What’s ahead as Trump impeachment trial begins

WASHINGTON — Former President Trump’s historic second impeachment trial will force the Senate to decide whether to convict him of incitement of insurrection after a violent mob of his supporters lay siege to the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 6.

Although Trump’s acquittal is expected, Democrats hope to gain at least some Senate Republican votes by linking Trump’s actions to a vivid description of the violence, which resulted in five deaths and sent lawmakers fleeing for safety. The House impeached Trump on Jan. 13, one week later.

Trump’s lawyers say the trial should not be held at all because the former president is now a private citizen. They argue that he did not incite the violence when he told his supporters to “fight like hell” to overturn his defeat.

A look at the basics of the impeachment trial:

How does the trial work?

As laid out by the Constitution, the House votes to impeach and the Senate then holds a trial on the charge or charges. Two-thirds of senators present can convict.

The House appointed nine impeachment managers, who will present the case against Trump on the Senate floor. Trump’s defense team will have equal time to argue against conviction.

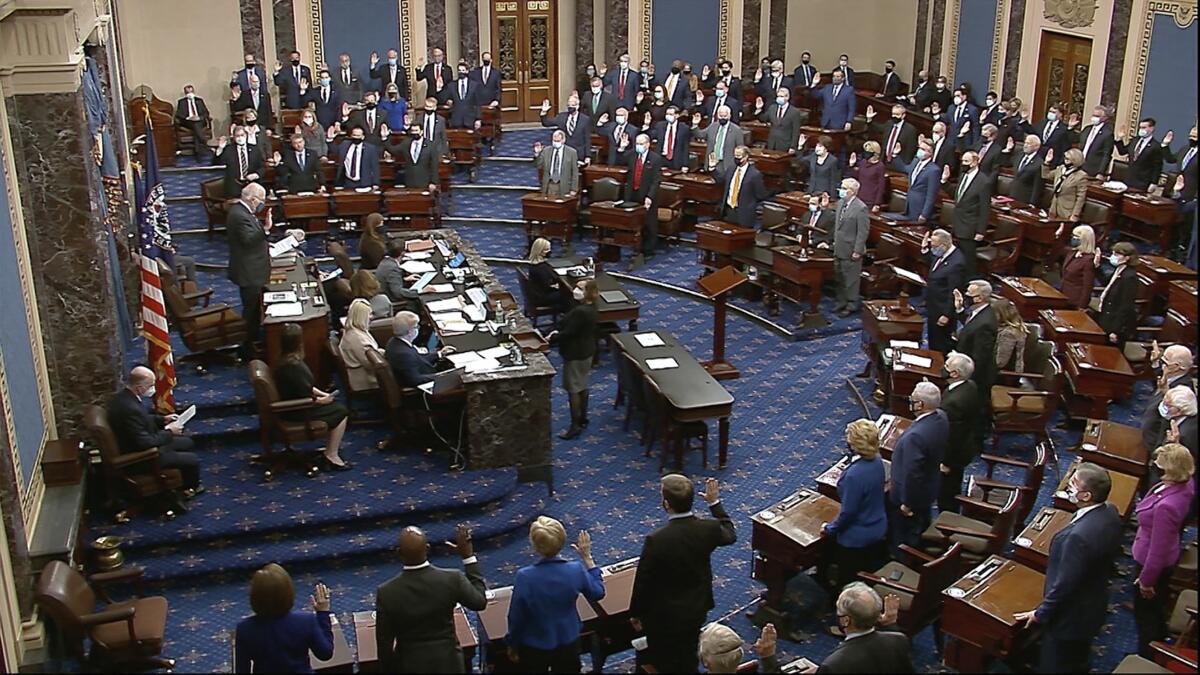

The chief justice of the United States normally presides over the trial of a president, but because Trump has left office, the presiding officer will be Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), who is the ceremonial head of the Senate as the longest-serving member of the majority party.

Once the senators reach a final vote on the impeachment charge — this time there is just one, incitement of insurrection — each lawmaker will stand up and cast their vote: guilty or not guilty.

How long will the trial last?

Likely more than a week. The agreement between Senate leaders provides for up to 16 hours for both prosecutors and the defense to make their arguments, starting Wednesday, with no more than eight hours of arguments per day. Later, there will be time for senators to ask questions, and there could be additional procedural votes.

Under the agreement, the trial will open Tuesday with four hours of debate on whether the trial is constitutional. The Senate will then vote on whether to dismiss the charge against Trump. If that vote fails, as expected, the House managers will begin their arguments Wednesday and continue into Thursday.

Trump’s lawyers are likely to begin their arguments Friday and finish Saturday. That almost certainly means a final vote on Trump’s conviction won’t happen until next week.

Trump’s first impeachment trial, in which he was acquitted on charges that he abused power by pressuring Ukraine to investigate now-President Joe Biden, lasted almost three weeks. But this one is expected to be shorter, as the case is less complicated and the senators know many of the details already, having been in the Capitol during the insurrection.

And although the Democrats want to ensure they have enough time to make their case, they do not want to tie up the Senate for long. The Senate cannot confirm Biden’s Cabinet nominees and move forward with their legislative priorities, such as COVID-19 relief, until the trial is complete.

Will there be witnesses?

It appears unlikely, for now, though that could change as the trial proceeds. Trump himself has declined a request from the impeachment managers to testify.

Although Democrats argued vociferously for witnesses in the last impeachment trial, they were not allowed to call them after the GOP-controlled Senate voted against doing so. This time, Democrats feel they don’t need witnesses because they can rely on the graphic images of the insurrection that played out on live television. They also argue that the senators were witnesses themselves.

If the managers do decide they want to call witnesses, the bipartisan agreement for the trial allows them to ask for a vote. The Senate would have to approve subpoenaing any witnesses for the trial.

Why try Trump when he is out of office?

Republicans and Trump’s lawyers argue that the trial is unnecessary, and even unconstitutional, because Trump is no longer president and cannot be removed from office. Democrats disagree, pointing to opinions of many legal scholars and the impeachment of a former secretary of war, William Belknap, who resigned in 1876 just hours before he was impeached over a kickback scheme.

Although Belknap was eventually acquitted, the Senate held a full trial. And this time, the House impeached Trump while he was still president, seven days before Biden’s inauguration.

If Trump were convicted, the Senate would take a second vote to bar him from holding office again, Schumer said Monday. Democrats feel that would be an appropriate punishment.

In response to GOP efforts to dismiss the trial, Democrats argue that there should not be a “January exception” for presidents who commit impeachable offenses just before they leave office. They say the trial is necessary not only to hold Trump properly accountable but also so they can deal with what happened and move forward.

“You cannot go forward until you have justice,” said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi last week. “If we were not to follow up with this, we might as well remove any penalty from the Constitution of impeachment.”

How is this trial different from Trump’s first trial?

Trump’s first trial was based on evidence uncovered over several months by the House about a private phone call between Trump and the president of Ukraine, as well as closed-door meetings that happened before and afterward. Democrats held a lengthy investigation and then compiled a report of their findings.

In contrast, the second trial will be based almost entirely on the visceral experience of a riot that targeted the senators themselves, in the Capitol building. The insurrectionists even breached the Senate chamber, where the trial will be held.

The fresh memories of Jan. 6 could make it easier for the House impeachment managers to make their case, but it doesn’t mean the outcome will be any different. Trump was acquitted in his first trial a year ago Friday with only one Republican, Utah Sen. Mitt Romney, voting to convict, and there may not be many more guilty votes this time around.

In a test vote Jan. 26, only five Senate Republicans voted against an effort to dismiss the trial — an early indication that Trump is likely to be acquitted again.

What will Trump’s lawyers argue?

In a brief filed Monday, they argued that the trial was unconstitutional, that Trump did nothing wrong and that he did not incite the insurrection during his Jan. 6 speech to supporters.

While the House impeachment managers say Trump is “singularly” responsible for the attack on the Capitol, Trump’s lawyers say the rioters acted on their own accord. They suggest that Trump was simply exercising his 1st Amendment rights when he falsely disputed the election results and told his supporters to fight — a term they note is often used in political speeches.

The brief goes after the impeachment managers personally, charging that the Democrats have “Trump derangement syndrome,” are “selfish” and are only trying to impeach Trump for political gain.

There was no widespread fraud in the election, as Trump claimed falsely over several months and again to his supporters just before the insurrection. Election officials across the country, and even former Atty. Gen. William Barr, contradicted his claims, and dozens of legal challenges to the election put forth by Trump and his allies were dismissed.

What would acquittal mean for Trump?

A second impeachment acquittal by the Senate would be a victory for Trump — and would prove he retains considerable sway over his party, despite his efforts to subvert democracy and widespread condemnation from his GOP colleagues after Jan. 6.

Still, acquittal may not be the end of attempts to hold him accountable. Sens. Tim Kaine (D-Va.) and Susan Collins (R-Maine) floated a censure resolution after last month’s vote made clear that Trump was unlikely to be convicted.

Although they haven’t said yet if they will push for a censure vote after the impeachment trial, Kaine said last week that “the idea is out there on the table and it may become a useful idea down the road.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.