BUNCETON, Mo. — Gene Ulrich’s gravestone proclaims what he once felt he could never say loudly in life.

But to claim his place in history, up on a hill in this small town notched within America’s Bible Belt, it must be said:

Was the first openly gay mayor elected in the United States of America. Was elected mayor of the City of Bunceton, Missouri April 1, 1980. Served a total of 26 years.

Ulrich might be the most famous gay man you don’t know by name. Also on the gravestone:

Served the United States of America in the Army 1st Cavalry Division in the Republic of Vietnam.

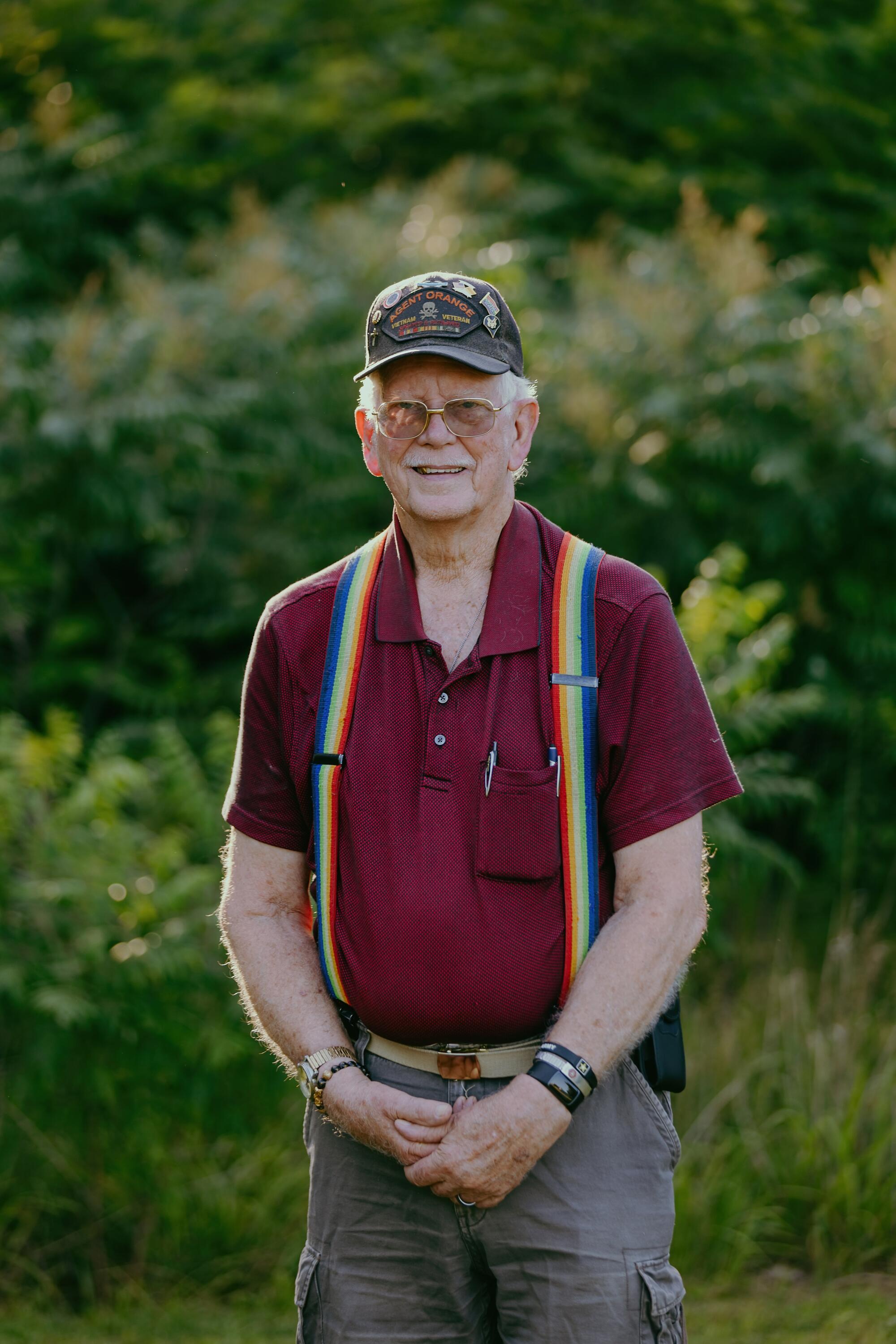

Ulrich will turn 78 in July, and his life bookends the trajectory of gay rights in America. He served in the military before gay people were allowed. He married his partner, Larry Fowler, 43 years before Missouri would recognize it. He adopted a son.

It’s doubtful his name will come up during Pride Month celebrations nationwide, but historians who study LGBTQ rights in the country don’t dispute the headstone’s claim.

In the wake of the Trump presidency, historically marginalized communities are feeling more emboldened to own their identities and document their history. Much of that history centers on big cities, not places such as Bunceton, population around 350.

But Ulrich found he didn’t need to move away to be himself. He grew up on farms, kept his faith in the good Lord and served his country.

There was that time, though, when he ran an adult entertainment store and commissioned the manufacturing of a sex toy in his own anatomical likeness — and sold it under his name.

But Bunceton residents shrugged in the voting booth, reelecting him 12 times in a row. Mayors serve two-year terms in Bunceton. Their annual salary? $3.

So how did he pull it off?

Perhaps that $1.2 million he got in grants to fix up the city helped. Or perhaps townspeople simply remembered Ulrich as someone who grew up alongside them.

“I just lived my life,” he said. “I didn’t hide I was gay, but I didn’t shove it in their face. So people knew what they were getting and that I ran to get good things done.”

In recent years, he watched another former Midwestern mayor — also Christian, also a veteran — mount the first viable presidential bid by an openly queer candidate. Ulrich said he felt astonishment watching Pete Buttigieg kiss his husband, Chasten Buttigieg, when he announced his campaign. And when Buttigieg was sworn in as the first openly gay Cabinet secretary, Ulrich said, he felt a deep personal resonance at the sight of Chasten holding the Bible as Pete swore to defend the Constitution.

According to the LGBTQ Victory Institute, which trains candidates for public office, there are 1,025 openly LGBTQ elected and appointed officials in the U.S.

These days, Ulrich ponders where his place within the arc of queer history may be. Time matters. Diabetes has set in, heart attacks have followed, and he’s been fighting off cancer.

Even how Ulrich sees his own story has changed over the years as society has shifted around him. When the media declared him an “activist,” he shunned the label.

“There were no rainbow flags up at our house,” Ulrich recalled.

Around the time Ulrich became mayor, gay men were being maligned and shunned as the AIDS epidemic spread. Holding public office and living with the man he loved was radical statement enough.

::

A life-changing event happened to Ulrich early on. During a first-grade gym class, a classmate careened into his face, essentially knocking out two teeth.

The family couldn’t afford the dental work, and his mom cried when she found him trying to cut out replacements from a set of toy teeth — the kind worn at Halloween. However, losing those teeth gave Ulrich a sense of resiliency against criticism.

“I didn’t want to be like them,” Ulrich said of bullies he met at school. “But I wasn’t scared off either.”

Later on, the missing teeth provided a good cover for not having to date and confront gay feelings because he felt unattractive.

Even though photo albums show no smile, he grew into a model’s body, 6 feet 2 with a slender build toned by manual labor. His blue eyes were framed by high cheekbones and a defined jawline, all which still whisper out mildly from his face today. His country drawl caramelizes his speech.

Ulrich was in high school when a tractor accident crushed his father’s legs. He would never work again. At 18, Ulrich became the breadwinner for his household of four, quitting school for farm and factory work.

By then the Vietnam War was raging, and in November 1967, a draft notice arrived ordering Ulrich to report for duty. His mom, Geraldine, cut through the exasperated quiet with a suggestion:

“You know, there is a box you can check to get out of it.”

She didn’t elaborate. But she knew. She also knew gay people weren’t allowed in the military.

Ulrich had dated girls but, because of the conservative culture at the time, felt no pressure to have sex or get married. He had a relationship with a man at his factory, but the man refused to come out.

Heartbroken from his lover’s rejection, the 23-year-old Ulrich drove to Kansas City, Mo., for his Army physical. It was the first time he’d ever spent a night away from home.

While filling out paperwork, he saw a box next to a question: Was homosexual or had homosexual tendencies?

“That question reached out and slapped me in the face,” Ulrich recalled. “Mom knows I’m gay.”

Ulrich froze. But he didn’t want to appear indecisive. He didn’t check the box.

While in the Army, one afternoon he was recovering from an illness and stayed in bed. A supply sergeant came, sat on the edge of his bed and started to reach under the covers.

When Ulrich objected, the man said, “Well, you’re not straight.”

“Says who? Get out!”

How did the supply sergeant know? Ulrich wondered about how he looked, how he acted. Did he put his hands on his hips too much? Moreover, he felt violated — and scared.

“I thought it was a trap,” Ulrich said. “I was worried I’d get in trouble.”

Ulrich served a year in Vietnam, returned home in 1969 and worked at various factories for the next three decades.

Over time he saved enough to build a house, albeit in the underserved, Black side of Bunceton where he said he felt more connected culturally as someone marginalized in plain sight. He moved in his aging parents, and they never asked about his personal life.

What’s more, he finally got his two teeth replaced.

::

I thought I was the only one sometimes

— Gene Ulrich

In 1972, Ulrich felt emptiness after his mother died and his sister took in their father. As spring arrived, a new sense of freedom hit him at age 28.

There were no gay bars near Bunceton, nor truck stops or bathhouses, which Ulrich said didn’t interest him.

“I thought I was the only one sometimes,” Ulrich said.

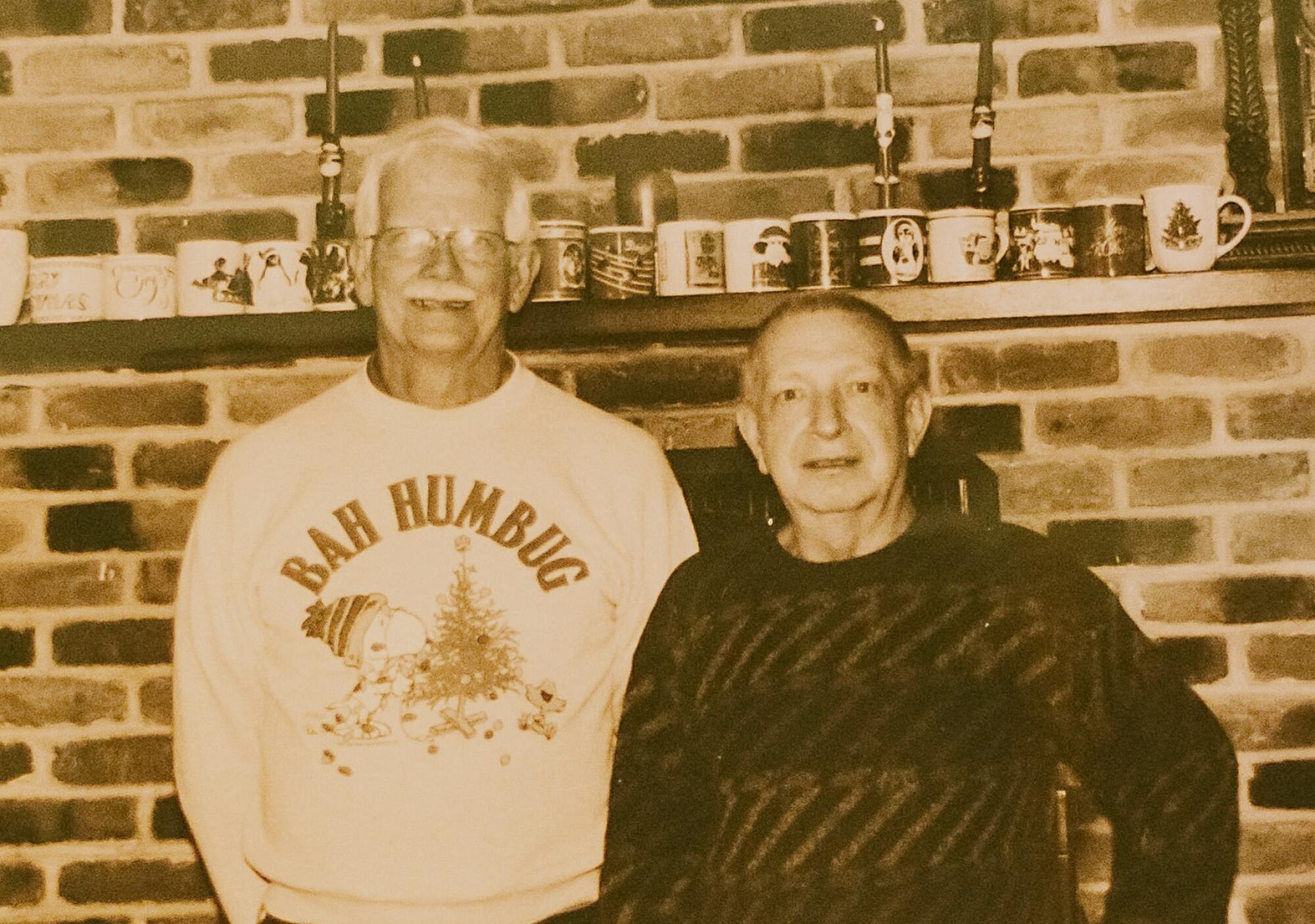

So a friend urged him to place a personal ad in the Advocate, a gay magazine. About seven men replied, nearly all wanting to move in. Except for Larry Fowler.

The 26-year-old hair salon co-owner lived a couple of hours away in Springfield, Mo., and responded with a head shot. It’s now faded into a yellow ghost of an image buried in Ulrich’s wallet. Fowler insisted they get to know each other before they met.

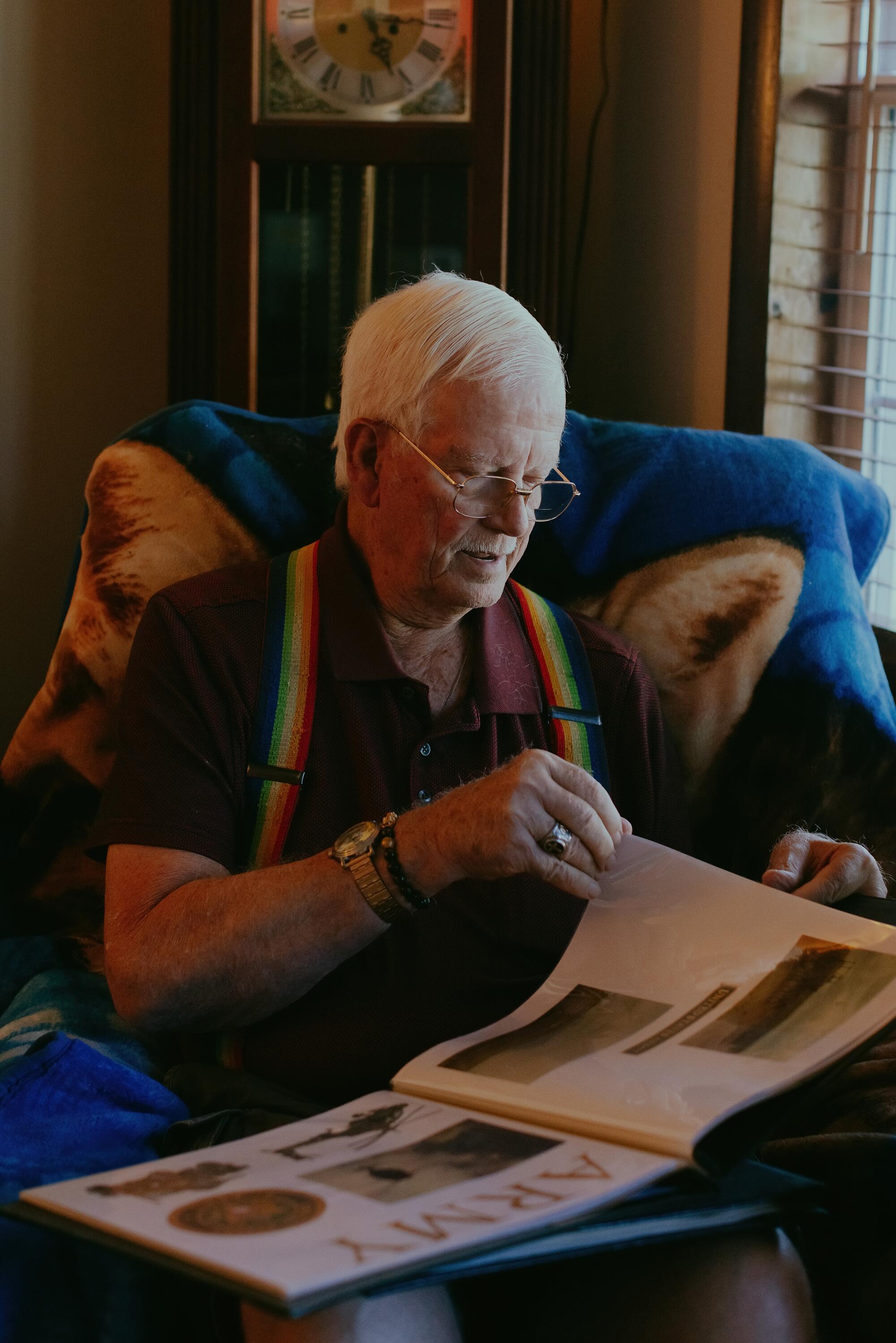

Fowler also served in Vietnam, as a Marine. He never did talk about it much, Ulrich said, but the two would argue over which branch of the military was best.

What followed was a whirlwind romance, and they wrote to each other all summer long, arranging to meet on Labor Day weekend when both would be off work. Just a month later, Fowler sold his share of the hair salon and moved to Bunceton.

By December, they were married in the gay-friendly Metropolitan Community Church.

They didn’t publicly talk about gay rights and could pass just like any other white dudes living in Bunceton.

One day, though, the guard went down. They were in a hardware store when a news report on the store radio said the American Psychiatric Assn. would stop classifying homosexuality as a mental disorder.

Fowler and Ulrich cheered and hugged, drawing surprised stares.

“They must have wondered why we did that,” Ulrich said. “They must have thought we were crazy.”

Fowler didn’t think they should rub their sexuality in others’ faces. Ulrich agreed. And in proper small-town culture, people never brought it up, at least to their faces. So when Ulrich decided to run for mayor, he and Fowler thought it wasn’t so big of a deal.

It wasn’t — at first.

::

Ulrich initially ran unopposed, but just days before the election, the incumbent had a change of heart. On election day, April 1, 1980, Ulrich felt antsy and as soon as he got off work drove to City Hall to watch poll workers and the police chief count the ballots.

He lost by 16 votes.

“I went home thinking I was a loser,” he said.

The next morning, he got a call from a reporter with the nearby Boonville Daily News. “Actually,” the reporter said, “you won by a landslide.”

It turned out his opponent hadn’t filed to run in time and was disqualified.

A few days later, the student newspaper at the University of Missouri got wind that Bunceton had a mayor who might be gay. Ulrich granted an interview, thinking the paper was only distributed on a campus with more liberal attitudes than Bunceton.

Ulrich never felt he had to make a “coming out” speech. But the Columbia Missourian did it for him on May 14, 1980, with a front-page story headlined: “Bunceton Residents Elect Mayor Who Is a Respected Homosexual.”

The media started knocking on Ulrich’s door: the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Associated Press and, later on, a crew from “Nightline.”

Ulrich recalled that on the way home from Bible study the evening the “Nightline” program aired, he and Fowler noticed most homes still had their lights on. Usually, lights went out after the evening news, but people were waiting for “Nightline.”

Gay publications celebrated his election, with the Advocate calling him an “activist” in a profile in 1982.

“Gene’s good people,” resident Kathy Carver told the Advocate. “I like him. They don’t bother nobody.”

Another, John Wright, said, “Hell, no one cares who he sleeps with, ‘long as he don’t mess with no one. They’re married, ain’t they?”

The article quoted Ulrich joking that a nearby town asked him to judge a women’s beauty contest during his first month as mayor: “They said I’d be impartial.”

Later on, a whole chapter was devoted to Ulrich in the 1989 book “In Search of Gay America” by Neil Miller.

The accidental mayor now became the accidental gay icon.

“I didn’t want to be a gay activist,” Ulrich said. “I wanted to make Bunceton better.”

Ulrich spoke at four or five gay pride events over the decades — at one he was hit in the head by a preacher’s hurled Bible — but otherwise, he stayed home.

One news report in the Missourian characterized his speeches as heartfelt “but disappointed those seeking a new poster child for the gay-rights movement. Gene suggested painting houses for the elderly instead of suing for civil rights.” His defense of those speeches then: “Show them we’re human — we do good things; we’re just like anyone else.”

::

For a guy who didn’t feel comfortable publicly reiterating his sexuality, Ulrich’s decision to leave a good-paying factory job to run a porn shop caught many off guard in 2000.

An investor headhunted Ulrich and offered him $10,000 more annually than his management job at a nearby factory.

Ulrich decided to not seek reelection two years later because he’d gone from running the adult entertainment store, First Amendment Video, to owning it.

“But I offered to resign and [the council] said no,” Ulrich said. He won again.

Two years later, Fowler was sick, so Ulrich didn’t want to run again. But a bank teller in Bunceton who handled his finances tricked him into signing a paper that was an application to file for a mayoral run. Then, all the women in the office pitched in to cover the processing fee at City Hall.

He won again.

::

For the record:

12:04 p.m. June 22, 2022In an earlier version of this post, a photo caption said Bunceton, Mo., is 160 miles east of St. Louis. It is west of St. Louis.

Life hasn’t been easy since Ulrich left public office in 2006 to spend more time with Fowler, who was grappling with post-traumatic stress disorder from the war. Within a year, Fowler died in his sleep after suffering a heart attack. Ulrich remembers moving over in bed to feel his cold body.

In 2008, with the recession and trend toward people getting their porn and sex toys online, he closed the adult entertainment store. He worked at a local nonprofit and then ran again for mayor in 2016. This time he got just 32% of the vote.

“Man, I lost in a landslide,” he said.

If voters interviewed outside City Hall on that 2016 election day offer any insight, his age and the public’s short-term memory contributed more to his loss than his sexuality.

Rachel Emde, then a college student, said, “Honestly, I don’t think many people know him that well.”

Ulrich thinks she’s right.

“I feel sort of forgotten,” Ulrich said. “Maybe it’s because I didn’t have a tragic ending.”

Indeed, most mainstream portrayals of trailblazing gay men in Ulrich’s lifetime didn’t end well.

Marc Robert Stein, a history professor at San Francisco State University, mentioned Ulrich briefly in his book, “Rethinking the Gay and Lesbian Movement.”

“I don’t think he should be considered a gay activist,” Stein said. “But his story is important because it redefines what we tend to think of the LGBT movement as mostly being in San Francisco or New York. His election should be seen as not just as a need to redefine how we see LGBT history, but American history.”

::

On a winter morning, he brushed off dirt from a ceramic lighthouse next to the pink granite headstone he’ll share with Fowler one day. “Feels weird to be the only one here now,” Ulrich said

Every day, Ulrich visits his family’s cluster of graves in the town’s Masonic cemetery. He kissed his hand and placed it on each grave.

Ulrich isn’t totally alone, a fact that shows how gay people create chosen family.

In 2013, Ulrich adopted Chris Anderson, now in his mid-40s, whom he and Fowler helped raise as a teenager when he showed up to work at Ulrich’s factory after a tumultuous childhood. Anderson lives a couple of hours away but sees him at least weekly and he worries about Ulrich dying alone.

Ulrich, however, already has come to terms with the inevitable and, as a planner, even laid out his funeral itinerary.

He already has his casket, knows what Christian hymns will play, and wants to be buried nude aside from a purple satin sheet to cover his body. (“I came into the world that way and so plan to go the same way.”) He’s hired a DJ for the wake and wants his favorite party song, the Village People’s “Y.M.C.A.”

To be placed inside his casket: his crucifix, ashes of his three cats — Fuzzle, Ms. Gwen and Tripod — and the sex toy in his likeness, because “you never know if you’ll need it,” he says with a laugh.

At the cemetery, he looked at the headstone that a local gay community group bought him in 2015 because its members worried he wouldn’t be given his flowers noting his history-making election before dying.

Ulrich instead mostly ponders what date will appear in that blank space under his birth date because “that’ll be the day I hopefully get to finally see Larry again.”

He knows he is but a footnote in U.S. history. But at least at his grave, on that stone atop that hill of where he calls home, his place will be noted for all to see when that time comes.

Vara-Orta is a special correspondent.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.