Young Thai boxer looks like a lollipop, stings like a bee

- Share via

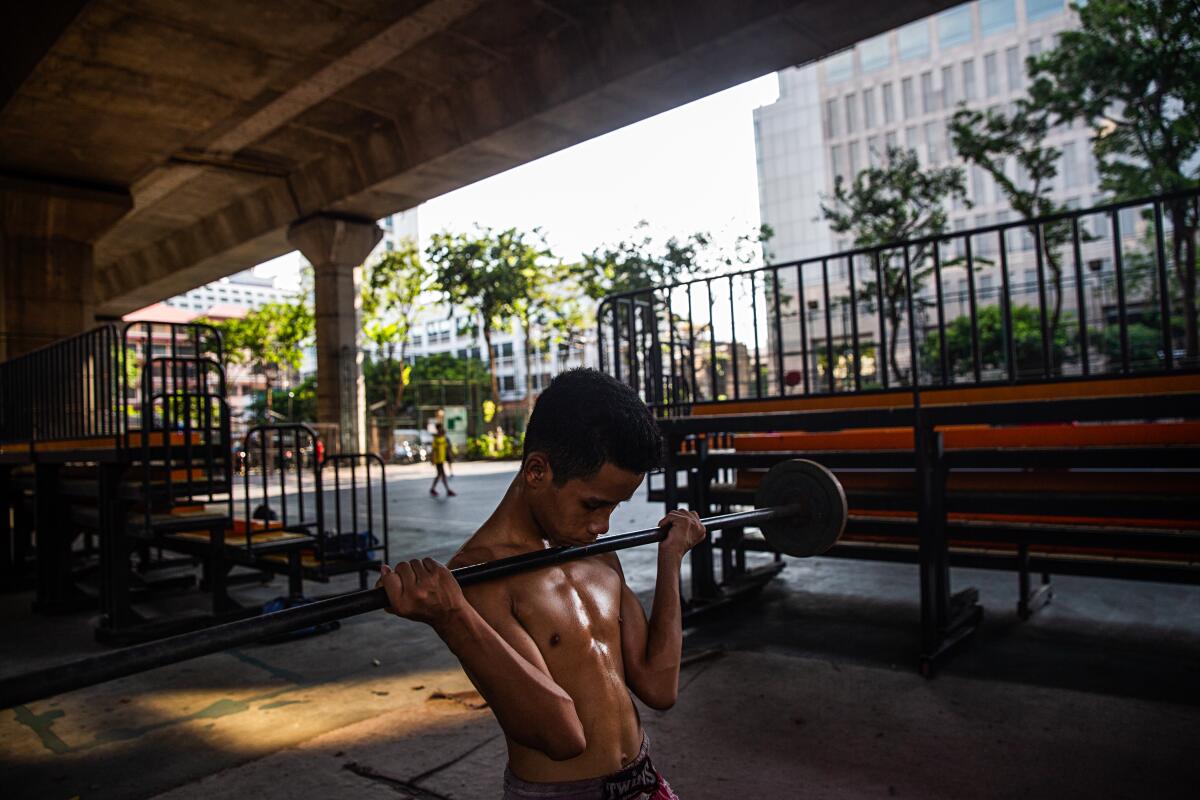

BANGKOK, Thailand — In a boxing ring under a highway bridge, 14-year-old Pheeranut Saleephol bounced between the ropes, his lean frame glazed with sweat.

The sound of punches and kicks slamming into sinewy flesh mingled with the noises of the Bangkok street. Thwap. A car honked. Thwap. A bus belched. Thwap.

Pheeranut absorbed the blows of a sparring partner who had two years and about 10 pounds on him.

“Keep your left hand up,” Tapanat Thaisamran, the man who raised him, shouted from outside the ring.

“Protect your chin.”

“Face him squarely.”

Three weeks ahead of his next bout, on a prime stage that could propel him further into the ranks of Thailand’s top young fighters, Pheeranut was even more focused than usual.

Suddenly, he whipped his right leg forward and delivered a kick to the bigger boy’s jaw, sending him tumbling to the mat.

Tapanat smiled. A trim 65-year-old with a gray buzzcut, he had been a teenage boxer himself, back in the 1960s, with a brawler’s style that suited his compact physique.

“I won more than I lost,” is how he summed up his career in Thai boxing, or Muay Thai, known as the “art of eight limbs” because fighters strike with their fists, elbows, knees and feet.

It has become a global fitness craze and a lucrative TV sport, but Muay Thai remains steeped in tradition, a font of dreams for hundreds of thousands of child fighters — many of whom enter professional rings well before they reach puberty.

Pheeranut was 11 when he first arrived at the Pathum Wan Sports Club on the back of Tapanat’s motorcycle, wearing a too-big helmet that made him look a bit like a lollipop. The coaches looked askance at the skinny, asthmatic boy who spoke little and smiled less.

“He’s small,” Tapanat told them, “but he has a big heart.”

::

Tapanat and his wife already had four children when Pheeranut came into their lives.

His mother had been their tenant, subletting a room in their apartment in Bangkok, where they worked as members of the Thai king’s extensive palace staff.

She bounced from job to job, and when she did have money, sometimes spent it on drugs instead of rent. Tapanat and his wife, Aoy Chumsri, worried she would end up on the street — especially after she became pregnant.

Pheeranut was born early and came home weighing less than 4 pounds. His mother struggled with depression, and by the time Pheeranut was a toddler, Tapanat and Aoy were raising him as their own.

A few years later, with the blessing of his birth mother, they began thinking about adoption.

Then one day, just after 4,000 baht — about $125 — went missing from Tapanat’s room, the couple’s teenage daughter found Pheeranut’s mother with an unusually large wad of bills in her pocket. She denied stealing, and Tapanat dropped the matter. But Tapanat’s daughter was unconvinced.

“If you want to adopt him, fine,” she told her father. “But I don’t want him to inherit anything after you’re gone.”

The family put its adoption plans on hold, but Tapanat assured Pheeranut he wasn’t going anywhere.

Pheeranut, who was just starting to understand that his living arrangement was far from typical, couldn’t shake the feeling that he was still an outsider in his home.

::

Pheeranut had seen boys jogging in the neighborhood and marveled at their stamina.

“They are boxers,” Tapanat said one day when Pheeranut was about 10. “I was one too.”

Pheeranut started watching Muay Thai matches online. Immediately, he noticed that the bouts almost always ended in knockouts — the vanquished sprawled on the mat vacant-eyed, sometimes smeared in blood.

The thought of asserting himself with such force held instant appeal — much more than soccer, a sport he had to quit because it triggered asthma attacks.

Tapanat reluctantly agreed to help him. “In my heart, I don’t want him to be a boxer, but if he likes it I won’t stop him,” he said.

Pheeranut weighed less than 70 pounds, but Jamlong Jaipakdee, a trainer at a local sports club who agreed to coach him, was impressed by his toughness and creativity. Pheeranut took the nickname Sua Yim Yak, or “the tiger that doesn’t smile.”

“He can solve problems in the ring,” Jamlong said. “Just when you think he is cornered, he knows the right moves to turn the situation in his favor.”

Pheeranut’s debut, a few months after he started training, was the under-under-undercard for a heavyweight bout inside an old Bangkok stadium, where tourists filled the stands and a scrum of Thai men gathered off to the side of the ring to bet on the fights.

Nervous in the carnival-like atmosphere, Pheeranut felt his lungs tighten up. He stayed on his feet for all five rounds but lost in a judges’ decision.

“I got so tired, like I was going to die,” he recalled.

He lost his next bout too. And the one after that.

He resolved that if he lost his fourth fight, he would quit the sport. But his asthma seemed to fade away, and he won in a knockout.

::

Those first few bouts each netted him barely $10. Nearly 50 matches later, having prevailed in more than two-thirds, Pheeranut was taking home more than $100 per appearance.

For Bangkok’s underage fighters, the Muay Thai circuit is opaque and chaotic, with no official rankings and matchups set by a network of promoters and trainers. Some Bangkok arenas lacked proper scales, and Pheeranut had faced off against boys who were 5 or more pounds heavier than him.

Still, he knew he was rising in prominence because Tapanat fielded calls almost every week inviting him to compete. The promoter for his next fight told Tapanat that if the boy continued to win, he’d be placed in a televised championship match with the chance at a much bigger payday.

After every fight, Pheeranut deposited his cash in a green plastic popcorn tub that he kept in a closet at Tapanat’s new apartment.

The money accumulated. Tapanat told him to take his friends to the movies, but Pheeranut always insisted the boys buy their own tickets. Aoy occasionally folded a 100-baht bill into his pocket so he could buy a snack before boxing practice, but each night when she put his pants away the note was still there.

He told Aoy that he wanted to save up to buy them a house and a puppy.

“He still has the fear of abandonment,” Tapanat said. “I think he feels that if he’s able to buy a house, it will hold the family in place. He won’t be alone.”

When Aoy cooked dinner in the evenings, Pheeranut got up from the folding table where he did his homework and shadowed her in the tiny kitchen. One day he surprised her by whipping up a pot of pork fried rice — a recipe he’d learned from YouTube.

Cooking drew him close to the woman he called Mom. Boxing bonded him with the man he called Dad.

“He’s my motivation and my inspiration,” Pheeranut said.

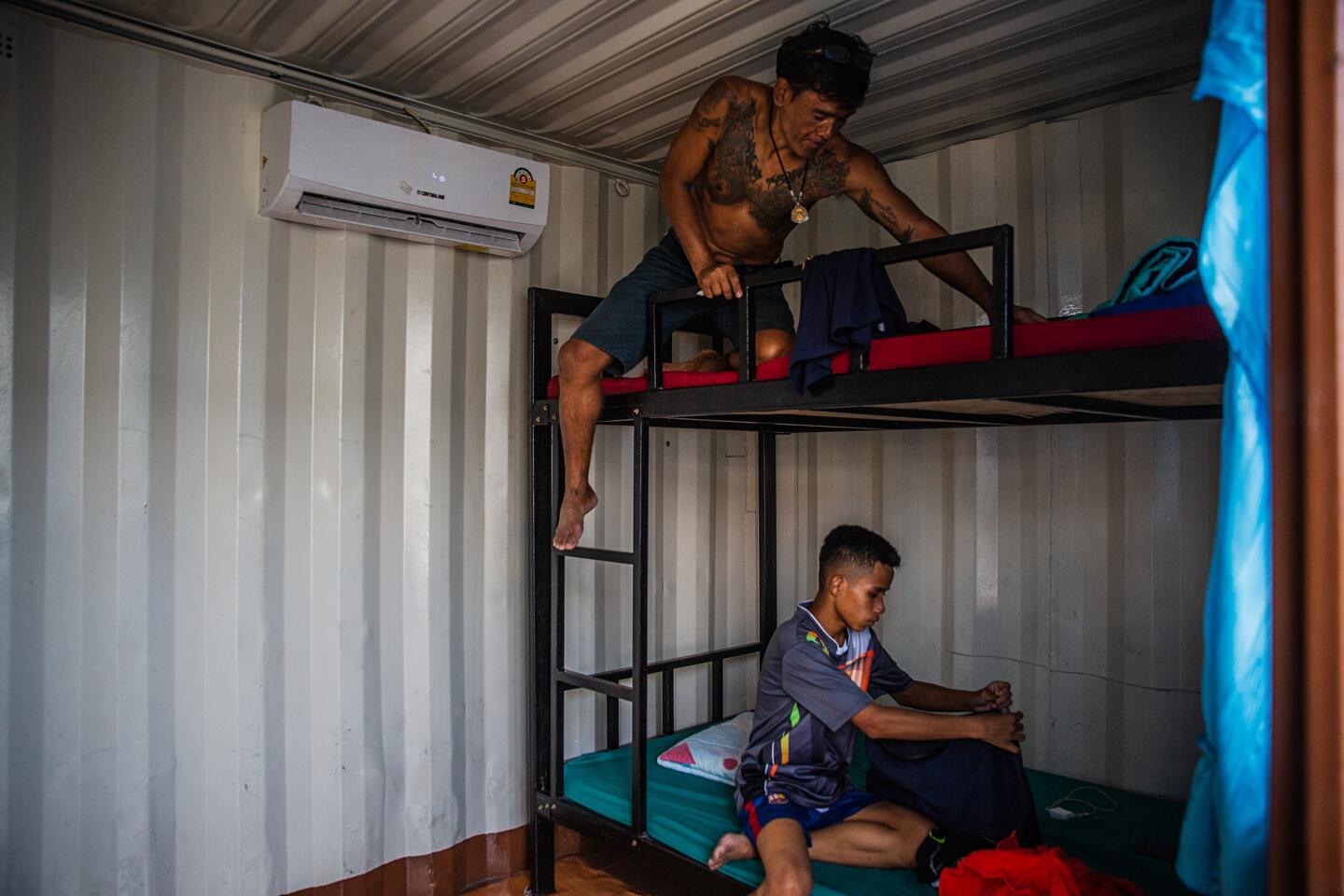

The boy sleeps on the floor on a foam mattress covered in a gray patterned sheet. But many nights, as Tapanat lies in bed next to Aoy, he hears footsteps creeping across the hardwood.

It is Pheeranut, sliding into the bed and curling up between them.

::

A few months after Pheeranut started fighting competitively, Tapanat’s 30-year-old son died suddenly of a brain hemorrhage.

Pheeranut had grown close to his stepbrother, who was transgender and had struggled with his sexuality. The night after the funeral, Pheeranut decided to go through with a scheduled fight in Bangkok. He went into the ring tired and unfocused, and his opponent landed a kick to the chin that knocked Pheeranut unconscious.

He had to be carried out of the ring. Aoy was standing over him, nearly in tears, when he came to.

Within weeks he resumed training, and resolved never to go into the ring unprepared.

Pheeranut said he rarely thinks back on that night. But the memories resurfaced almost two years later, last November, when a 13-year-old boxer died of a brain hemorrhage suffered in a bout outside Bangkok.

Video of the fight showed the boy, Anucha Tasako, crumbling to the mat after five rapid-fire blows above the neck. His death sparked a national outcry and calls to bar boys so young from fighting competitively.

Under Thai laws, any child can get into a ring with a parent or guardian’s permission, and some start training from as young as 4 in the hope of earning money. Nitikorn Sorndee, Anucha’s opponent, said he boxed to pay for his education. After the fight, he wrote on Facebook: “I’m very sad, but I have to do my duty. … If I don’t knock him out, he’ll knock me out.”

Pheeranut had never met either boy, and when he and Tapanat watched the clip, both agreed the referee should have stopped the bout sooner.

“What happened to Anucha,” Pheeranut said, “it’s very unlikely that would happen to me.”

::

Every so often, Pheeranut would ask Aoy: Is it happening? Did you talk to the office?

The other children had shed their reservations and had begun to see the boy as their flesh and blood. Aoy resumed the adoption application.

Finally, they got word that the papers would come through in August. Pheeranut would officially become their son.

“This is really what matters for him, because this is what he’s always wanted to be,” she said. “He keeps counting down the days.”

In the meantime, he kept fighting.

On a humid morning in April, the day before his big bout, Pheeranut and his coach climbed inside Aoy’s gray pickup for the two-hour drive to the scruffy beach town of Pattaya. They pulled into the parking lot of an arena with a giant figure of a boxer poised over the street corner with the word “MAX” printed on his trunks.

Launched in 2013, the Max Muay Thai network airs a slickly produced slate of fights every night on TV and online — usually Thais matched up against boxers from overseas. The mostly teenage boxers are paid based not on whether they win or lose — but how well they entertain the audience.

The next night, rowdy Australians and selfie-snapping Chinese tourists filed in to the arena to the din of hard rock beats. Pheeranut and Tapanat, who had driven separately from Bangkok, waited in a trainer’s room that smelled of liniment.

Five of the first seven fights ended in knockouts. Then Pheeranut’s picture flashed on a 20-foot video screen as his name boomed over the crowd. The screen parted in the middle and he stepped out wearing a robe, blue shorts and a mongkol, a traditional headband made of rope.

Music blared as he climbed into the ring, bowed to the spectators and removed the mongkol, hanging it in his corner. At 92 pounds, he and his 14-year-old opponent were the smallest fighters of the night.

In the first round, the two boys jabbed with their elbows and fired their knees like pistons into the other’s stomach. Sweat flew off their skulls as each blow landed, drawing cheers from the crowd.

Sitting in the front row, Aoy held out her phone to take photos. Her hand was shaking.

The bell sounded again and each boy retreated to his corner. The first round had been roughly even. Jamlong squirted Pheeranut with water as another trainer rubbed his thighs.

“Use your legs,” Jamlong said, slapping Pheeranut on the back. “Be tough.”

Standing below the ring, Tapanat folded his arms across his chest but resisted the urge to bark instructions.

The referee gave the signal and the fight resumed. Pheeranut held off a flurry of kicks before going on the attack. He pinned his opponent on the ropes, pummeling his torso with punches.

The referee separated the two for a moment, but Pheeranut kept up the onslaught — left kick to the stomach, right kick to the stomach, right again, then a left-right punch combination.

Another punch to the face was all it took. The larger boy dropped to the mat, and less than a minute into the second round the fight was over.

Pheeranut raised a fist as the crowd roared, then ran to his fallen opponent, a medic leaning over him. Assured the boy was conscious, Pheeranut jogged back to the corner, and knelt down to say a quick prayer, pounding his gloves on the mat.

Tapanat was already on his way backstage to meet him. Pheeranut climbed down and walked past the first row, where he found his mom beaming and clasped her outstretched hand.

Finally, he smiled.

Special correspondent Wilawan Watcharasakwet contributed to this article.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.