How prepared is the U.S. health system for a major coronavirus outbreak?

- Share via

ATLANTA — As a deadly new strain of coronavirus spreads beyond China, public health experts are confident in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s capacity to monitor the virus and lead the effort to contain it.

“The CDC is the best of the best,” said Rebecca Katz, the director of the Center for Global Health Science and Security at Georgetown University.

But with President Trump at the helm of a chaotic administration — one that in 2018 disbanded the National Security Council’s global health security team — such faith in U.S. government expertise also comes with questions about local, state and national resources and coordination.

Will Trump, a self-described germophobe who criticized the CDC in 2014 during the Ebola outbreak, remain on board with federal health experts’ messages? How readily will Congress approve extra emergency funds? How prepared are local and state officials?

“Looking at the CDC is really only looking at half of the picture,” said Michael T. Osterholm, director of the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy at the University of Minnesota. “The front line for this is going to be in hospital emergency rooms, in workplace settings, in public spaces like theaters — and these are areas that the CDC doesn’t have a lot of jurisdiction over.”

Local, state and federal public health departments, he stressed, have long suffered from budget cuts.

“When this hits us with any real punch, public health will be the fireman, the policeman, the EMS, the National Guard, all wrapped in one,” Osterholm said. “And yet, when you look at what we invest in public health overall, unfortunately it is often on a shoestring budget.”

So far, more than 7,780 cases of coronavirus and 170 deaths have been confirmed across the globe. Five people in the United States have tested positive — two in California, and one each in Washington, Illinois and Arizona — and a total of 110 people in 26 states are being monitored for possible infection, a number that is expected to rise.

As the geographic footprint of the coronavirus expands, federal officials have struck a balance: warning the American public of the potential gravity of the situation while stressing that there is no need for panic.

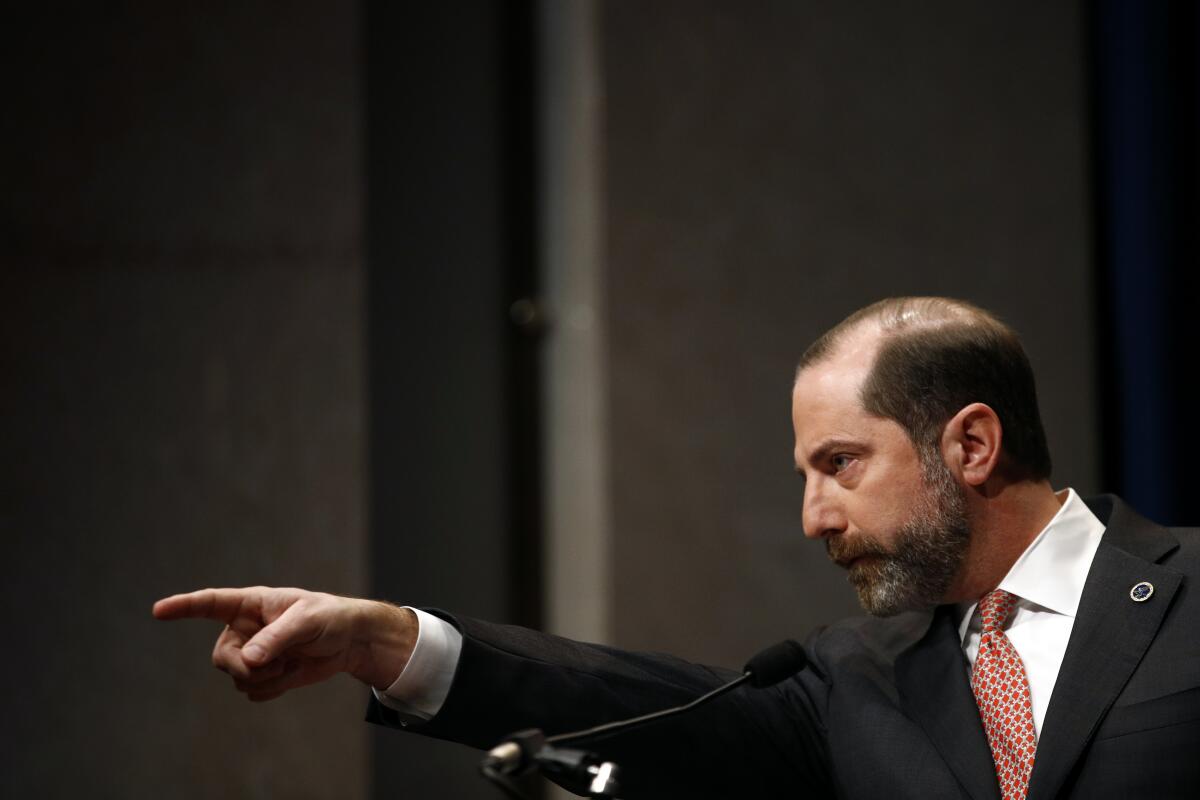

Alex Azar, the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, which houses the CDC, said Tuesday at a news briefing that experts were working to ascertain the speed of spread of the virus, its severity and the length of the incubation period. At the same time, public health departments and healthcare providers, working with the CDC, were following an established playbook for responding to an infectious disease.

The department’s emergency response arm was also assessing the level of preparedness with the Strategic National Stockpile, which includes pharmaceuticals and other necessary medical supplies, Azar said.

Though many public health experts praise the CDC for communicating a thoughtful, nuanced approach, some believe the agency should communicate a more urgent message to hospitals, schools and workplaces.

“I fear that they’re kind of getting set up to say, ‘Don’t worry, you know, Americans are safe,’” said Osterholm, the author of “Deadliest Enemy: Our War Against Killer Germs,” published in 2017. “Stopping an influenza-like transmission in a community is like stopping the wind. Go into any major emergency room in this country and they’re crowded as can be. The chance of having more transmission at a hospital or medical clinic is absolutely real.”

With flu season already well underway, emergency room doctors in Atlanta and Los Angeles are complaining of a shortage of N95 masks, Osterholm said. Due to shortages in funds, he said, hospitals have virtually no surplus or stockpiling of masks, Tyvek suits and gloves — everything health workers need in an environment with an infectious disease.

Part of the problem is timing, said Dr. Howard Markel, professor of the history of medicine at the University of Michigan.

“Very often we don’t know how deadly the virus is until many days or weeks after you should have acted,” he said. “So knocking out a home run — not too early so that you jump the gun too early, and not too late because people will die — is a hard call to make with a great paucity of data.”

Such challenges are compounded by long-standing budget cuts in local, state and federal public health.

The CDC’s funding, with inflation factored in, is about 10% lower than it was a decade ago, said John Auerbach, president and chief executive of Trust for America’s Health, an advocacy group.

After the 2007-09 recession, he said, state and local public health lost more than 50,000 jobs, many of which were not restored. At the same time, public health emergency preparedness grants have been cut by a third and hospital preparedness grants have been cut by 50%.

As a result, Auerbach said, the CDC has sometimes struggled to obtain necessary resources. During the Zika outbreak, for example, Congress did not make funds available immediately to respond, so the center had to pull back and redirect some of its emergency preparedness money to combat the virus.

For now, the CDC is asking clinical labs to send it samples for testing to ensure that the results are as accurate as possible. But soon it will roll out a system for more localized testing: The center announced Monday it is developing the diagnostic test for coronavirus into a kit format, which it plans to distribute to state health departments and public health labs in the coming weeks.

“Right now, the CDC has been able to manage, but that’s clearly not going to be a long-term solution, and the CDC knows this,” said Jennifer Nuzzo, a senior scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security.

Though a system of localized testing would be necessary as the virus spread, Nuzzo said, it is expensive work, and she was concerned about states’ abilities and resources.

“Anytime we’ve called on states to respond to an emerging situation like this, where they likely get a surge of tests that they need to do,” she said, “we’ve given emergency supplemental funding to make sure that they have the resources to protect the nation.”

Thomas J. Bollyky, the director of the global health program at the Council on Foreign Relations, said he worried about interagency coordination.

It was not clear, he said, that if the outbreak escalated Trump would appoint a special “coronavirus czar” as President Obama did for Ebola.

While the interagency response is being coordinated by deputy national security advisor Matt Pottinger, who Bollyky said is very well regarded, Pottinger is also responsible for all matters for China, as well as everything that falls in his portfolio as deputy national security advisor.

“That’s not an ideal circumstance,” Bollyky said. “You would like to see someone senior who has this job full time.”

Bollyky also said he was concerned about Trump’s previous expressed calls for visa bans, travel restrictions and quarantines — counterproductive measures, he said, that would make people less likely to report diseases and are not consistent with the nation’s international obligations.

“One would like to think that we won’t see a return to that type of rhetoric,” he said. “We’ll see.”

Times staff writer Emily Baumgaertner in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.