‘We don’t have law and order’: Black and Latino business owners face destruction in Minneapolis

- Share via

MINNEAPOLIS — Abdishakur Elmi looked on in horror as flames raged and smoke billowed from the roof of the brick building next to his restaurant.

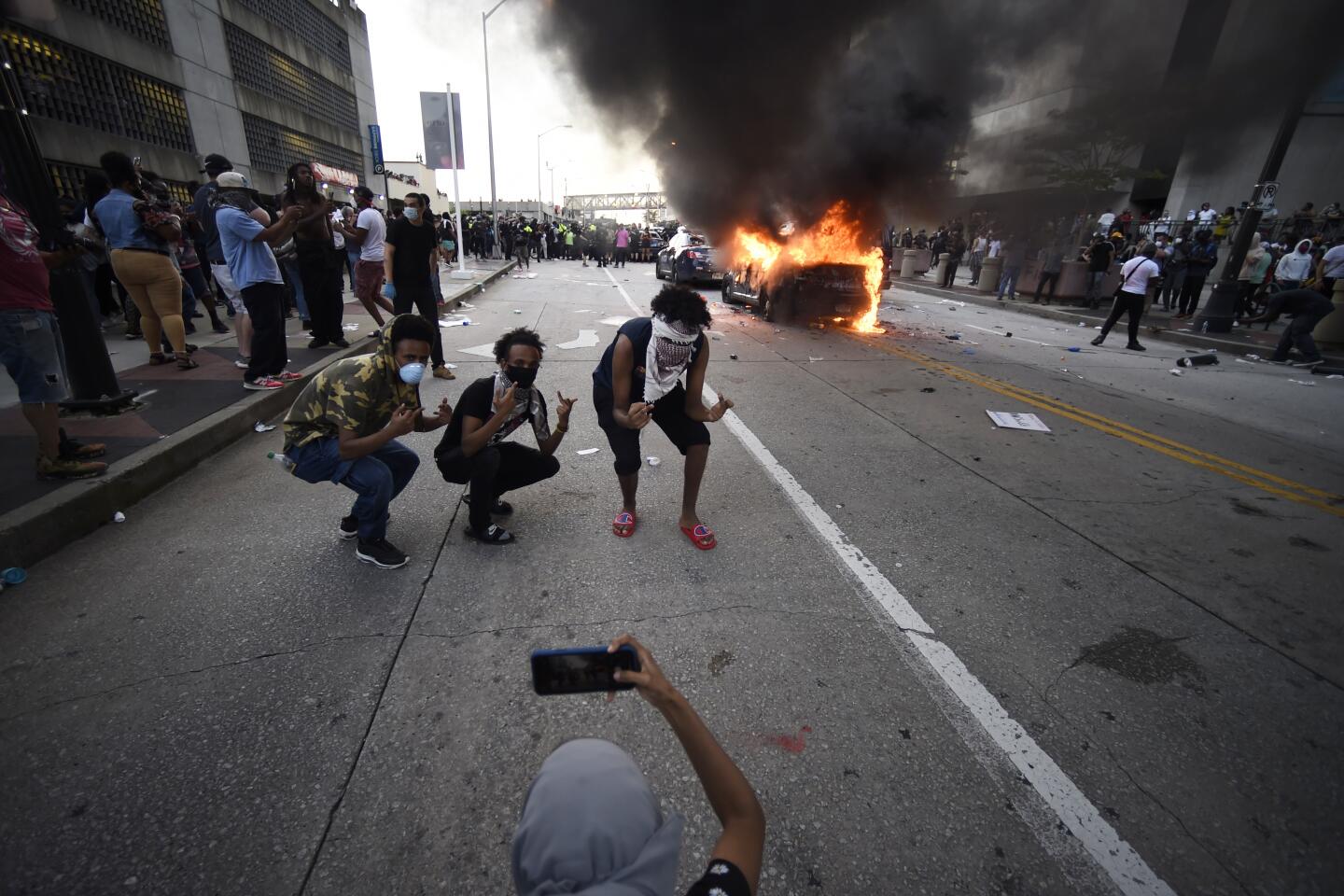

A single truck and a few firefighters battled the blaze that had already consumed several neighboring businesses overnight in a gentrified section of East Lake Street, a major thoroughfare. The police station had been set alight down the street, and protesters who had overrun it milled with the curious in smoky morning light.

The neighborhood was under siege. The blaze threatened Hamdi Restaurant, which Elmi founded after emigrating in 1996 from Somalia to the Twin Cities, a landmark for what would become the largest Somali American community in the country. The governor had deployed the National Guard overnight, but no troops had appeared at the restaurant.

“I don’t see the government. I don’t see the power,” said Elmi, 55, as he sat in his car trying to avoid the acrid air.

East Lake Street on the city’s south side has become a haven for minority-owned businesses, particularly African and Latino immigrant entrepreneurs who managed to thrive in this progressive Midwest city. Across the street from Elmi’s restaurant, the first floor of the historic Midtown Exchange, built in 1928, was transformed over the past decade into Midtown Global Market, a modern bazaar featuring an organic produce market and craft brewery alongside African art and Scandinavian pastries — a nod to the area’s early settlers.

The street echoed with accents. But no one could make sense of it — how life had suddenly changed in an ill-fated instant. Everyone knew, but it was hard to put into words. Elmi said he and many of his neighbors were disturbed by the video of a police officer kneeling on George Floyd’s neck before he died. Elmi couldn’t even finish watching it.

That video, which like so many before it went viral, sent a shiver down East Lake Street. Demonstrators marched and swarmed; the mayor and police chief pleaded for calm. President Trump tweeted, suggesting protesters could be shot. But the rage widened, and some shopkeepers — watching the looters gather — retreated in despair as police vanished from the 3rd Precinct and chaos took hold.

Hafsa Islam, the daughter of the owner of the nearby Gandhi Mahal restaurant, had earlier posted a message on social media: “Thank you to everyone for checking in. Sadly Gandhi Mahal has caught fire and has been damaged. We won’t loose hope though, I am so greatful for our neighbors who did their best to stand guard and protect Gandhi Mahal. ... Don’t worry about us, we will rebuild and we will recover.”

The message continues, “Gandhi Mahal May have felt the flames last night, but our firey drive to help protect and stand with our community will never die! Peace be with everyone. #JusticeforGeorgeFloyd #BLM”

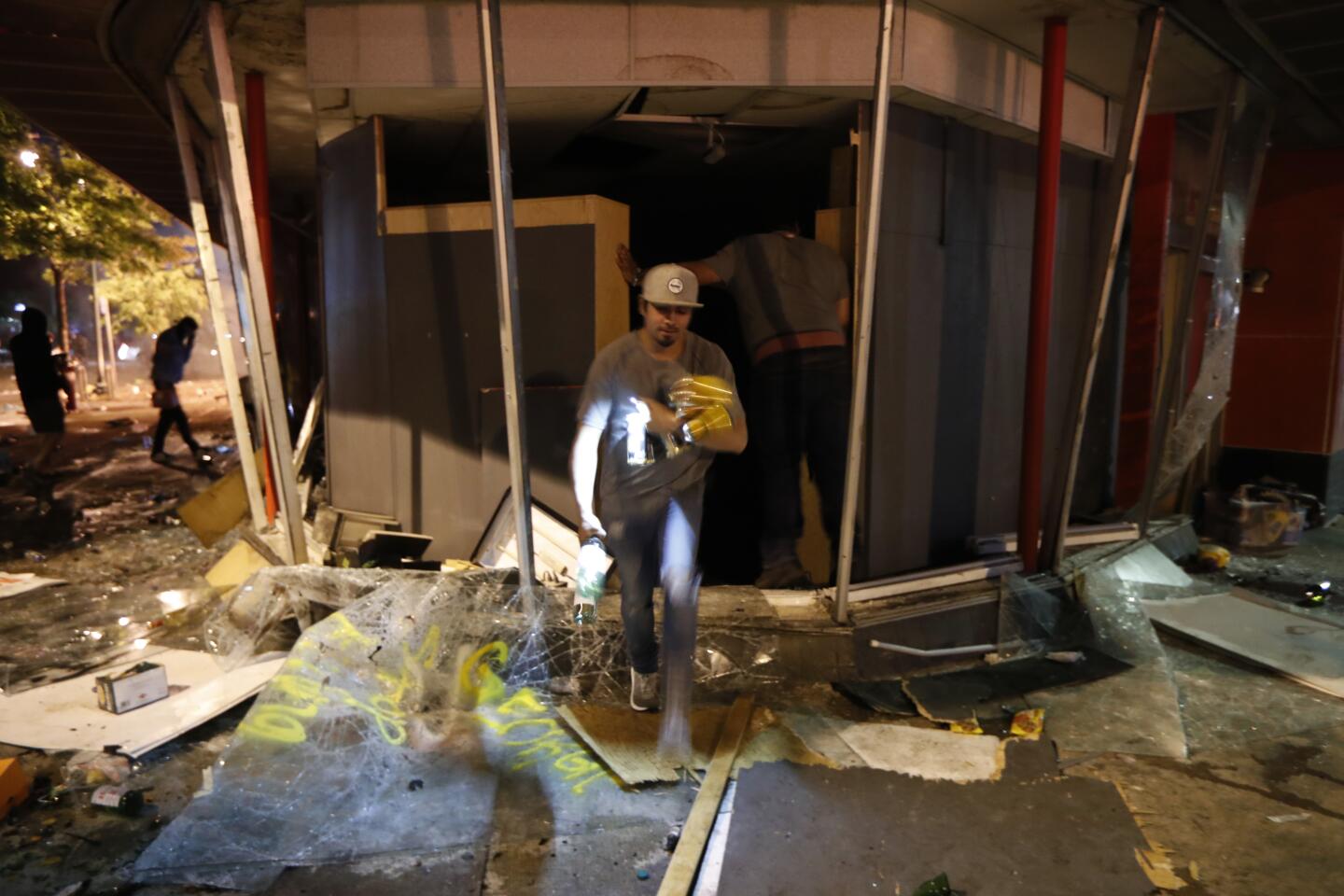

Some tried to protect their businesses against looting by taping messages of solidarity in their windows, including “African owned business” and “We support our small diverse and minority businesses.” But those windows were broken overnight, too, leaving security guards sweeping up the shattered glass Friday.

Minneapolis restaurant Gandhi Mahal is damaged in the protests over George Floyd’s death. The owner’s family expresses solidarity with protesters.

“We never expected this,” said Elmi, who like other merchants has also been buffeted by the lost business and travails the coronavirus has brought.

He noticed that even East Lake Street’s mainstays were looted, including Ingebretsen’s, a Nordic bakery and meat market where residents line up at Christmas to buy lutefisk, pinnekjott, and yulecake. Elmi and his restaurant supplier, Mohammoud Abdi, said the damage reminded them of their youth in Somalia, where they watched militants roam and the government lose control of the country.

“We don’t have law and order,” said Abdi, 47. “This is not helpful to George’s family.”

Liban “Lee” Alin surveyed the damage with dismay. Alin, 30, who works at a local homeless shelter, grew up in the area before settling there with his wife. As a child, he prayed and studied the Koran at the makeshift mosque Elmi created at the back of Hamdi Restaurant. But as an adult, he had been racially profiled by white police officers who live in the suburbs.

“I agree with why people are upset,” Alin said, “but don’t destroy the community. Who knows if the businesses are going to want to come back?”

Neighbor David Allen, 42, was among the first protesters to march to the police station Tuesday to demand that police officers be charged in connection with Floyd’s death. He said looting had become a distraction. The pub where he works was closed and boarded up Friday.

“The message is getting lost,” Allen said as he filmed firefighters with his fiancee, who owns a clothing customization business.

Allen said he had lost confidence in police and most political leaders. He predicted neighbors would band together in the short term to rebuild businesses and police themselves.

“Enough is enough,” he said.

Car salesman Eli Aswan, 50, was moving several dozen cars Friday from the lot he has owned on East Lake since coming to the U.S. from Tanzania nearly two decades ago. A friend in the suburbs had agreed to let Aswan park the cars at his house while the dealer boarded up his office to brace against the looting.

Thieves broke in Tuesday and stole more than $17,000 worth of auto repair equipment and titles. After that, Aswan shuttered the windows and camped out in his office overnight. Early Friday, two looters carrying gas cans pried one of the boards off his window, then drifted off without breaking in. Aswan decided it was time to close up shop for a while.

“It’s too risky,” he said as he stood in the lot wearing a camouflage Minnesota cap.

Aswan has been trying to cater to customers with better credit but was rejected this week by a local financing program when he mentioned that his business was on Lake Street. He too has had conflicts with police, saying he was pulled over for running nonexistent red lights. He challenged the ticket but still had to pay a fine. He worries about his sons being profiled: One is 16; the other is 19, a computer science student at the nearby University of St. Thomas.

A few doors down, Eloy Bravo was supervising a crew boarding up the windows of his ransacked Lupita Nail Salon.

Bravo, 50, and his staff of eight had been looking forward to reopening June 1 after closing temporarily due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Looters hauled away more than $10,000 worth of supplies and equipment, including the cash register.

“We were so excited. Now, I may have to close,” Bravo said.

He started the salon after moving from his native Puebla, Mexico, 15 years ago. He initially came for vacation but fell in love with residents, who he called “kind and friendly.”

Bravo lives in the suburbs, and he was stunned Friday when he arrived to see the damage on East Lake Street.

“What did I do for people to come and destroy what I built in 15 years?” he said.

Bravo has had break-ins before. He remembered years ago when there was enough crime in the area that police added bicycle patrols. But he thought that had changed.

Neighbor Lauren Johnson spotted Bravo and pulled over to help clean up. Instead, he ended up helping her distribute water and snacks to passersby, many of them protesters like her.

“If you walk from one end of Lake Street to another, you’ll see all sorts of cultures,” said Johnson, 34, who was wearing an “I can’t breathe” T-shirt, a reference to what were among Floyd’s final words.

“People used to be scared of Lake Street. Now people come here for great food and music.”

But will they still come? Will businesses rebuild?

“I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Bravo said.

Down the street, Elmi watched as firefighters put out the blaze next door to his restaurant. It wasn’t clear what could be saved. They cordoned off the area with yellow police tape, like a crime scene.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.