With Russians gone, Kyiv’s suburbs struggle to return to being ‘a happy place’

BORODYANKA, Ukraine — The soccer mom parks her car just past the charred ruins of the town cultural center, a hollow, bombed-out remnant of better times. Her son bounds out toward the green fields freshly daubed with white boundary lines.

“He and I lived through it all together,” says Valentyna Shleyuk, 32, gesturing toward her son, Artemi, 9, now scampering to join other youths on the spruced-up playing field. “The bombings, the occupation, the destruction. We were hiding all the time in the basement. He understood what was happening. But he always wanted to come out to play.”

In the mostly abandoned town of Borodyanka, where Russian bombs, shelling and battles hammered rows of Soviet-era apartment blocks, the seemingly mundane sight of kids kicking balls on a neatly groomed pitch counts as a jarring moment. The hard-hit towns outside of Kyiv are having a difficult time returning to any sense of normality.

It has been almost three months since Russian forces launched their invasion, occupying the outskirts of Kyiv, the Ukrainian capital, before retreating after meeting unexpectedly fierce resistance during a monthlong occupation. President Vladimir Putin’s expectations of a lightning advance to seize the venerable capital ended with boneyards of Russian war materiel scattered across the landscape. Moscow has since turned its military might to the east and south, where the war still rages.

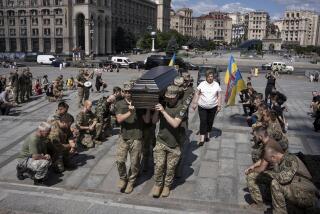

It is calm these days in Kyiv and its suburbs. Stricken Russian war machines have largely been cleared from the roads, along with the civilian vehicles obliterated in hails of gunfire. And the dead whose remains littered streets or were buried in makeshift graves have mostly been given proper funerals, often after forensic examinations for possible war crimes. While unexploded ordnance remains a threat, Ukrainian military teams have cleared major thoroughfares of mines, shells and other lethal detritus.

In the capital itself, which Russian ground forces failed to penetrate, a sense of normality has returned with the spring weather, despite a cautionary nightly curfew and frequent air-raid sirens. Authorities say about two-thirds of Kyiv’s 3.5 million residents are now back in a city that saw a mass exodus in the days after the Russians invaded Feb. 24.

But in towns outside Kyiv — places like Borodyanka, Bucha and Irpin, all northwest of the capital, once the front line of Moscow’s ill-fated offensive — the return to routine remains halting at best. Only a fraction of the prewar population has come back. Most remain elsewhere in Ukraine or Europe, among the 14 million Ukrainians — more than one-quarter of the population — who have fled their homes, marking Europe’s greatest refugee crisis since World War II.

The Russian legacy of bombed-out and bullet-riddled homes and businesses seems incongruous in an otherwise tranquil zone where pine forests, lakes and ponds intersect with the land.

“This used to be a happy place — there was a bowling alley, cafes, a movie theater,” said Serhii Gachkov, 35, who ran a mall called Giraffe in Irpin, just northwest of the Kyiv city limits, and the former site of intense firefights.

He picked a few bullet cartridges from the vast expanse of rubble at the former commercial plaza. On his cellphone, Gachkov showed a reporter images of the center while it was still a thriving gathering space. His archive then shifted to scenes of Ukrainian troops dug in defensive positions in and around the mall, as the Russians attacked.

“This was a place for kids, for young people,” said Gachkov, still seemingly in disbelief at the destruction. “More than 300 people worked here. Now it’s all gone. There’s no way to bring it back. This will all have to be demolished.”

To the northwest of Irpin lies the city of Bucha, a leafy Kyiv bedroom community that became infamous for alleged Russian atrocities. Images of bodies on the streets were the first large-scale public indication of war crimes allegedly committed during the Russian occupation of the greater Kyiv region.

Authorities say as many as 400 civilians were killed in Bucha. Rows of fresh graves, many with Ukrainian flags, mark the city cemetery. Officials say some 1,000 civilians lost their lives in the Kyiv suburbs during the Russian onslaught and occupation.

In addition, more than 1,300 buildings were damaged in Bucha. Initial estimates put the cost at almost $500 million. It is unclear how much public funding will be available for widespread reconstruction in a nation where warfare has wreaked havoc on the economy.

“We all survived, but our apartment is destroyed, no one can live there,” said Dovzhenko Andrii, 38, on a recent afternoon in front of his shell-pocked Bucha apartment complex, the target of Russian artillery and gunfire.

A shell hit his eighth-floor flat just moments after his wife had left, he said. The complex of some 500 units remains mostly empty, as Ukrainian war-crimes prosecutors, aided by a French forensic team, examine the damage, tracking the trajectory of Russian fire.

Parked out front were a dozen or so bullet-riddled vehicles, including Andrii’s blue Citroen sedan. He and a friend were wrapping the car in plastic to protect it from the elements, though the battered Citroen seems destined for the junkyard.

Residents have been trickling back to Bucha as the city works to restore electricity, water, gas and other services.

“People have to know that it is safe, and that they will have a certain level of comfort, before they return,” said Mykhailyna Skoryk, an advisor to Bucha’s mayor, in an interview at her office.

Another factor: a sense that Russia could return.

“Some people have a psychological fear that the Russians are going to come back,” said Yerevan, 32, a Territorial Defense Forces fighter in Makariv, a town west of Bucha that remains largely deserted.

“People are afraid of that,” added Yerevan, who declined to give his surname for security reasons.

Most large stores and schools remain closed in Bucha and other hard-hit communities. Residents were lining up at a butcher shop in Bucha on a recent afternoon after word spread of a delivery of fresh meat.

Down the street, Inna Verzylova, 53, and her son, Bulat, were hawking vegetables and fruit from a makeshift stand. Their apartment was shelled; they are living in the home of a neighbor who has left town. But the produce sales are the source of some income to defray expenses, including repairs on their home.

“People are happy to have a chance to buy something fresh,” said Verzylova, as she greeted customers. “There’s not much margin for profit. But we also feel we are contributing to bringing our community back.”

About 20 miles to the northwest, the town of Borodyanka is among the worst hit — and shows no sign of coming back anytime soon. The agricultural hub of about 12,000 was a key strategic objective for Russian forces en route to the capital. Residents say Russian war planes attacked without warning March 1, hitting a number of the aging apartment buildings.

Soon, Russian troops and tanks pushed out Ukrainian defenders. The occupiers billeted at a local restaurant, Sashy, where Russian boots, military garb and ration boxes are still scattered about.

Residents say there has been little outside help, beyond the clearing of debris and unspent munitions.

On a recent morning, Denis Alyoshyn, 41, was scouring the family’s smashed first-floor apartment for furniture and other salvageable items. Seven people were killed in the building when the Russians bombed the place March 1, residents said.

“There’s really not much left that we can use,” said Alyoshyn, after lugging a dust-covered bookcase out of the flat, climbing through a window to exit.

The family has bigger worries. His wife, Oksana, 39, lost her right leg in the bombing. Their son, Vlad, 22, probably saved his mother’s life by fashioning a tourniquet out of a curtain to stanch the bleeding until the family could find a car amid the chaos to take her to the hospital.

Also picking through the ruins was a desperate Maria Vasylenko, 77. She said she was seeking vital documents for her daughter, Alyona Khuhro, 41, who, along with her husband, were among the seven killed in the Russian attack. She said she needed the papers to apply for government compensation for her daughter’s two children, ages 16 and 10, who are in Poland with relatives. She said the family has not yet had the heart to inform the children of their parents’ fate.

On May 16, Vasylenko said, her granddaughter celebrated her 10th birthday in Poland. The girl wondered why her parents didn’t call.

“I had to tell her that her mother is helping at the front line,” Vasylenko said, noting that her daughter was a nurse. “And that her father is defending his country” as a soldier.

She seemed to have no luck finding the documents.

Outside the vacant town hall, down the street from the burned-out police station, a V for Victory sign painted by Russians defaces a billboard featuring images of Borodyanka residents — among them a teacher, a bus driver, a welder and a wrestling trainer.

In a central square, a bronze bust of Taras Shevchenko, a much-beloved 19th century Ukrainian poet and nationalist, is slumped over. Holes from shrapnel or bullets scar the monument.

Many buildings in Borodyanka will probably have to be torn down, so extensive is the damage.

Yet over at the soccer field, as residents picked through debris seeking vestiges of former lives, Artemi and the other kids were kicking a ball around the newly seeded grass, seemingly a world away from the calamity that has sown chaos in so many once-quiet towns.

“Soccer gives him some respite,” says Shleyuk, Artemi’s mother, as she watches her son and others running about. “The kids around here really need that. Especially now.”

Special correspondent Liliana Nieto del Río in Borodyanka contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.