Russian Tatars feel threatened as Putin pursues nationalist agenda

- Share via

KAZAN, Russia — This month, school officials across Tatarstan were ordered to trim by half the number of hours of optional lessons offered in the Tatar language — from four a week down to two.

The directive came two years after the Kremlin ended the rights of the Russian Federation’s 85 regions, republic and territories to mandate regional language instruction in school curriculums.

The ongoing erosion of local language rights has touched off unrest in the resource-rich republic that straddles a swath of the Volga River 500 miles east of Moscow.

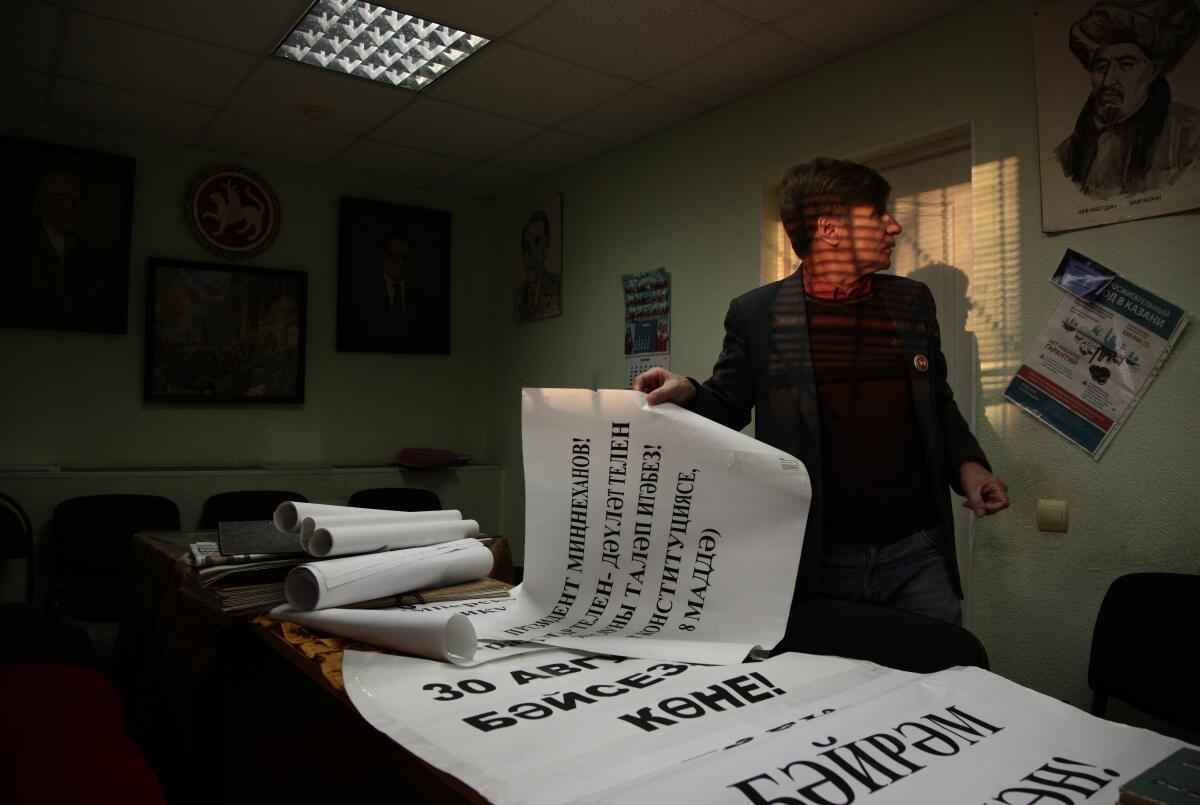

Tatar activists, including leaders of the nonprofit All-Tatar Public Center, have been fined, detained, interrogated and searched by police for demanding greater protections for the Tatar language and culture. One activist who staged a one-man picket outside government buildings has been sent twice in the last two years for court-ordered 30-day stays at a psychiatric hospital, a punishment reminiscent of Soviet Union-era tactics.

Farit Zakiev, the leader of the All-Tatar Public Center, says that Tatar leaders fear for the future of their language and the rights of their community, and they place the blame directly on Russian President Vladimir Putin.

“Putin’s actions will lead to the opposite of what he wants,” Zakiev predicted, saying that the more that Putin oppresses Tatars, the more that Tatars will resent Moscow.

In 1992, after the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Tatar center helped create momentum for a referendum on independence, which passed with 62% of votes.

Tatarstan was not granted full independence, but in 1994, it did negotiate a treaty with then-Russian President Boris Yeltsin that granted extensive autonomy, including exclusive rights to natural resources and the ability to collect taxes.

During his two decades in power, Putin has relentlessly sought to erode regional governments’ abilities to protect ethnic languages, history and cultures. He’s signed laws to nationalize the production of history textbooks and required all ethnic languages to be written in Cyrillic, the alphabet used in Russian.

Under terms of the law ending mandatory regional language study, students now have to request optional lessons for such regional languages as Tatar.

Moscow has argued that Russians — even in places where they are a minority — should not be obliged to learn a language that is not their native tongue.

The law has particularly stung Tatars, the second largest ethnic group in Russia, making up about 4% of the total population. Their language is spoken by about 50% of Tatarstan’s population of 4 million. About half of Russia’s 5.3 million Tatars live in Tatarstan, which boasts a thriving economy fed by its own oil company and military aircraft factories, as well as a new IT park on the outskirts of the capital, Kazan.

Ironically, critics say, Putin has used the excuse of protecting native Russian speakers to undertake invasions abroad. He did this in 2014, they point out, when he annexed the Crimean peninsula from Ukraine.

Putin first became Russia’s president in 2000, and the beginning of his tenure was defined in large part by the bloody suppression of a separatist revolt in Chechnya, another mostly Muslim republic in Russia’s restive North Caucasus region.

“Putin thinks he owes his political career to fighting these issues, and they are of paramount importance to him,” said Abbas Gallyamov, a former speechwriter for Putin who is now a political consultant in Moscow. “When they arise, he springs into action, sometimes unnecessarily.”

Putin’s fear is deeply personal, Gallyamov said. He once called the breakup of the Soviet Union the “greatest tragedy of the 20th century,” and he has not forgotten the attempts by Tatarstan and Chechnya to claim independence from Moscow as the Soviet Union was crumbling nearly three decades ago, Gallyamov said.

Under Putin, the Kremlin sees ethnic diversity as the potential root of the country’s collapse, so it pushes for greater centralization, said Natalia Zubarevich, the director of the regional program of the Independent Institute for Social Policy at the Higher School of Economics in Moscow.

“They do not understand the value in diversity and flexibility and think only in terms of control and lack of control,” Zubarevich said.

Russia’s language law took Tatars by surprise, said Rimma Bikmuhametova, a journalist in Kazan who covers regional and ethnic issues. At the time, Tatarstan schools required students to study six hours of Tatar language a week. Today, parents must ask for a separate Tatar course for their children. Many schools do not have a Tatar teacher as thousands were laid off after the adoption of the law.

“It was the most powerful moment in the last 10 years here,” Bikmuhametova said. “People stood up and listened to what was happening and were greatly concerned.”

In Tatarstan, many saw the new law as a direct attack.

“It is impossible to convey the indignation in words,” said Mintimer Shaimiev, the first president of post-Soviet Tatarstan. Shaimiev is a revered figure in Tatarstan, having served three terms as president, during which he was a strong supporter of autonomy.

Periodic inspections by the general prosecutors pressure schools in Tatarstan to enforce the federal law.

Meanwhile, activists have drawn the ire of the local police. In January, Zakiev, who grew up bilingual in a small village in eastern Tatarstan, was summoned by police to discuss “irregularities” at a November demonstration he participated in. He disregarded the summons.

A member of the All-Tatar Public Center since 2002, he has helped organize protests that have been followed by increasingly stiff responses from authorities, including detentions and fines.

Zakiev, who once studied aviation engineering and worked for a large Soviet enterprise that produced trucks and machinery, worries that younger Tatars aren’t paying close enough attention to their culture.

Give the chance, most parents would choose to put their children in English classes before Tatar lessons. His daughter speaks Tatar to her children. But his son, an engineer, “just doesn’t understand that we might lose our language,” he said.

“We Tatars are very tolerant people,” he said as he offered guests a bowl of fresh honey from a Tatar village and sipped coffee at his kitchen table. But their tolerance, he added, may make the Tatar nation too easily oppressed.

Gallyamov, the political scientist who served in the regional administration in Bashkortostan, a neighboring Russian republic, before becoming a speechwriter for Putin, warned that tolerance now has the potential to turn into political problems for the Kremlin in the future.

“Tatars can remember such offenses for a long, long time,” he said. “Sometimes generations.”

Special correspondent Stanislav Zakharkin in Moscow contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.