Iran’s new hard-line president-elect says he won’t meet with Biden

DUBAI, United Arab Emirates — Iran’s president-elect said Monday that he would not meet with President Biden or negotiate over Tehran’s ballistic missile program and its support of regional militias, sticking to a hard-line position following his landslide victory in last week’s election.

Judiciary chief Ebrahim Raisi also described himself as a “defender of human rights” when asked about his involvement in the 1988 mass execution of some 5,000 people in Iran. It marked the first time he’s been put on the spot on live television over that dark moment in Iranian history at the end of the Iran-Iraq war.

As for the Biden administration, “the U.S. is obliged to lift all oppressive sanctions against Iran,” Raisi said at a news conference in Tehran.

Raisi sat in front of a sea of microphones, most from Iran and countries home to militias supported by Tehran. He looked nervous at the beginning but slowly loosened up over the hourlong news conference.

Asked about Iran’s ballistic missile program and its support of militias in places such as Iraq, Raisi described the issues as “non-negotiable.”

Tehran’s fleet of warplanes dates largely back to before the 1979 Islamic Revolution, forcing Iran to invest in missiles instead as a hedge against its Arab neighbors, which have purchased billions of dollars in U.S. military hardware over the years. Those missiles, with a self-imposed range limit of 1,240 miles, can reach across the Mideast and U.S. military bases in the region.

Hit by pandemic exhaustion and plummeting incomes, Iran’s healthcare professionals are emigrating in big numbers when the country can least afford it.

Iran also relies on militias such as Yemen’s Houthis and Lebanon’s Hezbollah as a counterweight to enemies such as Saudi Arabia and Israel, respectively.

On meeting Biden, Raisi answered simply: “No.” His moderate competitor in the election, Abdolnasser Hemmati, had suggested during campaigning that he’d be potentially willing to meet the U.S. president.

The White House did not immediately respond to Raisi’s statements Monday. Raisi will become the first serving Iranian president sanctioned by the U.S. government even before entering office, in part over his time as the head of Iran’s internationally criticized judiciary — one of the world’s top executioners.

Raisi, a protégé of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, has been sanctioned by the U.S. in part over his involvement in the 1988 mass executions. His victory in the balloting Friday came amid the lowest election turnout in the Islamic Republic’s history. Millions of Iranians stayed home in defiance of a vote they saw as tipped in Raisi’s favor after a panel under Khamenei disqualified his strongest rivals.

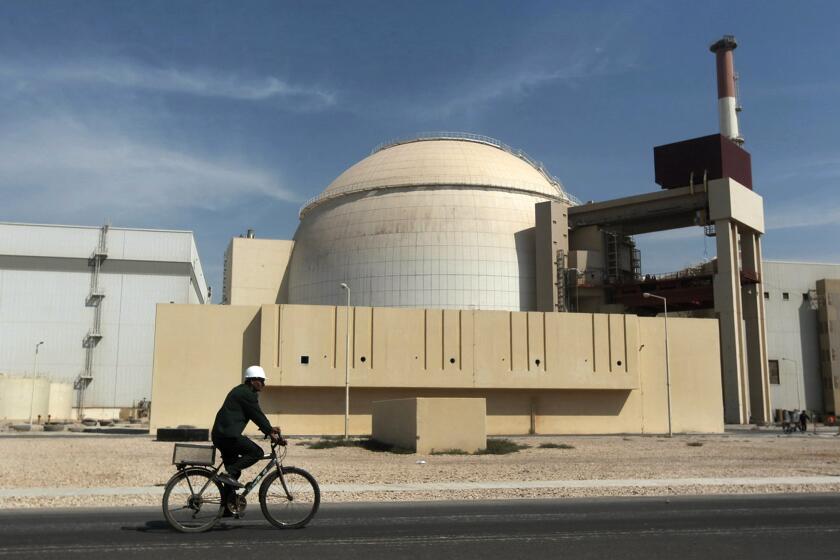

Iranian state television says the country’s only nuclear power plant has undergone a temporary emergency shutdown, but no reason was given as to why.

Of those who did vote, 3.7 million people either accidentally or intentionally voided their ballots, far beyond the number seen in previous elections and suggesting that some voters wanted none of the four candidates. In official results, Raisi won 17.9 million votes overall, nearly 62% of the total 28.9 million cast. In Tehran, the election turnout was 34%, far lower than in previous years, with polling stations noticeably empty.

Raisi’s election puts hard-liners firmly in control across the government as negotiations in Vienna continue to try to save a tattered deal meant to limit Iran’s nuclear program. Tehran is enriching uranium at 60%, its highest level ever, though still short of weapons-grade quality. Representatives of the world powers who are party to the deal returned to their capitals for consultations following the latest round of negotiations Sunday.

Top diplomats from nations involved in the talks said that further progress had been made between Iran and global powers to try to restore the landmark 2015 agreement to contain Iranian nuclear development, a deal that the Trump administration unilaterally abandoned. They said it was now up to the governments involved in the negotiations to make political decisions.

Raisi’s election victory has raised concerns that it could complicate a possible return to the nuclear agreement. In his remarks Monday, Raisi called sanctions relief as “central to our foreign policy” and exhorted the U.S. to “return and implement your commitments” in the deal.

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

On Saudi Arabia, which has recently started secret talks with Iran in Baghdad to reduce tensions with Iran, Raisi said that Iran would have “no problem” with a possible reopening of the Saudi Embassy in Tehran and that the “restoration of relations faces no barrier.” The embassy was closed in 2016 when relations deteriorated.

Raisi struck a defiant tone when asked about the 1988 executions, which saw sham retrials of political prisoners, militants and others in proceedings that would become known as “death commissions.”

After Iran’s then-Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini accepted a United Nations-brokered cease-fire between Tehran and Baghdad, members of the Iranian opposition group Mujahedeen-e-Khalq, heavily armed by Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein, stormed across the Iranian border in a surprise attack. Iran ultimately blunted its assault.

The trials began around that time, with defendants asked to identify themselves. Those who responded “mujahedeen” were sent to their deaths, while others were questioned about their willingness to “clear minefields for the army of the Islamic Republic,” according to a 1990 Amnesty International report.

The U.S. has denied a report by Iran’s state-run TV broadcaster that deals were reached for Iran to release U.S. and British prisoners for money.

International rights groups estimate that as many as 5,000 people were executed. Raisi served on the commissions.

“I am proud of being a defender of human rights and of people’s security and comfort as a prosecutor wherever I was,” he said. “All actions I carried out during my office were always in the direction of defending human rights.”

He added: “Today in the presidential post, I feel obliged to defend human rights.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.