Young Ukrainian designer puts his stamp on the country’s war effort

LVIV, Ukraine — One of the most iconic episodes of the nearly 12-week-old war in Ukraine took place in its first few hours, when the crew of a massive Russian missile cruiser demanded the surrender of a small contingent of Ukrainian troops stationed on Snake Island, a rocky Black Sea outcropping measuring less than a square mile.

In a radio transmission that subsequently went viral, one of the defenders delivered a pungently profane response that has been most commonly translated as: “Russian warship, go f— yourself.”

Coming at a moment when much of the world expected Ukraine’s swift collapse in the face of invasion by its larger neighbor, the raunchy, almost jaunty expression of defiance helped power the underdog narrative that has proved invaluable to the country’s war effort.

It also brought unexpected fame to the young Ukrainian illustrator who designed a wildly sought-after postage stamp commemorating the event.

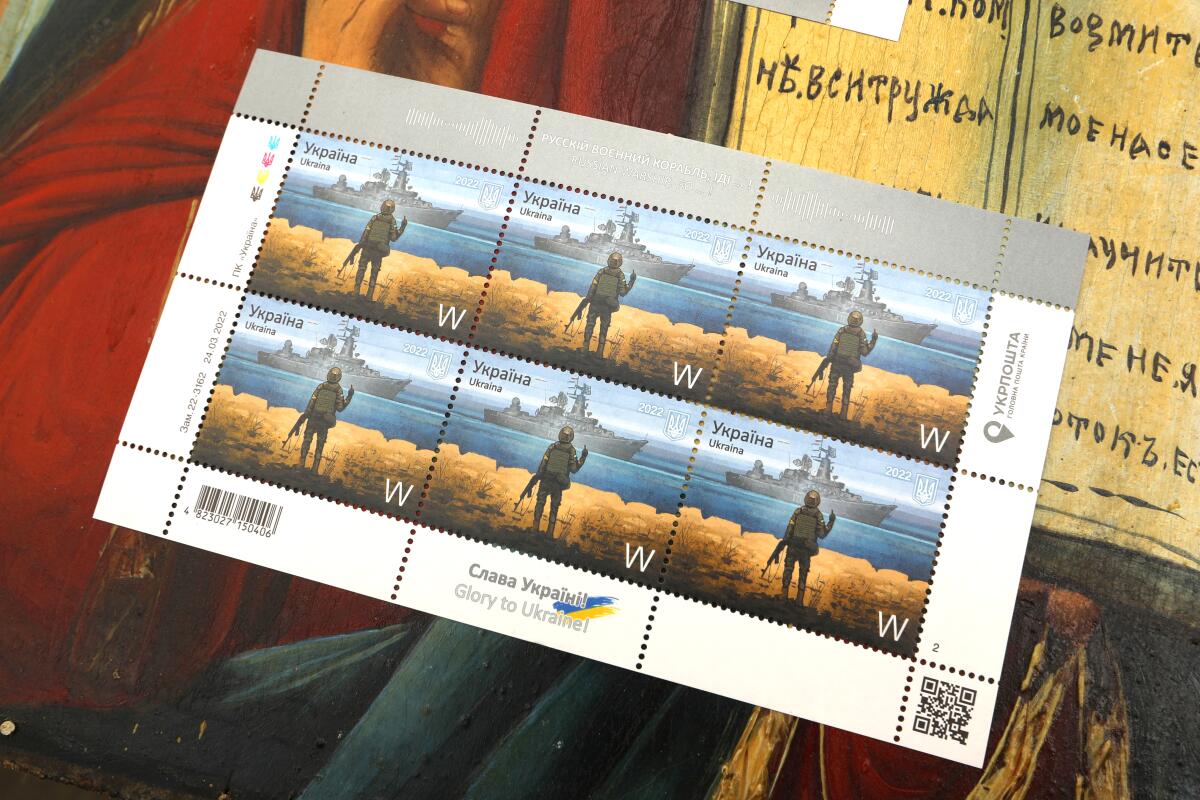

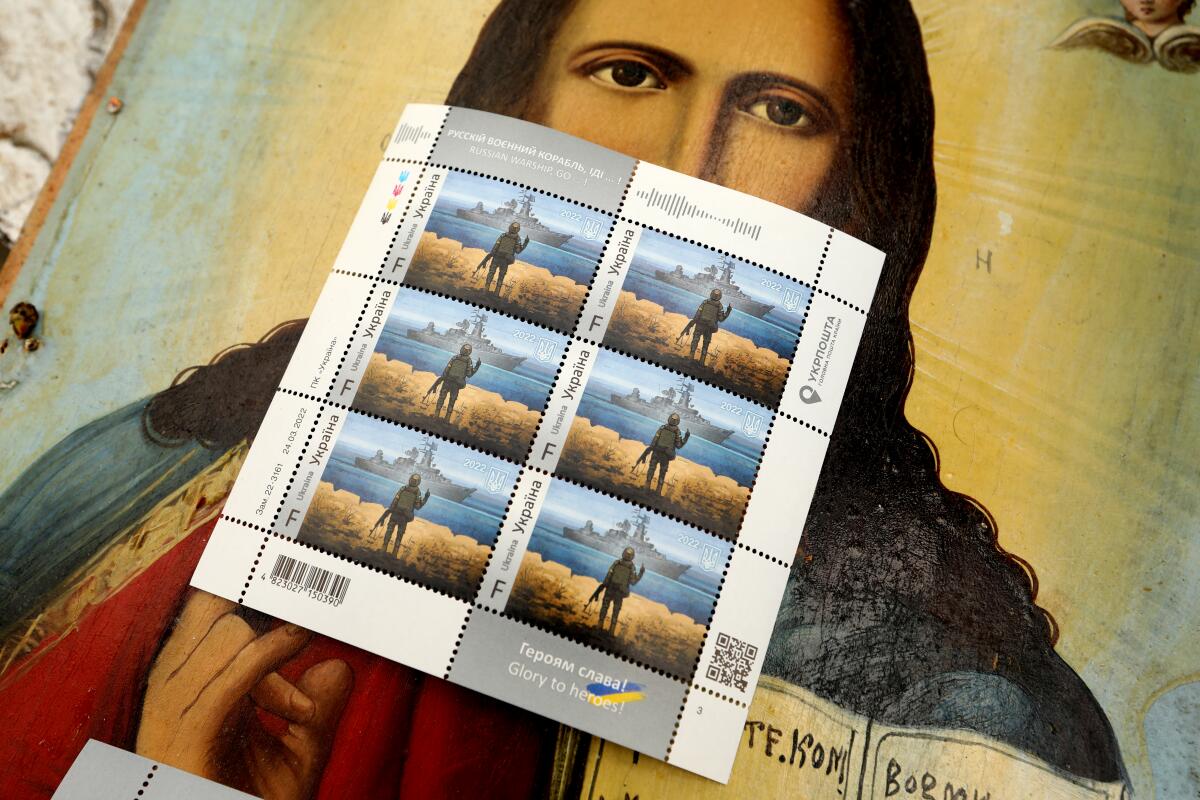

Released on April 24, the stamps were greeted with enormous lines at the post office, punctuated by the occasional scuffle between would-be buyers. The initial series became a valuable collector’s item. The national post office, Ukrposhta, had a million of the stamps printed, and they remain in heavy demand.

“I never thought it would be so popular,” said artist-designer Boris Groh, 27, who lives and works here. He moved first to the capital and then to Lviv after his education and upbringing in Crimea, the peninsula seized by Russia in 2014.

Like so many of his compatriots, he was left goggle-eyed by a dramatic twist in the story that occurred weeks after he created his design, just 10 days before the stamp was released. The menacing warship, which turned out to be the Moskva, the flagship of Russia’s Black Sea fleet, was sunk by a Ukrainian missile attack that Moscow has never acknowledged.

“It was … well, it certainly turned out to be good marketing for the stamp,” said Groh, who has a bashful demeanor and a classic young-artist mien: tall and thin, with floppy hair and jutting cheekbones, long slender fingers and a flowing overcoat.

Even before the stamp, the art-school-educated Groh was building a reputation for illustrations that included album covers for the classical-metal musical collective Lost Symphony. He entered the post office’s design competition on a whim, and said he spent perhaps five hours over several days on a stylus-drawn digital composition featuring a lone figure in the foreground, middle finger raised, and the silhouette of a hulking warship offshore.

“Like everybody, I was pretty distracted by the news at the time,” he said.

The vulgarity of the figure’s gesture was meant to convey the spirit of the coarser language employed in the real-life episode, which is alluded to with tiny lettering along the stamp’s perforated edge: “Russian warship, go…”

Everyone knows the rest.

After the sinking, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, a professional comic before turning to politics, alluded to the defiant obscenity without actually uttering it. In a video address after Western analysts and officials backed up the Ukrainian account of a missile strike on the vessel, he cited proof that “Russian warships go” — strategic pause — “to the bottom of the sea.”

Groh, whose work tends toward the melancholic and dystopian, said he set out to create an image that would reflect the David-versus-Goliath ethos that has infused the conflict, galvanizing international condemnation of Russia.

“I wanted it to be artistic, but also faithful to life. I started research on the ship, learned about the Moskva’s dimensions and profile. I wanted the image of a small person set against this big unknown enemy, facing down a giant.”

In depicting the shore and the sea, he incorporated the colors of the Ukrainian flag, yellow and blue.

The story of Snake Island and the Moskva has unfolded in chapters that continue today. The Ukrainian soldiers on the island were at first reported to have all been killed in the Russian assault, but some were instead captured and later freed in a prisoner swap.

Russia remains in control of the island, and the Institute for the Study of War, a Washington think tank monitoring the fighting, says Moscow is using the strategic dot of land to try to “block Ukrainian maritime communications and capabilities” in the area, especially the approach to the principal Black Sea port of Odesa.

Ukraine claimed this month to have used an armed drone to destroy another Russian vessel near Snake Island, this one a Serna-class landing craft. The Ukrainian defense ministry also said a Russian missile-defense system on the island was hit.

The Moskva’s sinking also featured in the controversial leaked disclosure earlier this month that the United States had provided intelligence that aided in the Ukrainian missile attack on the ship. Amid worries of Washington drifting toward direct conflict with Moscow, the Pentagon stressed it had not given Ukrainian forces “specific targeting information,” and President Biden issued a sharp warning to intelligence chiefs about leaks that could be read as braggadocio or unwarranted provocation of Russian President Vladimir Putin, or both.

The Moskva had a crew of about 500, and the fate of the crew remains largely unknown, although many are thought to have been killed in the missile strike and a huge resulting fire aboard. After the sinking, Russia released video depicting what seemed to be a large number of surviving crew members, but reports have circulated that at least some of the Russian sailors shown in the footage have failed to make contact with their families, suggesting that the video may have been shot before the ship was lost.

While the Moskva and Snake Island are now part of Ukraine’s national lore, Zelensky, among others, has offered a modicum of caution about mythologizing wartime events, even as a means of boosting morale in a country scarred by the invasion’s toll of death and displacement.

The battle, he warned, would have its ups and downs. In a recent address, the president urged compatriots, “especially those in the rear, not to spread excessive emotions,” adding: “We shouldn’t create an atmosphere of specific moral pressure, when certain victories are expected weekly and even daily.”

Still, the theme of improbable victory is a powerful one. The West has rallied to Ukraine’s support, pumping billions of dollars in aid and weaponry into what had previously been something of a backwater on Europe’s eastern fringe. But U.S. and European officials and analysts also warn that the war could devolve into a grinding, bloody and protracted struggle.

In the meantime, displays of spontaneous patriotism abound. Flags flutter from homes and businesses. When street musicians launch into an up-tempo version of the national anthem, young and old in the crowd sing unabashedly along. Old Ukrainian poetry that people last heard in elementary school is repurposed in rap songs. Upscale clothing stores display racks of jackets, dresses and trousers color-coded in blue and yellow.

And the post office is about to commemorate the Moskva’s fate again, with a new stamp to be released this week, depicting the warship submerging, bow up, Titanic-style. It plans a run of 5 million, with purchase of the stamps to be available online internationally.

As for Groh, he is out of the stamp-design business, but is proud of his work. His pay from the post office, he said, was only “symbolic,” but he retains ownership of his image.

In Ukraine’s currency, a sheet of six stamps, war-themed or otherwise, sells for 44 hryvnia, about $1.50, for international postage and 23 hryvnia, around 78 cents, for domestic mailing. On a recent weekend, an antiquities dealer in Lviv’s biggest open-air market was selling sheets from the original run of the Groh-designed stamp for about $250.

With what he hopes will be a long artistic career ahead of him, Groh says his main thoughts of the future center on when the war will end.

“I was happy to help, as a Ukrainian citizen,” he said. “About what happened with Snake Island, with the Moskva, I just felt what we all felt.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.