Former 49ers player Phillip Adams kills 5, then himself, sheriff says

Former NFL player Phillip Adams killed five people, including a prominent doctor, his wife and two grandchildren, a source says.

COLUMBIA, S.C. — Former NFL player Phillip Adams fatally shot five people including a prominent doctor, his wife and their two grandchildren before killing himself in South Carolina, authorities said Thursday.

York County Sheriff Kevin Tolson said at a news conference that investigators had not yet determined a motive in the mass shooting Wednesday in Rock Hill, S.C., just south of Charlotte, N.C.

“There’s nothing right now that makes sense to any of us,” Tolson said.

Dr. Robert Lesslie, 70, and his wife, Barbara, 69, were pronounced dead in their Rock Hill home along with grandchildren Adah Lesslie, 9, and Noah Lesslie, 5, the York County coroner’s office said.

A man who had been working at the Lesslie home, James Lewis, 38, was found shot to death outside. A sixth victim, Robert Shook, 38, was flown to a Charlotte hospital, where he was in critical condition “fighting hard for his life,” said a cousin, Heather Smith Thompson.

At Thursday’s news conference, Tolson played audio of two 911 calls, the first from an air-conditioning company that employed Lewis and Shook. One of the men, the caller said, had called him “screaming” and saying that he had been shot, and that his co-worker was shot and “unresponsive.”

“I think there’s been a bad shooting,” a different man said in a second 911 call, saying he was outside cutting his grass and heard “about 20” shots fired at the Lesslie home before seeing someone leave the house.

Tolson said evidence left at the scene of the shooting led authorities to Adams as a suspect. He said they went to Adams’ parents’ home, evacuated them and then tried to talk Adams out of the house. Eventually, they found him dead of a single gunshot wound to the head.

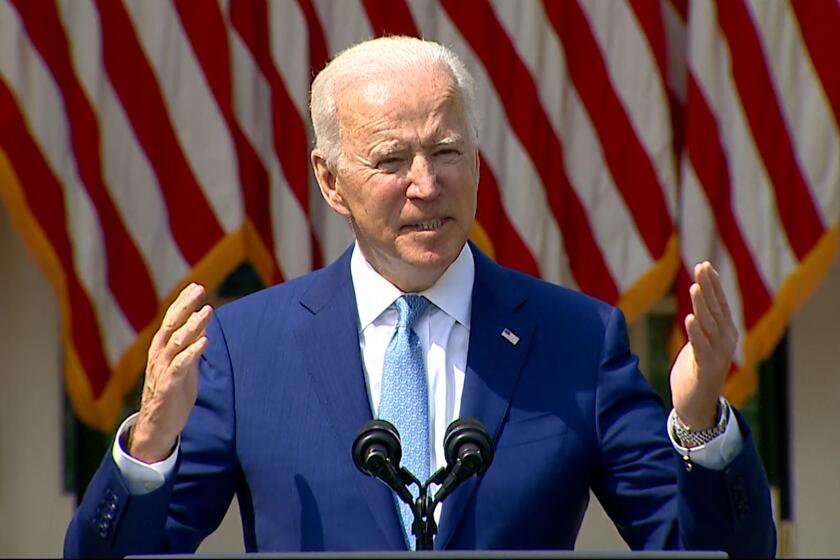

With gun limits facing opposition in Congress, President Biden will take executive actions after mass killings in his first weeks in office.

Tolson said two guns, a .45-caliber and 9-millimeter, were used in Wednesday’s shooting.

A person briefed on the investigation told the Associated Press earlier Thursday that Adams had been treated by Lesslie, who lived near his parents’ home. The person spoke on condition of anonymity because he wasn’t authorized to speak publicly.

Tolson would not confirm that Adams had been the doctor’s patient.

Lesslie worked for decades as an emergency room doctor, board-certified in emergency medicine and occupational medicine and serving as emergency department medical director for nearly 15 years at Rock Hill General Hospital, according to his website.

He and his wife had four children and nine grandchildren, and were actively involved with their church, as well as with Camp Joy, which works with children with disabilities and where Lesslie served as camp physician for a week each summer. On Thursday, Tolson said the family had asked that any memorials be made to the camp.

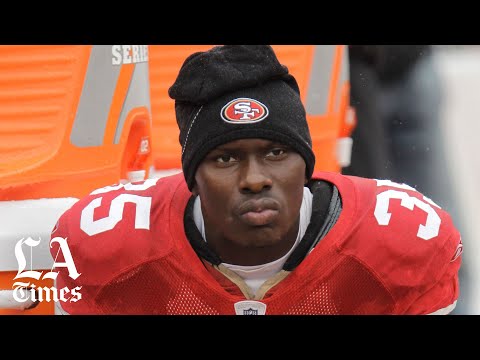

Adams, 32, played in 78 NFL games over five seasons for six teams. He joined the San Francisco 49ers in 2010 as a seventh-round draft pick out of South Carolina State. He went on to play for New England, Seattle, Oakland and the New York Jets before finishing his career with the Atlanta Falcons in 2015.

Biden’s proposals would require background checks for ‘ghost guns,’ encourage state red-flag laws and more. Yet they stop short of what advocates seek.

As a rookie, Adams suffered a severe ankle injury and never played for the 49ers again. Later, with the Oakland Raiders, he had two concussions over three games in 2012.

Whether he suffered long-lasting concussion-related injuries wasn’t immediately clear. Adams would not have been eligible for testing as part of a broad settlement between the league and its former players over such injuries, because he hadn’t retired by 2014.

Adams’ father told a Charlotte television station that he blamed football for his son’s problems.

“I can say he’s a good kid — he was a good kid, and I think the football messed him up,” Alonzo Adams told WCNC-TV.

Deputies were called around 4:45 p.m. Wednesday to the Lesslies’ home and evacuated the neighbors as they searched for a suspect.

Allison Hope, who lives across from Adams’ parents’ home, about a mile from the Lesslies, said police allowed her to return home around 9 p.m. Wednesday. Moments later, a vehicle pulled into the Adamses’ driveway and law enforcement quickly surrounded the property.

She said they spent hours negotiating with Adams, using a loudspeaker and sending in a robot to scan the house. She said authorities repeatedly asked Adams to come out, and promised to get his disabled mother out safely, before Adams shot himself.

“This is something I can’t grasp yet. I can’t put it all together and I’m trying to,” Hope said.

Adams often isolated himself, even as a player, his agent, Scott Casterline, told the Associated Press. Casterline said he spoke regularly with Adams’ father, who left him a voicemail Wednesday morning.

“This is so unlike him. He had to not be in his right mind, obviously,” Casterline said, adding that Adams struggled away from the game.

“He had an injury his rookie year. Some teams wrote him off and he had that stigma of a guy who was hurt,” Casterline said. “It was hard for him to walk away from the game, especially a guy as dedicated as he was.

“We encouraged him to explore all of his disability options, and he wouldn’t do it,” Casterline added. “I knew he was hurting and missing football, but he wouldn’t take health tips offered to him. He said he would but he wouldn’t.

“I felt he was lost without football, somewhat depressed.”

Breaking News

Get breaking news, investigations, analysis and more signature journalism from the Los Angeles Times in your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Cowboys cornerback Kevin Smith, who trained with Adams before the 2010 draft, said he had opened a shop selling smoothies before the COVID-19 pandemic. Both he and Casterline emphasized Adams didn’t drink or do drugs.

Lesslie founded two urgent-care centers and had traveled the country giving lectures to an emergency nurses’ group, his website said. He wrote a weekly medical column for the Charlotte Observer and became a prolific author, writing several volumes with advice on how to lower cholesterol or blood pressure and lose weight.

The physician also wrote a number of collections of what he termed “inspiring true stories” from his work.

“I know without a doubt that life is fragile,” Lesslie wrote in one of those books, “Angels in the ER.”

“I am convinced we need to take the time to say the things we deeply feel to the people we deeply care about.”

A statement from the Lesslie family said they were “in the midst of the unimaginable” but felt assured by faith that their “hearts are bent toward forgiveness and peace.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.