U.S. pause on Johnson & Johnson vaccine could be felt the most in poor countries

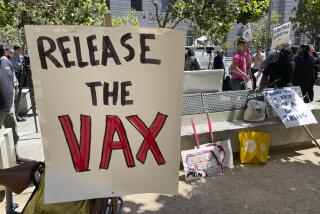

More than a billion people around the world have been waiting for the Johnson & Johnson vaccine — a cheap, easy-to-transport, one-dose injection that reduces the risk from COVID-19.

Now the global rollout has been thrown into doubt.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration, which this week recommended that use of the vaccine be paused while scientists study a possible link to extremely rare blood clots, has no authority outside the United States. But many countries follow its lead.

The fallout has begun in South Africa, where authorities also paused use of the vaccine, the only one available in the country. In February, South Africa scuttled plans to use AstraZeneca’s vaccine, which tested poorly against the coronavirus variant that is dominant there and has also been linked to blood clots.

Experts said that while the pause on Johnson & Johnson might make sense for the United States — where two other vaccines are widely available — stoppages in poorer countries with fewer options would wind up costing many more lives than they save.

“One of the dangers of this is how this is portrayed — that they somehow aren’t good enough for America but are good enough for the rest of the world,” said Dr. Jeremy Farrar, director of the Wellcome Trust, a British medical research charity. “There’s a risk of sending that signal.”

Even if the FDA ultimately clears the J&J vaccine, the pause could harm the global effort by undermining general trust in COVID-19 vaccines.

In South Africa, surveys have found that about 40% of people don’t plan to get any shot.

Why might some COVID-19 vaccines pose a small risk of blood clots while others don’t? Scientists suspect it’s related to their use of adenoviruses.

The vaccines from Johnson & Johnson and AstraZeneca — both of which use adenoviruses to help train the immune system — can be manufactured much faster and more economically than their competitors, which rely on newer mRNA technology. Because the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines require only refrigeration — not deep freezing — they’re also easier to transport and store.

“The only way to vaccinate the rest of the world in the next 12 months is through these adenovirus vaccines,” Farrar said.

Without them, the unchecked spread of disease in developing countries will increase the likelihood that new vaccine-resistant variants will emerge, he said.

Both the J&J and AstraZeneca vaccines play a major role in COVAX, a global collaboration to procure and distribute vaccines fairly across nations, particularly poorer ones. Each company has pledged to sell hundreds of millions of doses through the initiative.

The questions surrounding the AstraZeneca vaccine were already a setback to Africa, which has barely started to vaccinate its population.

The Democratic Republic of Congo received more than 1.5 million doses but has yet to use a single one due to safety concerns.

The U.S. pause on J&J — it is also on hold in the European Union while authorities there work with the FDA to evaluate the safety data — exacerbated fears that the pandemic will stretch on in Africa much longer than in other parts of the world.

China’s CanSino and Russia’s Sputnik V vaccines, which are also supplied widely to developing countries, use similar adenovirus technology, though the countries haven’t reported safety concerns. One of the adenoviruses used in Sputnik, called Ad26, is the same one used in Johnson & Johnson’s vaccine.

If the distribution of adenovirus-based vaccines is hindered, the repercussions could reverberate around the world for years to come.

“We’ll have to wait and see what the FDA finds, of course, but it would be a real shame,” said Amanda Glassman, a senior fellow and global health expert at the Center for Global Development, a nonprofit think tank in Washington.

“When you sit in parts of the U.S. and the U.K., you get the feeling that this pandemic is coming to an end,” she said. “That’s not the global picture. We cannot act like this is going away anytime soon.”

The FDA and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommended the Johnson & Johnson pause after six women, ages 18 to 48, developed a rare blood-clotting disorder within three weeks of their vaccinations. One died, and another was in critical condition this week.

Even if scientists determine the vaccine to be the cause of the blood clots, the rate of such a reaction appears to be less than 1 in a million — about half as likely as getting hit by lightning each year and far less likely than a blood clot caused by oral contraceptives.

Johnson & Johnson has played a minor role in the U.S. vaccination campaign since its vaccine was authorized in February. The vast majority of Americans who had been signed up to receive it last week were quickly switched to the two other vaccines available in the U.S.: those from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna.

U.S. regulators have not authorized use of the AstraZeneca vaccine; if they do, the vaccine stockpiled in the U.S. probably won’t be needed here.

While AstraZeneca remains the bedrock of the vaccination campaign in Britain, the EU plans to phase it out next year as the Pfizer option becomes more plentiful. Germany, Italy and Spain have limited use of the AstraZeneca vaccine to seniors.

The United States accounts for about 4% of the world’s population but almost 30% of all vaccine doses administered globally. Africa, home to 17% of humanity, accounts for 2% of all shots.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.