War claims a revolutionary radio station in Syria

AMMAN, Jordan — The news broadcast finished and Salah Abed began to dismantle the equipment: There would be no other broadcast that evening — and maybe never again — from the Radio Fresh station in the Syrian town of Kafranbel.

The town had been an icon of uprising and the radio station was its voice to the world. Activists relied on the station, along with skits and videos that frequently went viral, to lampoon President Bashar Assad and the international community’s inability to stop the carnage of Syria’s civil war.

But this week, Assad’s forces, bolstered by Russian warplanes, advanced two miles away from Kafranbel. It would soon be in their hands, another defeat for a battered opposition on the cusp of losing its last bastion in Syria, the northwestern province of Idlib.

“We counted 25 airstrikes that day alone. Dozens of rockets, dozens of mortars, dozens of artillery… we knew it was our last day,” Abed said in a phone interview.

As the Syrian civil war approaches its ninth year, Assad, having subdued or pushed out the rebels from other parts of the country, has turned his sights to Idlib. Since December, a withering government offensive has clawed back dozens of towns and villages in the rebel-held province. Kafranbel is one more, but for the civilian activists of Radio Fresh and many others, its fall means losing an emblem of the revolution.

“Yes, Kafranbel has symbolism for all Syrians, for every person worldwide who knows of Kafranbel,” said Abdullah Klido, a 37-year-old activist and Radio Fresh’s executive manager.

It was more than a year into the uprisings in 2012 when Kafranbel, a quiet farming town known for its bountiful fig and olive harvests, was seized by rebels. It quickly became famous for another reason: its activists, including Raed Fares, a one-time real-estate agent turned opposition organizer.

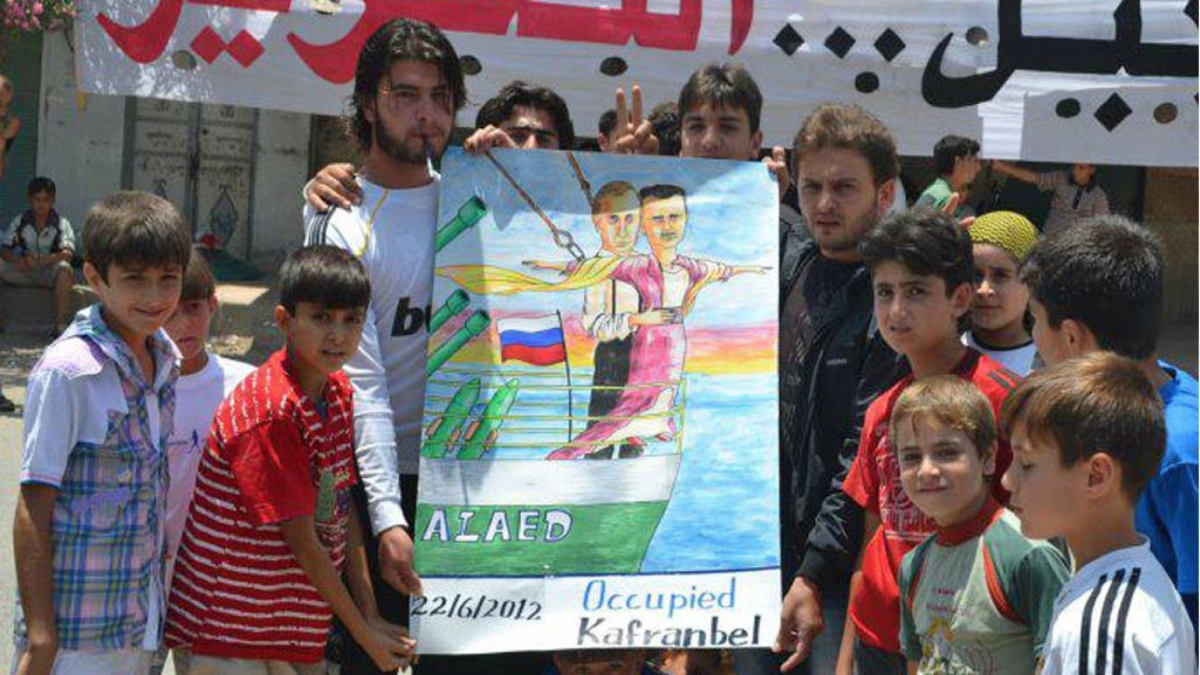

Among their other activities, Fares and his colleagues designed dozens of placards, written in English and often channeling pop-culture references to mock Assad, his allies, the jihadists growing in power within the rebel ranks as well as world leaders reluctant to protect Syrian civilians.

One poster portrayed Assad as a contestant on a show called “Terror’s Got Talent.” (Russia, Iran and the world are the judges.) Another depicted then-President Obama as a Captain America-like figure with fake muscles deflated by a pin-toting Russian hand.

Radio Fresh was another of Fares’ projects, one he started in 2013 with support from the State Department to broadcast news, airstrike warnings and music. The latter made the station a target of Al Qaeda-linked groups commandeering the insurgency against Assad. Most espoused an austere interpretation of Islam and considered music — not to mention the democratic ideals Fares and others spoke of — as sacrilege. They stormed the radio station in a bid to put it off the air.

Despite threats to Fares and others, Radio Fresh continued broadcasting, defying the ban on music with sounds of barnyard animals, including goats, chickens and cows, played as a prelude to newscasts.

But the trajectory of the war, with Russia deploying its military in support of Assad in 2015 and other world powers unwilling to continue backing the rebels, had put the opposition on the back foot, even as it empowered its most extreme elements.

Rebel enclaves in Homs, Aleppo, southern and eastern Syria fell to successive Russian-backed government campaigns. Soon there was only Idlib left, its fate hanging on a tenuous cease-fire deal between Russia and Turkey — the latter is the rebels’ top supporter — that often broke down.

Meanwhile, jihadists consolidated their power over Idlib, making the activists of Kafranbel and Radio Fresh increasingly seem a relic from a time of hope in the Syrian revolution. In November 2018, Fares and a colleague were driving back from Friday prayers when gunmen peppered their car with bullets, killing both men.

“Raed wasn’t just a person. He represented the revolutionary principles we had all agreed upon, for which we were ready to sacrifice ourselves,” Klido said. “There was fear of being assassinated, of being bombed and shelled — but that doesn’t mean we were backing down.”

Less than a year later, Damascus, losing patience with Turkey, renewed its campaign to recapture parts of Idlib and take the M4 and M5, two strategic highways meant to be opened during the cease-fire.

As the Syrian army advanced in Idlib, Russian and Syrian warplanes paved the way in a devastating barrage. In May 2019, the Radio Fresh building in Kafranbel was struck by what Abed said was a cluster bomblet. Its cadres instituted an emergency plan, moving equipment and transferring personnel to Radio Fresh stations in other parts of Idlib that were closer to the border with Turkey, even as Kafranbel emptied of its residents.

“My family left after a Russian missile fell behind our house. Almost everyone left, but I stayed behind,” Abed said. “We could still do our work, covering the attacks and reporting on movement of warplanes in the air.”

But worse was to come. In mid-October, the strikes, which before would target Kafranbel once or twice a day, escalated to be more than a dozen. Drones and reconnaissance flights made any movement within the town dangerous. A few weeks later, Radio Fresh’s main building was leveled by Syrian army helicopters dropping barrel bombs, makeshift ordnance made by stuffing explosives and metal detritus into barrels. More residents escaped, joining a flow that had grown to almost 1 million refugees fleeing towards the Turkish border, said the U.N.’s Office for Humanitarian Affairs on Thursday.

Kafranbel was now a ghost-town.

“We moved to another building. We kept its location a secret and made sure no one knew where it was,” Klido said.

And still the Syrian army kept advancing.

“It was very hard to report on the losses. All those areas which had been liberated by the blood of honest boys… we mourned each loss, some almost as much as we mourned Kafranbel,” Abed said.

By late February, the army had reached a village adjacent to Kafranbel. The barrage had become so intense that even getting food supplies from other nearby areas was perilous.

On Tuesday night, Abed and the last remaining crew in Kafranbel finished packing the equipment. They went home, gathered what little belongings they had left, and returned to the station again.

“The hardest thing was to say farewell to our houses at night, not to see them properly, or feel them,” Abed said.

“You just don’t know if you’ll ever come back to the town in which you grew up.”

By 2 a.m., as the tempo of strikes slowed down in the early morning of Wednesday, Abed and the rest of his colleagues crammed into a car and left Kafranbel. Hours later, Syrian army troops were popping selfies in the town’s shattered squares. They pressed on with their offensive, moving past Kafranbel in an offensive that on Friday killed 33 Turkish soldiers.

Though it is no longer broadcasting from its hometown, Radio Fresh continues.

“We’re sad because we’ve lost a home. But Raed Fares wasn’t clinging to bricks, but to ideas,” Klido said.

“As long as we’re here, the idea is here to stay.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.