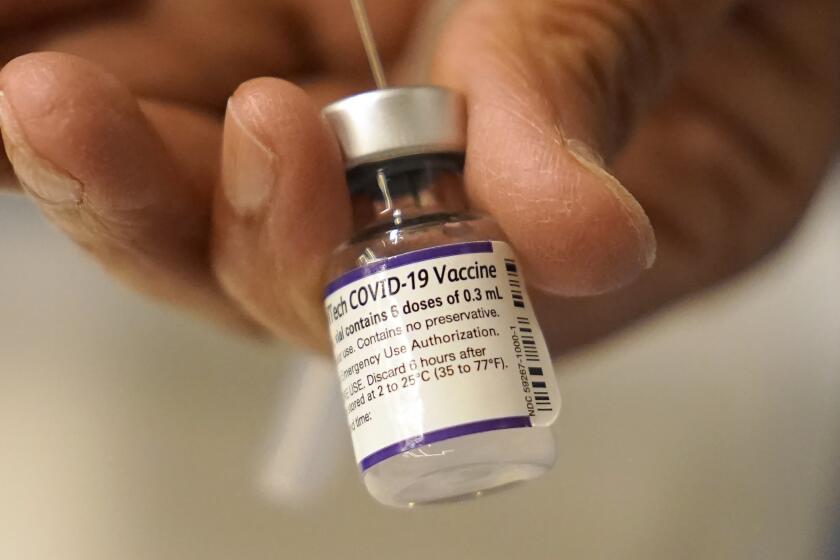

U.S. expands Pfizer COVID-19 booster for 16- and 17-year-olds

U.S. health authorities said Thursday that 16- and 17-year-olds should get a booster dose of Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine once they’re six months past their last shot.

The U.S. and many other nations already were urging adults to get booster shots to pump up immunity that can wane months after vaccination, calls that intensified with the discovery of the worrisome new Omicron variant.

On Thursday, the Food and Drug Administration gave emergency authorization for 16- and 17-year-olds to get a third dose of the vaccine made by Pfizer and its partner BioNTech. And hours later, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention lifted the last barrier — saying those teens should get their booster as soon as it’s time.

Boosters are important considering that protection against infection wanes over time and that “we’re facing a variant that has the potential to require more immunity to be protected,” Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the CDC, told the Associated Press.

About 200 million Americans are fully vaccinated, including about 4.7 million 16- and 17-year-olds, many of whom got their first shots in the spring and would be eligible for a booster.

Pfizer says a booster dose of its COVID-19 vaccine may protect against the new Omicron variant, which early indications show might be more contagious.

“Vaccination and getting a booster when eligible, along with other preventive measures like masking and avoiding large crowds and poorly ventilated spaces, remain our most effective methods for fighting COVID-19,” Dr. Janet Woodcock, acting FDA commissioner, said in a statement.

The Pfizer vaccine is the only option in the U.S. for anyone younger than 18, either for initial vaccination or for use as a booster. It’s not yet clear if or when teens younger than 16 might need a third Pfizer dose. But Walensky said the CDC and FDA would closely watch data on 12- to 15-year-olds because if they eventually need boosters, “we again will want to act swiftly.”

Vaccinations for children as young as 5 began last month, using special low-dose Pfizer shots. By this week, about 5 million 5- to 11-year-olds had gotten a first dose.

The extra-contagious Delta variant is causing nearly all COVID-19 infections in the U.S., and in much of the world. It’s not yet clear how vaccines will hold up against the new and markedly different Omicron mutant. But there’s strong evidence that boosters offer a jump in protection against Delta-caused infections, currently the biggest threat.

In a large study, the risk of a breakthrough infection was 10 times lower for people who got a COVID-19 booster shot than for people who hadn’t.

“The booster vaccination increases the level of immunity and dramatically improves protection against COVID-19 in all age groups studied so far,” BioNTech Chief Executive Ugur Sahin said in a statement.

Complicating the decision to extend boosters to 16- and 17-year-olds is that the Pfizer shot — and a similar vaccine made by Moderna — have been linked to a rare side effect. Called myocarditis, it’s a type of heart inflammation seen mostly in younger men and teen boys.

The FDA said rising COVID-19 cases in the U.S. mean the benefits of boosters greatly outweighed the potential risk from the rare side effect, especially as the coronavirus itself can cause more serious heart inflammation.

Health officials in Israel, which already gives boosters to teens, have said the side effect continues to be rare with third doses.

A U.S. study this week offered additional reassurance. Researchers from children’s hospitals around the country checked medical records and found the rare side effect usually is mild and people recover quickly. The research was published Monday in the journal Circulation.

Associated Press writer Matthew Perrone contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.