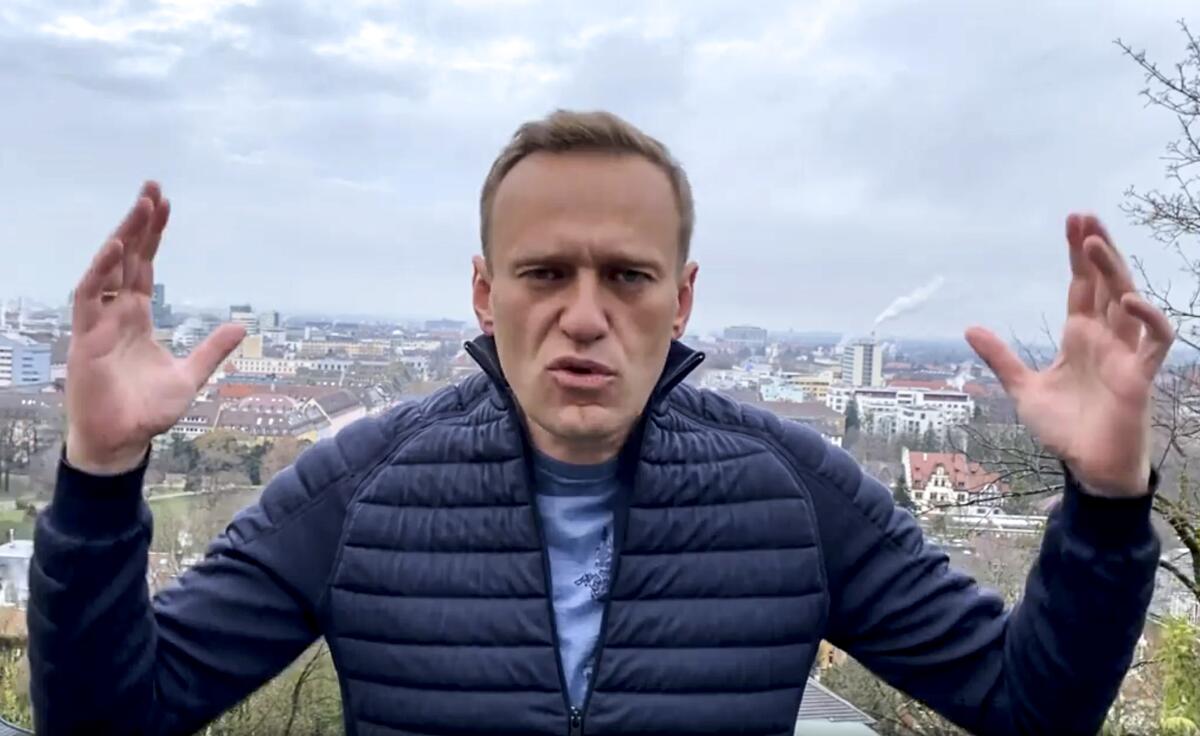

How dissident Alexei Navalny’s new standoff with Russia’s Putin could play out

The long-running confrontation between the Kremlin and Alexei Navalny took a darker turn this week as Russia’s best-known opposition figure launched a hunger strike to demand proper medical attention and protest his prison treatment.

Now his allies are openly voicing fears that Russian President Vladimir Putin once again wants him dead.

Navalny, 44, barely survived a poisoning seven months ago with a military-grade nerve agent, an attack Western governments blamed on the Russian security services. Now he is serving a 2½-year sentence in a harsh penal colony east of Moscow, after returning to Russia in January from Germany, where he spent months convalescing from his poisoning ordeal.

The Kremlin denied any responsibility for Navalny’s poisoning, but his case has worsened Moscow’s already tense relations with the United States and the 27-nation European Union. It also triggered one of the broadest and most sustained outpourings of domestic anger yet against Putin, who has been in power for more than two decades.

But analysts say that despite a groundswell of street protests this year to demand Navalny’s freedom — with more such mass demonstrations potentially in the works — neither the West nor his supporters at home have much real leverage against the state machinery presided over by Putin.

Even so, Navalny appears to have gotten under the Russian leader’s skin in a way that few opponents have managed to do, daring to mock Putin personally and highlighting the issue of official corruption, a key driver of discontent. Support for Navalny also taps a youthful demographic that could be a harbinger of longer-term gains for his political movement.

Here is some background about Navalny and where the latest confrontation might lead.

How serious is the danger to Navalny?

By all appearances, it is considerable. Supporters were alarmed when he was sent to a maximum-security facility known as Pokrov IK-2, about 60 miles east of Moscow, which is notorious for harsh conditions. This week, his Instagram account said he had been denied painkillers or access to a doctor to treat debilitating back and leg pain. He also told of sleep deprivation due to guards shining a light on his face every hour, ostensibly to ensure he had not escaped.

On Wednesday, the account maintained in his name by aides posted a handwritten letter from Navalny announcing the start of his hunger strike, in which he asked: “What else could I do?” A series of Twitter posts on Thursday said he had lost 18 pounds even before his hunger strike commenced.

Russian democracy activist Vladimir Kara-Murza, speaking at an online panel Wednesday organized by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, cited a “grave, dangerous and deteriorating” situation for Navalny. American-born British businessman Bill Browder, who has championed legislation on sanctions against Russia, likened Navalny’s case to that of lawyer Sergei Magnitsky, who died in Russian prison in 2009. “Putin is trying to kill him in slow motion,” Browder wrote on Twitter this week.

The Kremlin has declined to comment on Navalny’s condition, and prison authorities say his treatment has been in accordance with the law.

How is Putin playing this?

Analysts say the Russian leader runs a degree of political risk by allowing Navalny’s condition to deteriorate to the point that his life is endangered. If Navalny were to die in custody, “there’s a danger of him becoming a martyr and delivering a boost to his supporters as well,” said Elina Treyger, a political scientist with the Rand Corp.

In launching his hunger strike, Navalny “just upped the ante,” she said. Anticipating the dangers he faced in custody, the activist previously told supporters that if anything happened to him while he was imprisoned, no one should believe any official claim that he killed himself.

U.S. and European governments have repeatedly called for Navalny’s release, citing his previous conviction on fraud charges, and the parole violation for which he is currently imprisoned, as politically motivated. German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Emmanuel Macron raised fresh concerns over Navalny’s health and rights in a video call with Putin this week. But a Kremlin readout on the call said Putin responded with an “objective explanation” of Navalny’s situation, suggesting he rebuffed their appeals.

Western pressure can sometimes backfire, analysts say, because Putin is so skilled at using Navalny’s plight to portray himself as a bulwark against outside meddling in Russian affairs. State media routinely describe Navalny as a foreign agent and his supporters as dupes of the West, a message that often plays well with the Russian public.

To outside eyes, the official Russian media offensive against Navalny can seem crude and heavy-handed, especially compared with the skilled use of online outlets by the jailed activist and his team.

Postings in his name frequently employ sly humor and feature investigative blockbusters such as the “Putin’s Palace” video this year — detailing an opulent Black Sea compound purportedly paid for by the president’s cronies — which has garnered more than 115 million views on YouTube.

On Thursday, in what appeared to be classic trolling by the Kremlin, former Russian agent Maria Butina, who became a cause celebre at home when she served jail time in the United States, was dispatched to Navalny’s penal colony by the pro-government channel RT to report on his case.

Navalny’s Twitter account, describing her as a “wretched propagandist,” said Butina was “shouting that this is the best and most comfortable prison.”

What comes next?

Navalny’s associates have said he may revive street protests that were called off this year after authorities responded with tens of thousands of arrests. To gauge support, his team has set up on online tool, with a goal of half a million backers expressing willingness to take part. By Thursday, about 370,000 people had signed up.

But surveys suggest there is probably a numerical ceiling on such backing, in part because even many Russians who dislike Putin see him as a source of stability. Opinion polls about Navalny “are very mixed,” said Kadri Liik, a senior policy fellow and Russia expert at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“Some people support him, some are indifferent, and some believe he might be a Western agent,” she said.

In the meantime, Russian authorities have a variety of potent means to exert pressure not only on Navalny but also on his associates and supporters.

Many members of Navalny’s team live in exile, but Putin’s government has shown willingness to use a familiar Soviet-era tactic of retaliation against family members. The father of Ivan Zhdanov, the director of Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation, was detained over the weekend, a move Zhdanov said was aimed at him.

Special correspondent Vasiliy Kolotilov in Moscow contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.