How an American in Paris won the rarest of French honors

- Share via

PARIS — Laurent Kupferman has been obsessed with Josephine Baker for nearly a decade, reading everything he could about a woman whose life story was so improbable, so American and yet so French.

For the record:

2:35 p.m. Dec. 1, 2021An earlier version of this article incorrectly reported that U.S.-born entertainer Josephine Baker said the song “J’ai Deux Amours” was an homage to her “two loves,” Paris and Manhattan. The song’s lyrics refer to “mon pays et Paris” — “my country and Paris.”

She was a Black entertainer who escaped American racism in the 1920s by moving to Paris, the one place she felt free to make history in pushing the boundaries of art and advocacy. The singer and dancer even helped France fight the Nazis.

This year, Kupferman began to think that his country — and the rest of the world — needed Baker as much as he did.

“Racism is very high. Antisemitism is very high. Hate is very high,” said Kupferman, 55, who is an essayist and public relations professional for an autism advocacy group in Paris. “And she was fighting against that. And she did it with her art.”

Kupferman in April revived an effort to win Baker, who died in 1975, the rarest of French honors — enshrinement in the Pantheon in Paris. On Tuesday, Baker will become the 81st person to be buried or enshrined in the 18th century monument dedicated to honoring the French ideals of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Plans are underway to reinter the remains of American-born singer and dancer Josephine Baker at the Panthéon monument in Paris.

Contrary to some media reports, she will not be reinterred in the Pantheon but rather memorialized with a cenotaph containing soil from various places where she lived. Baker will be just the sixth woman, first woman of color and first American-born person to join the likes of Marie Curie, Victor Hugo, Emile Zola and Voltaire.

Kupferman was not the first person to propose this honor for Baker, but his endeavor quickly succeeded where others had failed. As he made the case for Baker’s healing power, he would learn he had a surprising and powerful backer, one who had the authority to honor Baker and had grown up listening with his grandmother to the warbling jazz singer’s records.

The effort also landed at a moment when France, like the United States, has been wrestling with questions of racial identity and how it has acknowledged the contributions of influential people of color. The Black Lives Matter movement and the 2016 death of a Black man in police custody in a Paris suburb sparked protests here, along with increasing questions about whether France’s officially colorblind philosophy of universalism masks the reality of racism and religious discrimination.

“France’s recognition of Blackness always seems to be trying to send the message that it is not the United States,” said Annette Joseph-Gabriel, author of “Reimagining Liberation: How Black Women Transformed Citizenship in the French Empire.”

Ellen Garrison Jackson Clark, the daughter of a runaway slave, was a 19th century Rosa Parks, an early civil rights activist whose work was largely forgotten. Then historians discovered she was buried in an unmarked grave in Altadena.

“The reality is complex,” she said. “It is at once the reality of racial discrimination, the legacy of French colonialism but also the promise of French universalism.”

‘J’ai Deux Amours’

The Pantheon idea was seeded in 2013 when Kupferman stumbled across a column in Le Monde, the French newspaper, arguing for Baker’s enshrinement.

He had grown up with Baker as many French do, humming the song “J’ai Deux Amours,” her famous homage to her “two loves” — her country and Paris.

But as he read biographies and looked up old film clips, he began thinking about her potential to rekindle “the light” of idealism that spawned France and the United States, the two great republics born in the 18th century.

“I must say I’m in love with her,” he said. “It’s not real, but I admire her.”

He learned that Baker, born in 1906, grew up fatherless in St. Louis and became a professional dancer in her teens, eventually making her way to New York, where she sang and danced at Harlem theaters and Manhattan’s famous Plantation Club.

Baker jumped at a chance to sail to Europe to join a Paris cabaret show, a move that she later described as her best chance to escape the dangers of being Black in America. She “ran away from home,” Baker told an audience in St. Louis in 1952. “I ran away from [here], and then I ran away from the United States of America, because of that terror of discrimination, that horrible beast which paralyzes one’s very soul and body.”

When Baker arrived at the Paris train station in 1925, a white man helped her off the train and smiled at her. According to Kupferman, she said, “It was the first time I felt like I was treated as a person and not as a color.”

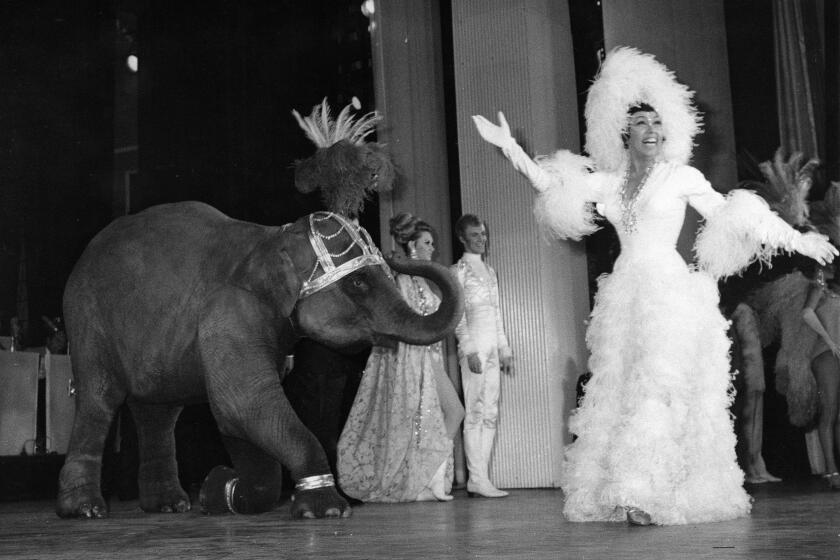

She became a French celebrity who danced in risque cabarets, inspiring Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso and other artists who made Paris a symbol of culture and freedom after World War I. She wore scanty costumes and later sang with an openness that embodied the French ethos of liberty.

“She was Madonna before Madonna,” said Brian Scott Bagley, an American dancer who moved to Paris 14 years ago to choreograph a show about Baker and has since become a leading collector of Baker-related artifacts. He added: “The Beyonces and the Rihannas and everybodies” all owe a debt to her.

Baker married a white Jewish man as fascism spread across Europe in the late 1930s and, after their separation, helped smuggle him and his family out of the country to escape the Holocaust. She became a French citizen, joined the Resistance, charmed Nazis and stole their secrets on the way to winning medals and admiration of the French people.

Like many figures of her day, Baker left a legacy that is both nuanced and complex. She performed the “banana dance” and the “savage dance,” wearing feathers on her body, and walked down the Champs-Élysées with a pet cheetah to promote her shows, which portrayed her as a sexual, primitive and exotic product of the jungle — reinforcing many of the era’s ugly stereotypes.

She also broke sexual taboos by having affairs with women, and she took jabs at the political order by performing in Fidel Castro’s Cuba.

She adopted a dozen children from around the world — a “rainbow tribe” — to live in a utopian village she built around her castle. Then, when her money ran out and she was forced to auction off the castle, she lived in a villa in Monaco at the invitation of Princess Grace, the former movie star who had become a friend. Baker spent her final years in Monaco and was buried there.

Though she fled America, it was never far from her thoughts, and she returned to her homeland frequently to fight American segregation laws, and she canceled appearances in whites-only venues. She spoke alongside the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. at the March on Washington, one of only two women who addressed the crowd that day.

“I have walked into the palaces of kings and queens and into the houses of presidents,” she said. “And much more. But I could not walk into a hotel in America and get a cup of coffee, and that made me mad.”

‘Like in a dream’

A year into the COVID-19 pandemic, when the world was full of gloom, Kupferman contacted one of Baker’s sons and said he wanted to relaunch an online petition he had started in 2019 to get Baker into the Pantheon. By then, there were a handful of others on his team, including a prominent French academic and, later, a singer-songwriter named Laurent Voulzy.

They persuaded a radio station, France Musique, to interview them about the proposal. A few days after airing the interview, the station played a day of Baker’s music.

Media attention grew and signatures mounted to nearly 40,000.

French President Emmanuel Macron has announced that psychology appointments in France will be funded by the government starting next year.

Within a month, a surprise came: An advisor to President Emmanuel Macron invited the group to a meeting at the Elysée Palace. As they were wrapping up, Brigitte Macron, France’s first lady, popped her head into the room to ask how things were going.

The men stood up to salute her.

She apologized that her husband was in Brussels, while explaining that he grew up listening to Baker’s music with his grandmother.

“He knows your mother’s songs better than me,” she told Brian Bouillon-Baker, a 65-year-old actor who is Baker’s seventh son and serves as a family spokesperson.

As they toured the palace, the first lady confided that a decision had already been made by Macron, the ultimate authority on such matters: Baker would join the Pantheon.

“We were like in a dream” Bouillon-Baker recalled.

Kupferman was excited but worried about getting ahead of himself.

“It was 98%, but not 100%,” he said.

Brigitte Macron added, however, that they were to keep it a secret until they had a chance to meet with President Macron and he could make the announcement himself.

The meeting with the president came in July, and Kupferman and the others spelled out their case with details about Baker’s life and how it embodied the ideals of French universalism, a country she described in 1952 as enjoying “true freedom, democracy, equality and fraternity.”

Near the end of the hourlong meeting, Macron gave Bouillion-Baker a wink of affirmation and told him, the son recalled, “Your mother will be in the Pantheon for all the services she has given to France, but not only to France.”

In recognition of Baker’s global influence, her cenotaph at the Pantheon will contain soil from Paris, Monaco, St. Louis and the Dordogne region in southwest France, where she lived much of her life. Her enshrinement, announced by Macron in August, will also not be the first time she will have been honored by a president. In 1963, as she joined thousands for the March on Washington, she told the crowd she had just been handed an invitation to meet President Kennedy at the White House.

“I am greatly honored,” she said. “But I must tell you that a colored woman — or, as you say it here in America, a Black woman — is not going there. It is a woman. It is Josephine Baker.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.