Illinois replaces its House speaker, the longest-serving legislative leader in U.S.

- Share via

SPRINGFIELD, Ill. — The Illinois House on Wednesday elected its first Black speaker to replace the longest-serving legislative leader in modern U.S. history, picking Democratic Rep. Emanuel “Chris” Welch for the job and pushing aside Michael Madigan after he was implicated in an ongoing bribery investigation.

Welch, an eight-year House veteran from the Chicago suburb of Hillside, garnered 70 votes from the 118-member House days after emerging as the front-runner alternative to Madigan, 78, who was first inaugurated as a House member half a century ago.

Madigan has wielded the gavel for 36 of the last 38 years and had sought another term in his post despite 19 members of his caucus announcing their opposition in the last six months. After coming up short in a Sunday caucus vote, Madigan suspended his campaign, allowing lawmakers to consider others rather than force a potentially drawn-out floor fight that would paralyze all other business.

“It is time for new leadership in the House,” Madigan said in a statement. “I wish all the best for Speaker-elect Welch as he begins a historic speakership. It is my sincere hope today that the caucus I leave to him and to all who will serve alongside him is stronger than when I began.”

Last summer, Madigan was identified in a Justice Department investigation as the beneficiary of a years-long bribery venture involving utility giant Commonwealth Edison. It has thus far yielded a $200-million fine on the utility giant, a ComEd executive’s guilty plea and indictments of four others, including Madigan’s closest confidante. Madigan has not been charged with a crime and has denied wrongdoing.

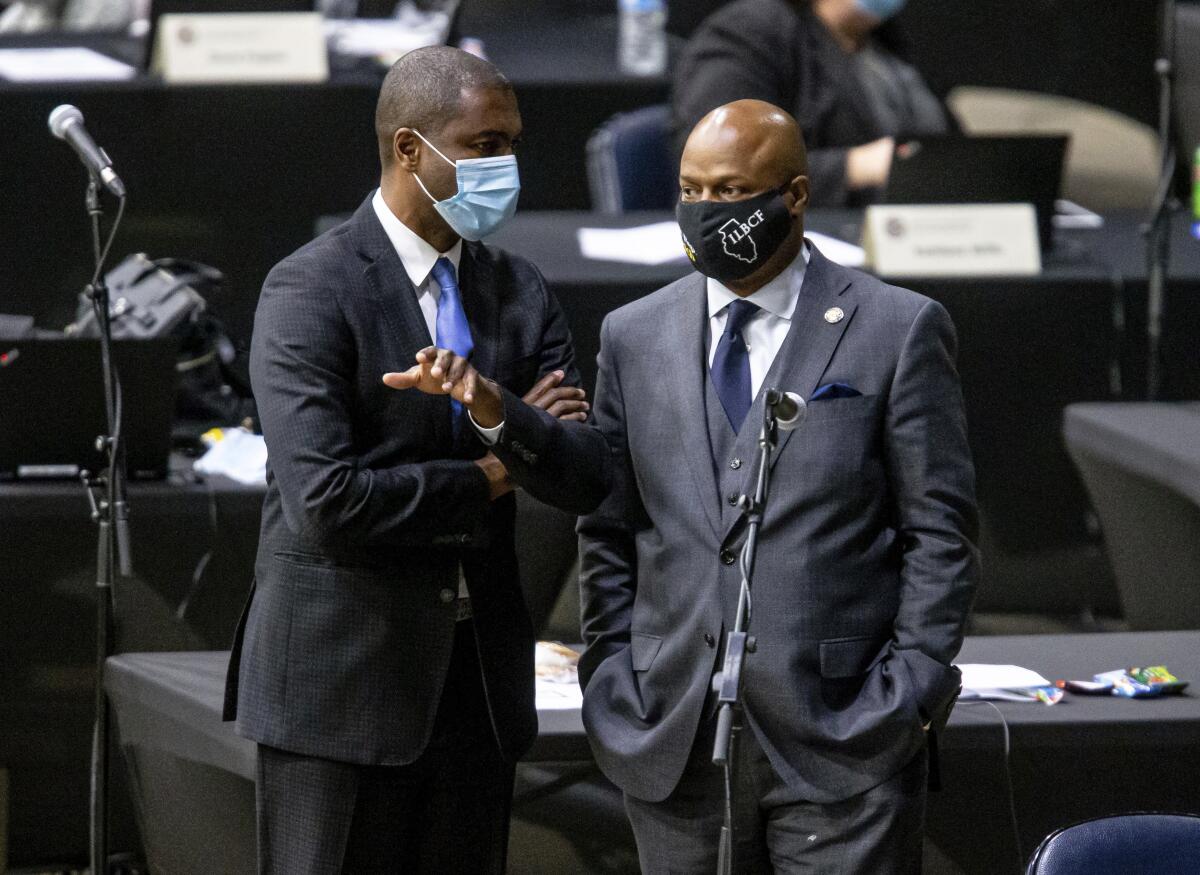

Illinois’ considerable challenges await Welch. COVID-19 has claimed more than 17,800 lives in the state and forced a House retreat to the downtown Springfield convention center, where lawmakers with face coverings could spread out to avoid transmission. There’s also a $4-billion hole in the current state budget, largely driven by tax revenue lost to the pandemic, on top of billions of dollars of existing indebtedness.

The first Black leader of the House follows two Black Senate presidents: Cecil Partee from 1975 to 1977 and Emil Jones Jr., who molded the political career of a young Barack Obama, from 2003 to 2009.

Welch has been part of Madigan’s inner circle, serving as chairman of the powerful Executive Committee. He was chosen last fall to be chairman of an investigative committee demanded by Republicans to review Madigan’s involvement in the ComEd scandal. Welch abruptly brought the probe to a close, claiming that the Republicans had staged a “sham show trial.”

That incensed House Minority Leader Jim Durkin, who had prompted the committee review by filing a charge of conduct unbecoming a legislator. On Tuesday, with Welch’s prospects rising, Durkin derided him as a continuation of “the model of Madigan Inc.”

In his first comments as speaker, Welch tried to bridge the decades-long partisan divide.

“Today will be the last time I talk about us as Democrats or Republicans, because I want to talk about us being united,” he said. “We’re going to work together to move this state forward.”

Durkin, who was elected to his fifth term as minority leader, welcomed Welch’s comments but urged Welch to keep his promise of independence and “avoid taking hand signals and homing pigeons from the 13th Ward,” a reference to Madigan’s southwest-side Chicago home. Welch rolled his eyes and shook his head.

Madigan’s leadership has been questioned in recent years, even before the ComEd allegations surfaced. The scrutiny included his handling of sexual harassment allegations and a scathing report he commissioned that detailed the environment of bullying and intimidation in the speaker’s office under his chief of staff of 25 years.

Welch’s connection to Madigan is especially disturbing to opponents on the issue of gender relations. The Chicago Tribune reported Tuesday that Hillside police were summoned in 2002 when a woman claimed Welch repeatedly slammed her head into a kitchen countertop. She declined to press charges, and Welch denied the claim. When he was a school board president, Welch faced a 2010 federal lawsuit filed by a dean who claimed she lost her job in retaliation for ending a relationship with Welch. Settlement talks had begun when a motion was filed to dismiss the case.

It is unclear whether Madigan, who took his first House oath in 1971, will remain in the Legislature. He took over as speaker just as a constitutional amendment reduced the size of the House, creating single-member representative districts and consolidating power at the top. Madigan took advantage of that, setting the agenda, deciding what legislation would be debated and, after 1998, when he took over as chairman of the Democratic Party, deciding whom the party would support for office.

Madigan was long considered among the state’s most powerful politicians, right alongside Chicago’s mayor, six of whom have occupied City Hall during Madigan’s reign.

Former Republican Gov. Bruce Rauner, who tried to bring Madigan down, famously claimed that it was Madigan, not he, who was in charge of the state. The Rauner-Madigan rivalry led to a two-year stalemate over a state budget, driving the state’s debt deeper, before Madigan persuaded some Republicans to add needed votes for an income tax hike to settle the matter. It was Madigan’s intractability during that stretch that his allies used to bolster his standing in recent weeks while lobbying for his reelection.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.