HOUSTON — Doctors did everything they could to keep Terry Hill off a ventilator.

They’d treated 140 COVID-19 patients since the pandemic began, almost all successfully, in part by not resorting to ventilators. But as the virus attacked the 65-year-old’s lungs, a medical team in hazmat suits arrived in one of United Memorial Medical Center’s new intensive care isolation wings to insert a breathing tube.

“We have no option,” Dr. Joseph Varon, a pulmonologist, said from behind two masks and a face shield.

Hill nodded, too short of breath to talk. His chest heaved. His heart monitor beeped a steady pulse. Nurses and medical students rushed in and out. On the television above his bed, Hill could see a Texas tavern owner who had sued to stop the governor from closing bars ahead of the Fourth of July: “You are not going to put me out of business!”

The medical team pressed closer. Hill caught sight of a plastic hook the size of his hand and a tube as long as his arm. He began to tremble.

Varon called for sedatives. He reached out to steady Hill’s arm.

“You can do this,” he said.

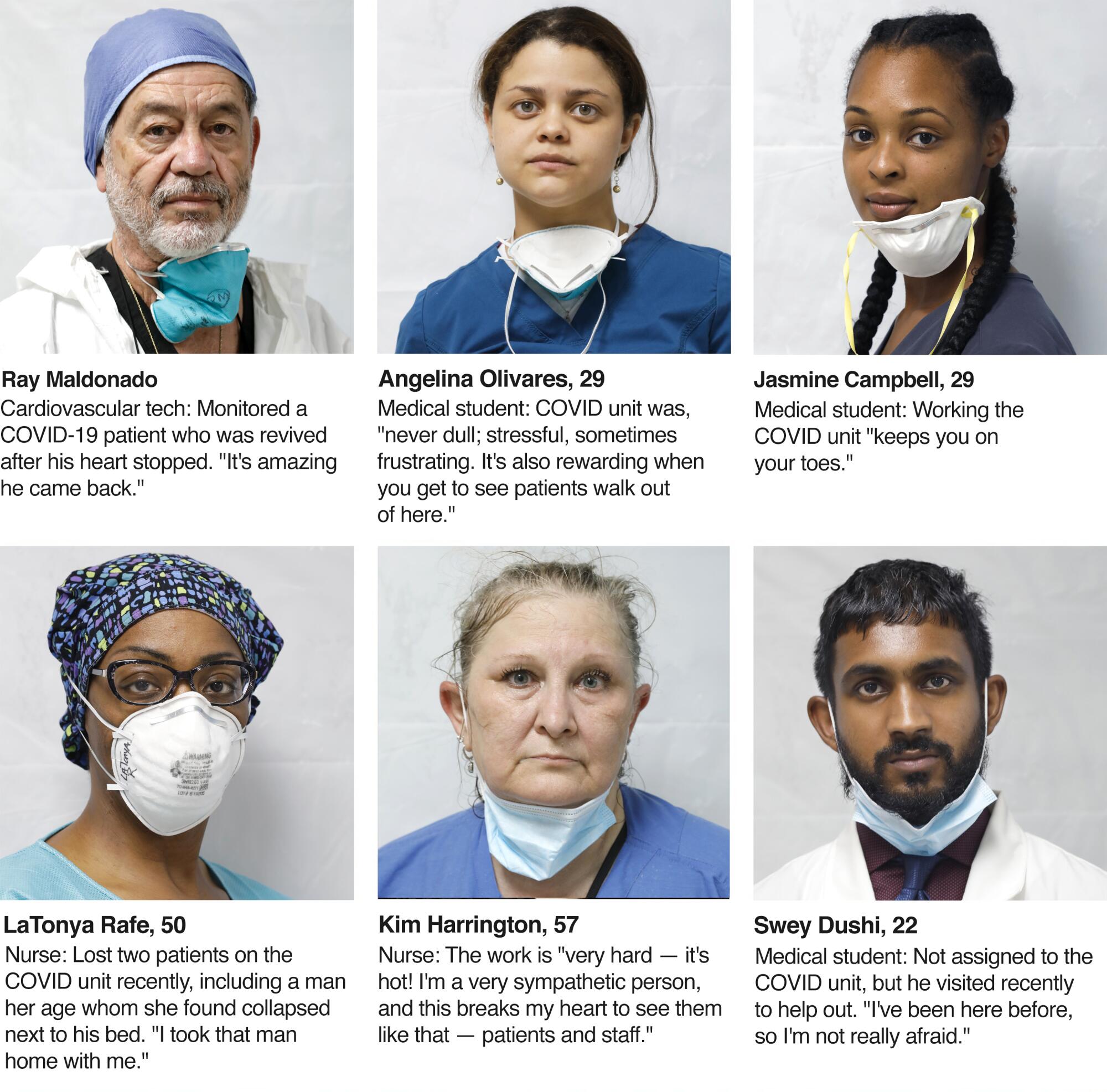

No one could be sure. During the last month, Varon and his staff had lost their first five patients, including a 34-year-old hotel worker. They had also admitted their first colleagues, a nurse and a medical student. A handful of patients were now on ventilators, including a local nightclub owner who fell ill after reopening last month.

The virus had Texas spiraling in a free-fall no one could stop. On Friday, Texas reported 7,555 new COVID-19 cases and 7,652 hospitalizations — a record for the fifth consecutive day. The state has now seen a total of 183,532 cases and 2,575 deaths.

Gov. Greg Abbott, a Republican, had for weeks resisted pleas from Houston’s mayor and other officials to issue mandatory mask and stay-at-home orders, despite a spike in infections in the state’s largest cities. He relented with a mask order for hard-hit areas beginning Friday. Houston’s Texas Medical Center — the largest hospital complex in the world — was filling with COVID patients. A Houston arena was preparing to temporarily house overflow. The hospital where Hill was being treated was 80% full.

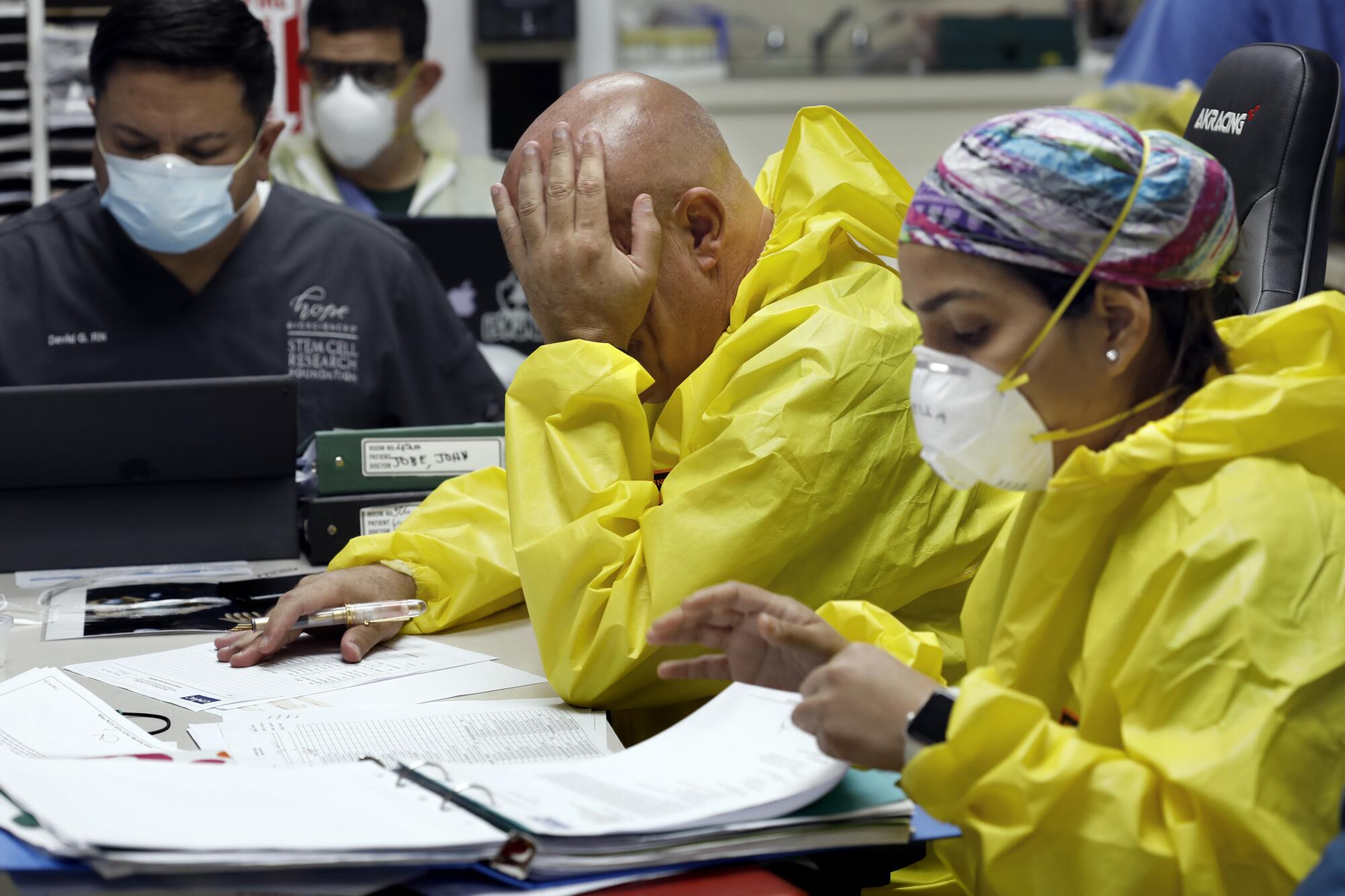

Hill, a truck driver, was another life crisis, another troubling statistic, in a snapshot of America. He was soon sedated, unconscious, eyes staring blankly. Varon and his team inserted the tube into Hill’s mouth. The ventilator took over; he stopped breathing on his own. The heart monitor flashed. Something was wrong.

Hill’s pulse grew thready. He was dying.

“Start compressions,” Varon commanded.

Two medical students began pumping Hill’s chest. A dozen students and nurses rushed in with surgical tools and echocardiography equipment to check Hill’s heart.

“Faster, people!” Varon shouted.

A technician stroked the echocardiogram wand across Hill’s body, projecting a black-and-white image of his chest on the screen. It was riddled with blood clots, including a massive one in his heart, which had just stopped beating.

Houston-based Dr. Joseph Varon and his team work to save COVID-19 patient Terry Hill, whose heart stopped while being put on a ventilator. Hill gave the Los Angeles Times permission to tell his story.

“It’s a dying heart,” Varon said.

He shouted: “Continue compressions! Come on, get on top of the bed!”

Students climbed onto the gurney, pumping furiously. Others fetched epinephrine and blood-thinning medication they hoped would stabilize their patient. Meanwhile, Varon and his team inserted an arterial line into Hill’s groin to better monitor his blood pressure.

The technician pulled up the image of Hill’s chest on his monitor again. Varon examined it.

“We have a beating heart,” he said.

In a hospital room in a nation of rising deaths, Hill had been saved. It had taken doctors and nurses half an hour to revive him. It wasn’t clear how long he had been deprived of oxygen, or what damage that had wrought on his brain. The team brought ice to cool Hill’s body, hoping to minimize the effects.

The onslaught of severe COVID-19 cases has worsened at United Memorial since the first ones arrived 106 days ago. Some patients suffer psychologically; others, like Hill, crash.

“This is what we’ve been going through every day,” Varon said, his gloves and hazmat suit bloody. “People don’t believe what’s going on: We’re bringing people back from the brink of death.”

During the past month, Varon’s 117-bed hospital quadrupled its COVID-19 unit from 20 to 80 beds. The hospital lab went from handling 40 tests a day to hundreds. The COVID-19 outpatient clinic and drive-through testing also expanded, from one site testing 300 people a day to eight sites testing 2,000. The percentage of people testing positive climbed to almost 17%, well above the state’s rate (14%) and more than twice the nation’s (7%). About half of those who tested positive at the hospital had no symptoms.

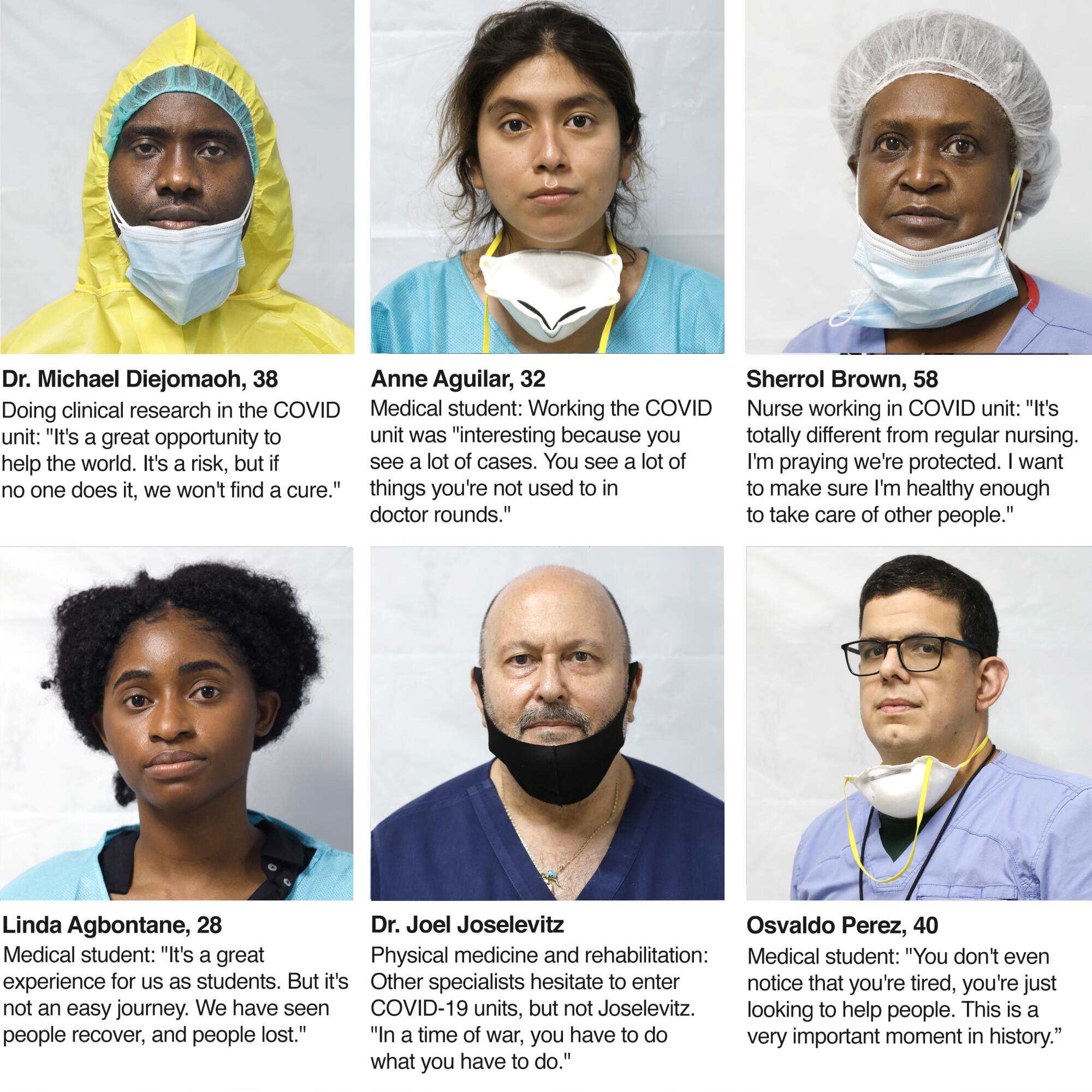

Most of Varon’s staff are people of color, some with relatives who have died of COVID. All of them know someone who has tested positive. Unlike the upscale Texas Medical Center to the south, where Varon has an additional 72 overflow beds prepped, United Memorial is on the city’s low-income north side. Among the hospital’s COVID patients, 60% have no insurance.

Varon has treated a 19-year-old man with few symptoms but a deadly blood clot in his lungs, a 29-year-old woman who was turned away from another private hospital and a woman who fell ill after hosting a 150-seat family funeral for her husband — who had died of COVID-19. Some of those the hospital called to notify about positive tests had been at parties, or worked at nursing homes and didn’t want to stop.

Last week the unit was so full, they had to have a patient wait in the parking lot.

“The problem is if we get all the patients at the same time,” Varon said. “That’s the situation we’re in.”

He and his colleague Dr. Joseph Gathe Jr. have tried to innovate COVID-19 treatment, adjusting a cocktail of medications that includes steroids, blood thinners, vitamin C and the controversial malaria drug hydroxychloroquine.

Some of their patients are participating in FDA-approved randomized blind drug trials involving stem cells and DAS181, a retroviral drug produced by San Diego-based Ansun BioPharma. The team, which plans to soon join a third trial of Regeneron antibody treatment, has also installed a proning machine, which rotates patients to increase their lung capacity — “like a rotisserie,” Varon said.

It’s not clear yet whether the stem cells and other new treatments work. The machine helped one patient, but another died. The medical student and nurse who tried to resuscitate him were admitted to the COVID unit soon after.

Nurse Tanna Ingraham initially tested negative for COVID-19 last week. Then doctors ordered a chest scan. Ingraham, 43, knew as soon as she saw the gauzy image of her lungs: “I had COVID everywhere.”

The beach vacation she had planned has instead become days of isolation. She sent her 9- and 10-year-old daughters to stay with their father in Los Angeles. She was receiving the stem cell treatment but worried about blood clots, her barking cough and recent panic attacks. COVID had left her dependent on the very team she had left short-staffed.

“This virus is taking everything that I have,” she said.

The virus exacts a psychological toll, Varon said. He’s had patients run naked from their rooms, pull out IVs and oxygen lines, search the floor for an imaginary lost cellphone, insist a fellow patient was their son and call 911 to rescue them.

Nurse LaTonya Rafe, 50, watched on a monitor as a patient her age whom she had just strapped into restraints wiggled free, yanked out his IV and collapsed. She rushed to pull on protective gowns and gloves before entering the unit.

“When we got in there, he was on the ground. We turned him over, and he had that zombie look,” she said. He soon died, as did another of her patients.

“Something’s changing,” she said.

Varon’s not sure whether the delusions are a function of the virus, which could be mutating or impacting brain function by elevating patients’ ammonia levels. It may just be the stress of isolation or dire news reports. He’s considering blocking patients’ access to news in their rooms.

During rounds this week, Varon visited one of his most troubled patients.

Ricardo Trevino, 49, had waited more than a week to get tested and admitted to the hospital. He worried his lungs had suffered irreparable damage. He was participating in one of the new drug trials but had lost hope.

“Every day he’s doing his will, saying he’s going to die. When a patient tells you that, they usually do,” Varon said before entering Trevino’s room.

“You are not going to die. Not on my watch,” Varon told him.

“But the damage is extensive,” said Trevino from where he lay in his bed, exhausted and feverish, draped in a towel.

Varon explained that Trevino’s lungs were inflamed, not scarred. He also reminded the patient that many of the virus’ long-term effects are still unknown.

Trevino, who works in communications, could barely breathe. He felt air seep through his lungs like a sponge filled with wet concrete. He worried the virus was eating away at his liver. He couldn’t sit up, let alone walk. He blamed himself for not realizing how dangerous the virus was and kept thinking, “If I had just come earlier …”

“You are going to get better,” Varon said, “but I need your help.”

Trevino nodded, and the doctor moved on. The Fourth of July weekend was coming. He needed to heal and discharge patients, before he ran out of beds.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.