs’ Tlāloc, rain shapes spiritual beliefs, both as giver and destroyer of life. No wonder Californians pray for it but fear it.

The highly mobile nature of migrants and asylum seekers in border towns also adds to the stigma children face. Some teachers see their arrival as a nuisance since it’s likely many children won’t finish the school year, explained Echandi from the United Nations.

U.S. immigration policies such as “Remain in Mexico,” which forced people to wait out their U.S. asylum proceedings in Mexico, and Title 42, which expels them from U.S. soil, have kept many families in limbo and rippled across children’s ability to integrate and study in Mexico.

At Alba Roja, the typical Haitian student doesn’t stay in school for more than two years, according to Prado, Alba Roja’s principal. Prado says some migrant parents don’t alert the school when they are finally able to enter the United States. Children just stop showing up.

The experience of migration also makes it hard for many parents to get involved in their child’s education. Language often hampers teacher-parent communication, and many migrant and refugee parents work two jobs with barely any time off.

Fleurin’s father, Michel Fletcher, arrived in Tijuana in 2016 alone. It took him around five years to bring his wife and two youngest children, Fleurin and Dawendjina, 12, to Tijuana through family reunification. Fletcher was able to obtain a Mexican residency permit that expires later this year.

Two other children are still in Haiti, while another two are in Brazil.

The Fletchers live in a small one-bedroom apartment downtown, about a mile from Alba Roja. Their place is crowded and cold in the winter, but they make do.

On the weekends they sell second-hand clothing, kitchenware, old electronics, buckets, chairs and all kinds of trinkets on the sidewalk outside their apartment. Fleurin’s mother, Antoinette Darelus, sometimes sells fried plantain chips in the neighborhood, and Fletcher offers translation services from Creole to Spanish outside Mexico’s immigration office.

After decades of falling enrollment exacerbated by the pandemic, Los Angeles Catholic schools are on track for a second straight year of enrollment growth.

“We make enough for food, which is not a lot but it’s enough,” Fletcher said. His wife and children are better off than they were in Pilate, a rural town in Haiti where the family grew crops to sell in the local market, he said.

“They were just surviving in Haiti,” said Fletcher, who spent long stretches of time in the Dominican Republic to make ends meet. He then moved to Brazil for a few years before migrating to Mexico. As the youngest of six, Fleurin practically grew up without his father.

Addressing trauma

Many school administrators focus on the language barrier as the most pressing challenge. But López, PROBEM’s director, said the education system must dig deeper to serve its migrant and refugee students.

“Once, a principal asked me for a Russian-to-Spanish interpreter, and I offered her my phone because we don’t have resources for interpreters,” she recalled telling her.

“The principal wasn’t thinking of the child’s psychosocial needs, how to integrate him in the classroom, how to teach him math without speaking Russian, or how they would teach him Spanish,” she continued. “She just said, ‘Give me an interpreter.’”

PROBEM offers support classes for two hours a week to migrant students in a few schools in Tijuana as a way to address the trauma that migration has generated.

“It’s really important to work on the children’s self-esteem and acceptance of who they are,” explained Elia Ruth Pérez, the support group’s teacher. “If the kids are doing well, they will be able to learn, overcome themselves and find stability. The language barrier ends up being the least of their worries.”

León, who taught Fleurin last year, sees her fellow colleagues frustrated by the challenges, but she urges them not to shy away from them. “It’s an opportunity not only for the child but for ourselves,” she said.

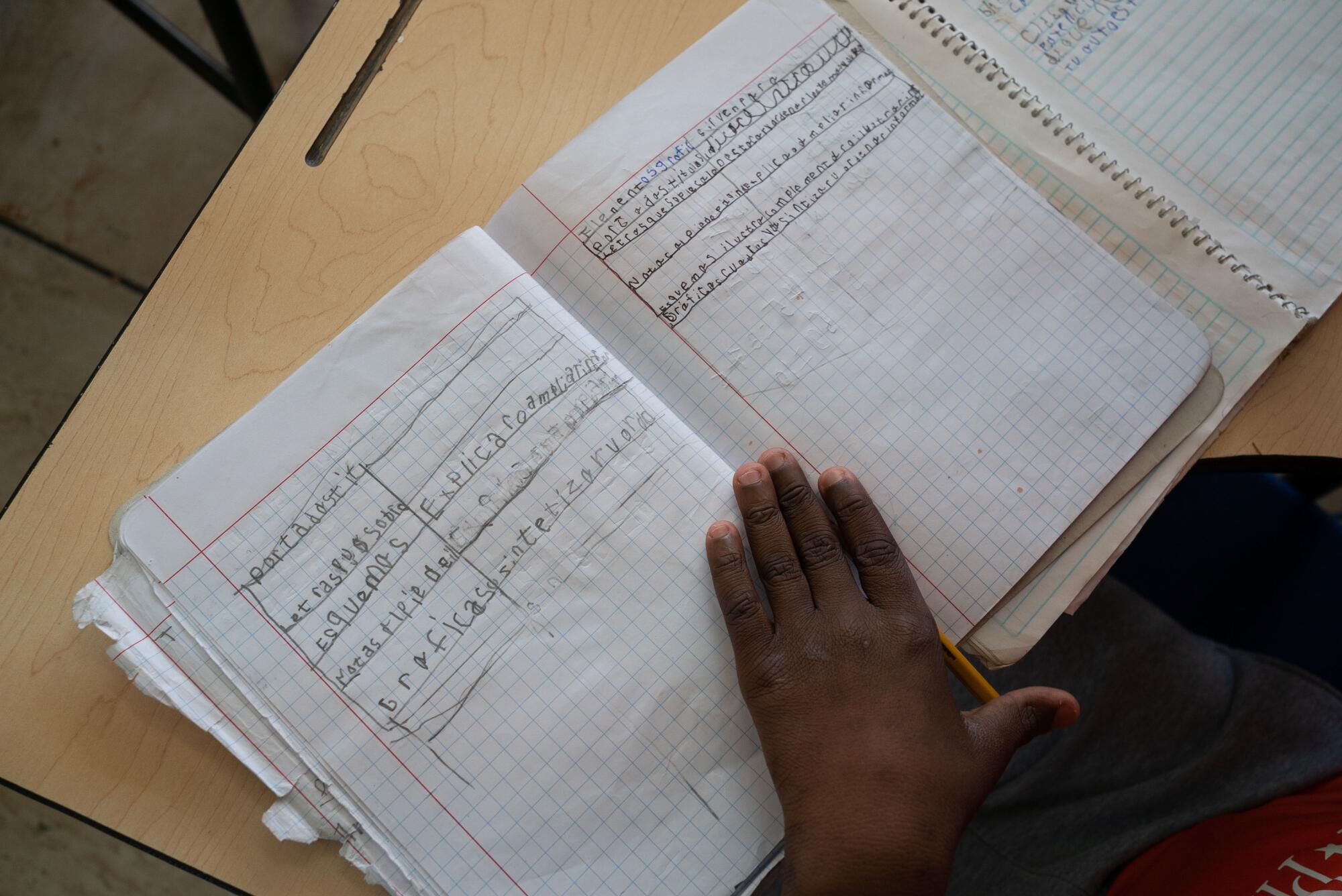

Fleurin has grown since he got to Alba Roja in March 2022. In the few months he spent in León’s class, he made friends and became more organized with his school supplies. He learned how to use his notebook, including where to write down the date, and improved his handwriting.

When he arrived, he didn’t know the numbers in Creole, said León, so they learned them together. She taught him the colors, the numbers up to 50 and simple sums.

Today, in fourth grade, Fleurin usually sits in the back with another Haitian classmate. They speak in hushed Creole, but teachers believe both are learning Spanish quickly. Before the bell rang to let them out on a weekday in December, the boys’ teacher told the class to pick up trash, which the two did without being asked directly.

Still there’s a lot of work to be done. León explained that children often take learning gaps with them to the next grade, as has happened with Fleurin. “Then they don’t want to participate, they feel lost, ashamed or don’t want to go to school anymore,” she said. “It’s like a chain of effects.”

León is afraid this could happen to Fleurin. “If you have a kid from another country who speaks a different language, you can’t ignore it,” she argued, “or you can, but you shouldn’t. You can’t leave everything up to the child.”

At home, Fleurin is a very different child from the quiet boy who stares wide-eyed at his teacher.

One mid-morning in early December, as Fleurin and his sister Dawendjina got ready for school, they started humming Mexico’s national anthem. He laughed and smiled with his sister, making up words as they went along until they stopped and switched to the Haitian anthem, singing it in full force, enunciating each word clearly.

After six years in Tijuana, Fleurin’s father still has his eyes set on the United States and the possibility of a better life for his family. His mother, siblings, aunts and grandchildren in Haiti still depend on him.

“Fleurin is a very hard-working boy; he wants to help me with everything,” said Fletcher. “I only got to primary school, and I want them to go further and become doctors, teachers or pastors.”

Lorena Ríos is a freelance journalist based in Mexico. This story was supported by a reporting fellowship from the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia Journalism School.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.