What treasures might be lost in Iran if the worst happens?

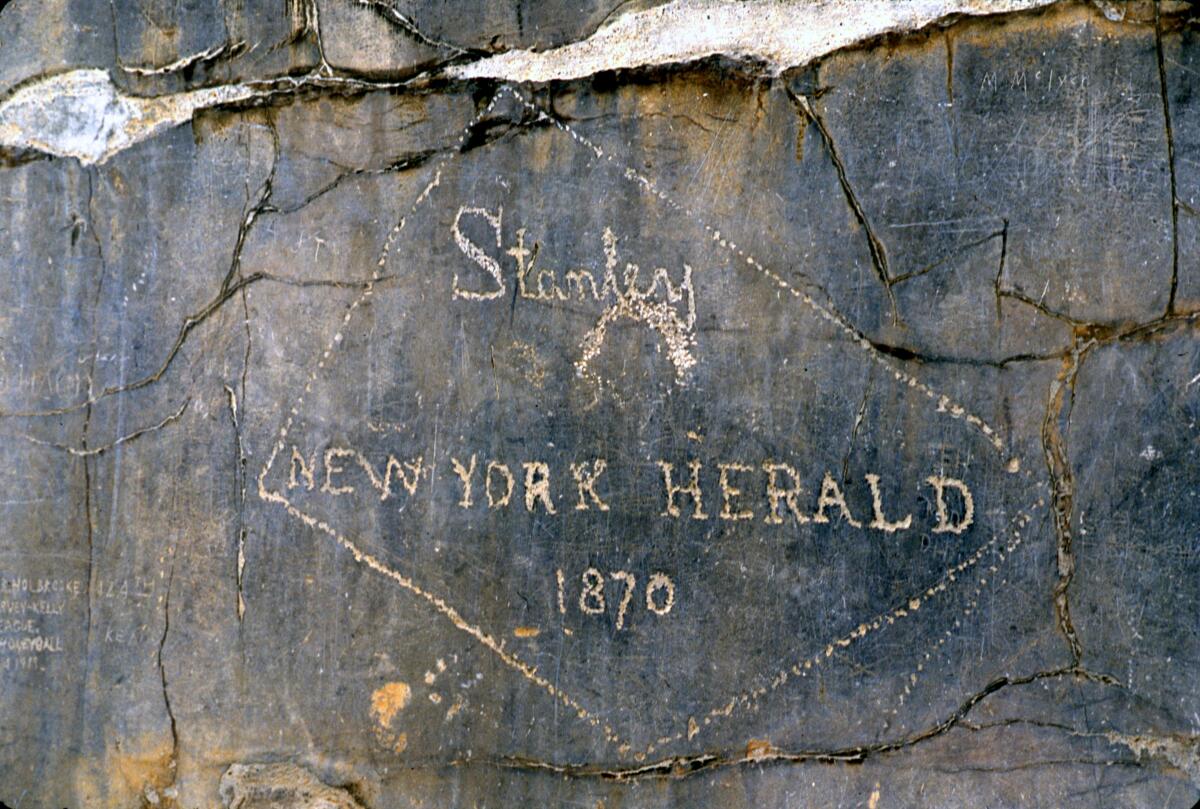

After the week we’ve seen, there’s no telling what might come next in Iran, no telling exactly what Iran’s leaders or ours have in mind. But I can tell you what I’ve been thinking about: two strange, wonderful weeks in 1998, when I got to explore that country, camera in hand, during a brief upswing in Iranian-American relations.

Along with countless lives, the global treasures I saw then are what’s at stake now.

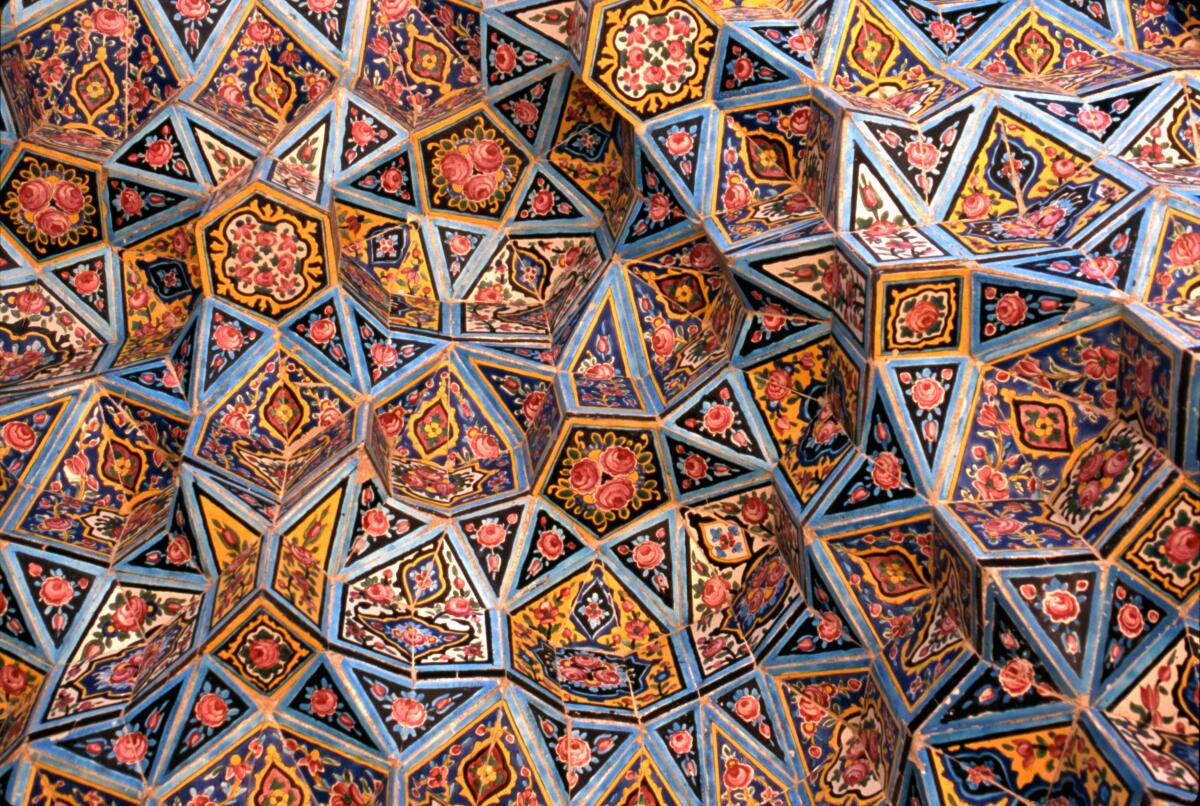

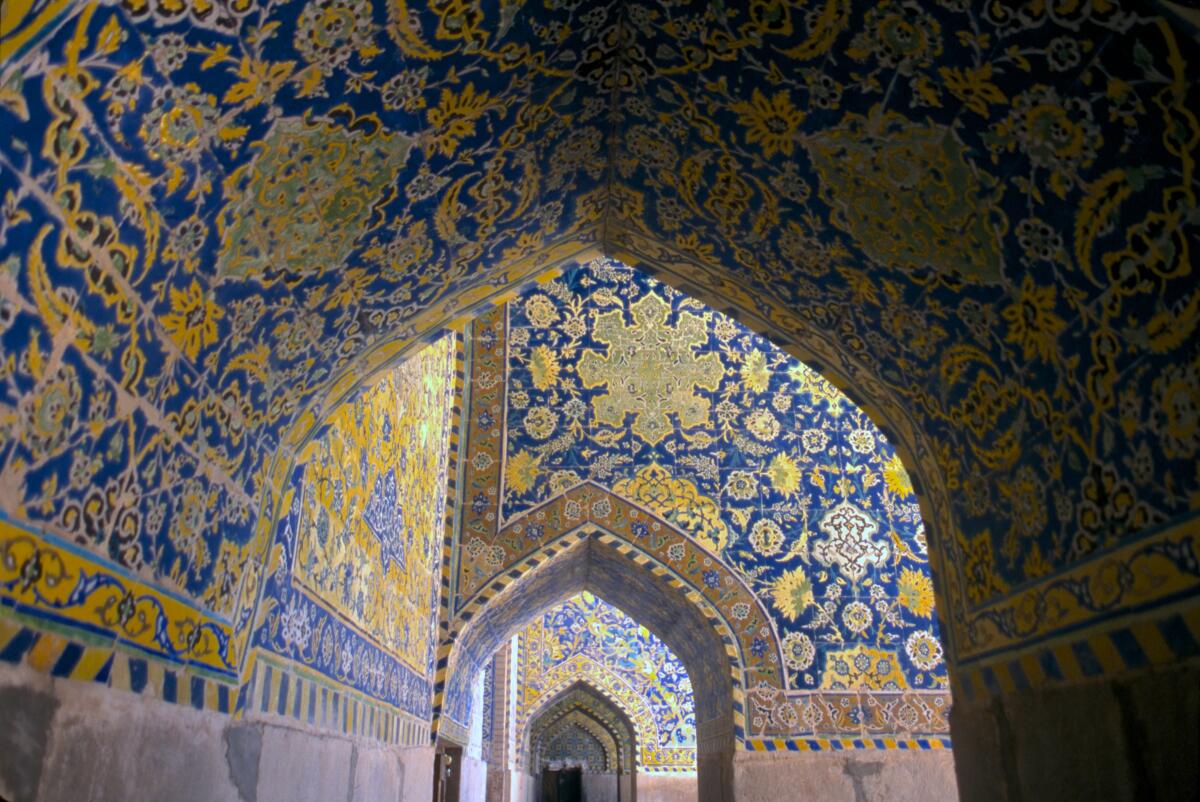

So I dug these slides out of the back of the garage and had them digitally scanned. They show glimpses of Iran’s vast cultural legacy — especially the 17th century architecture in Isfahan — and reveal how hopeful many of us were for a brief spell a generation ago. They also remind me of the vast distances, in words and deeds, that can separate a nation’s leaders and its people.

“Down With USA” said the foot-high letters at the entrance to our government-controlled Homa Hotel in Mashhad, a message that echoed the bad old days of 1979, when Shia Muslim fundamentalists chased out the ruling shah (who had been more or less installed by the U.S.), took over Iran, seized 52 American hostages and held them for 444 days.

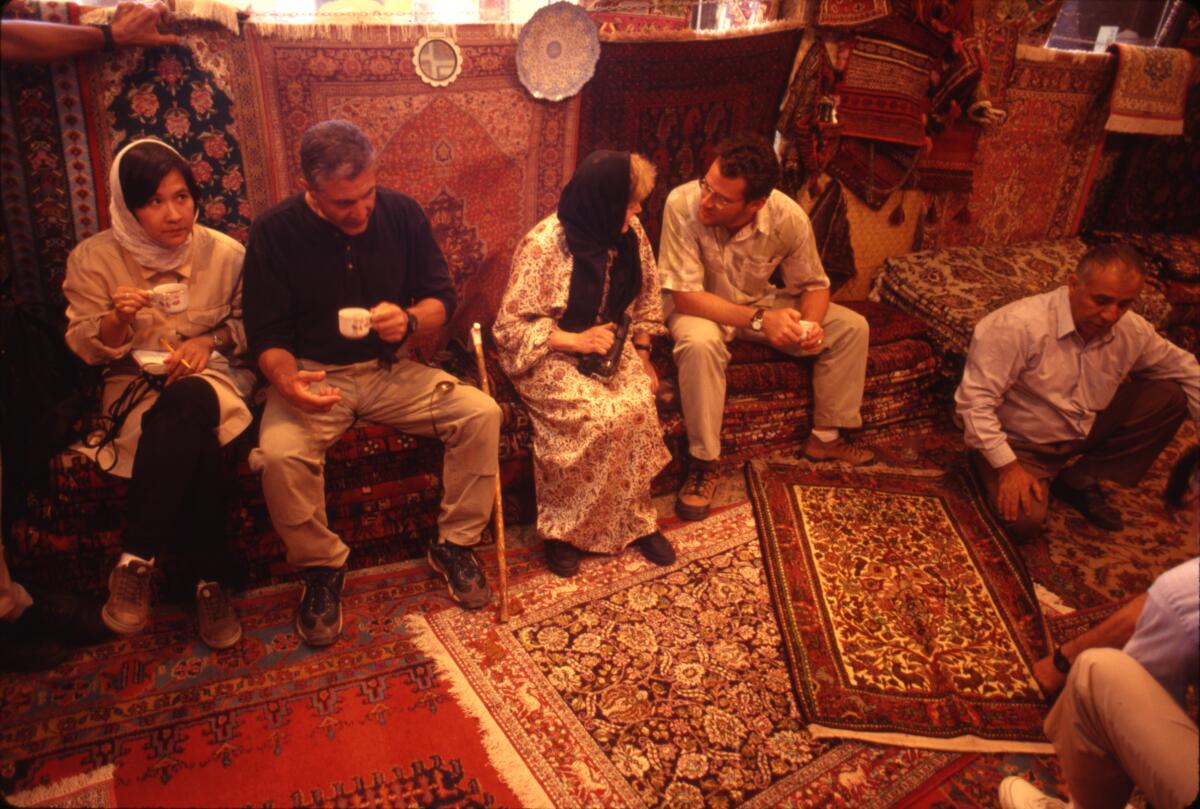

Beneath that message stood a doorman facing our party, which included seven American tourists, two reporters, one U.S.- and one Iran-based guide. We were eight men and three women, who had covered themselves with loose wraps in deference to Muslim custom.

I wondered, given the sign above, what our host might say.

“Good afternoon, sir,” he said in English, grinning broadly. “Please, this way.”

At the reception desk, beneath a glowering portrait of the late Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a clerk said, “Welcome, sir, please,” and offered another encouraging smile.

They were just two among dozens of Iranians in Mashhad, Tehran, Shiraz, Isfahan and beyond who would feed us, answer questions, tell jokes, explain the poetry of Rumi and the empire of Cyrus the Great, point out the subtleties of mosque architecture and remind us of the life-or-death importance of desert hospitality.

We didn’t see all of the UNESCO World Heritage sites in the country — there are 22 or 24, depending on how you count — but we got an eyeful.

Who traveled and why

What sort of American tourist went to Iran in 1998? The curious, affluent kind, as I wrote in my story at the time. Three were doctors, one was a retired defense analyst, one a graphic designer. Two were Jewish, one African-American. The ages ranged from 50 to 78. I was sorry to see, checking names this week, that most of the seven have died. So has Hooman Aprin, our Iranian-born, U.S.-based guide.

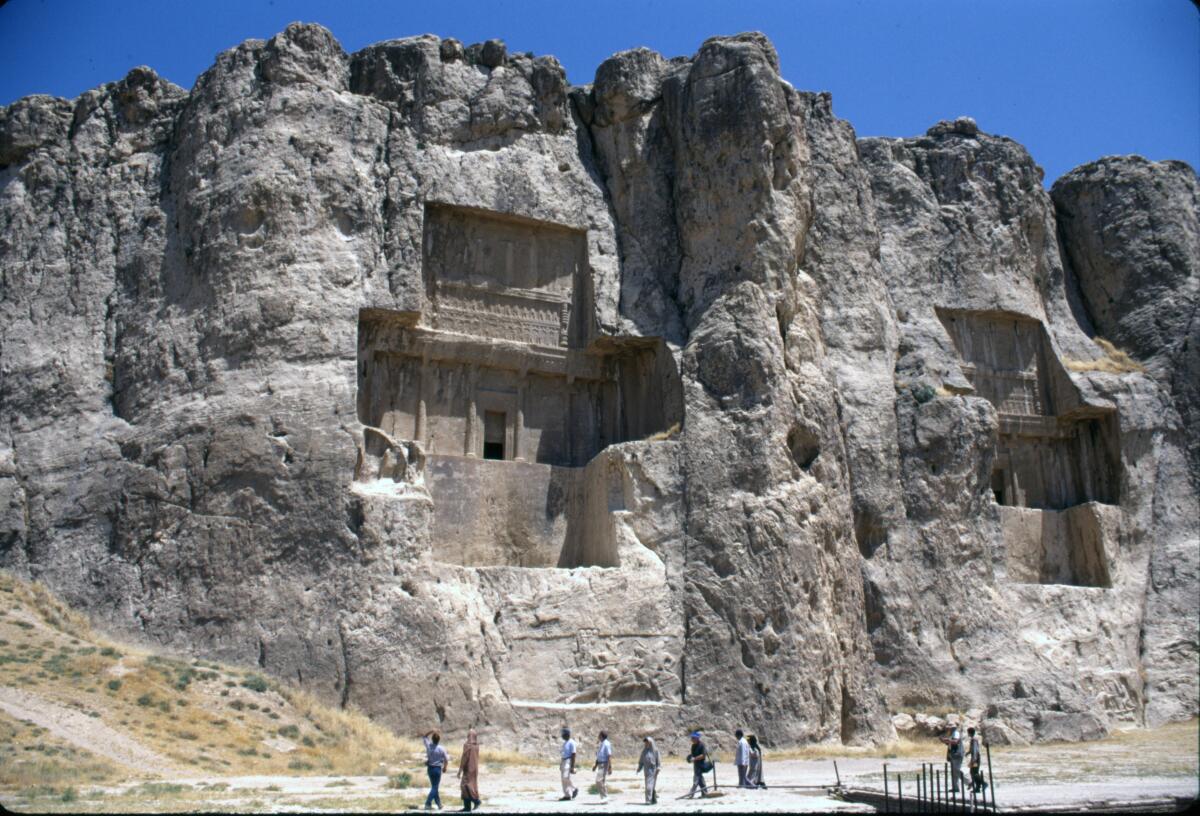

Traveling mostly by chartered bus across perhaps 2,000 miles of the country, we roamed the ruins of Persepolis, a UNESCO World Heritage site founded by Darius I in 518 BC and full of grand buildings and exacting sculptures.

We did the same at the remarkably intact adobe ruins of Bam, a key trade-route stop from the 7th to 11th centuries. Bam is also a UNESCO site. But it looks different now. Five years after our visit, a 2003 earthquake killed more than 26,000 people and destroyed most of the old citadel. (There has been some reconstruction since then.)

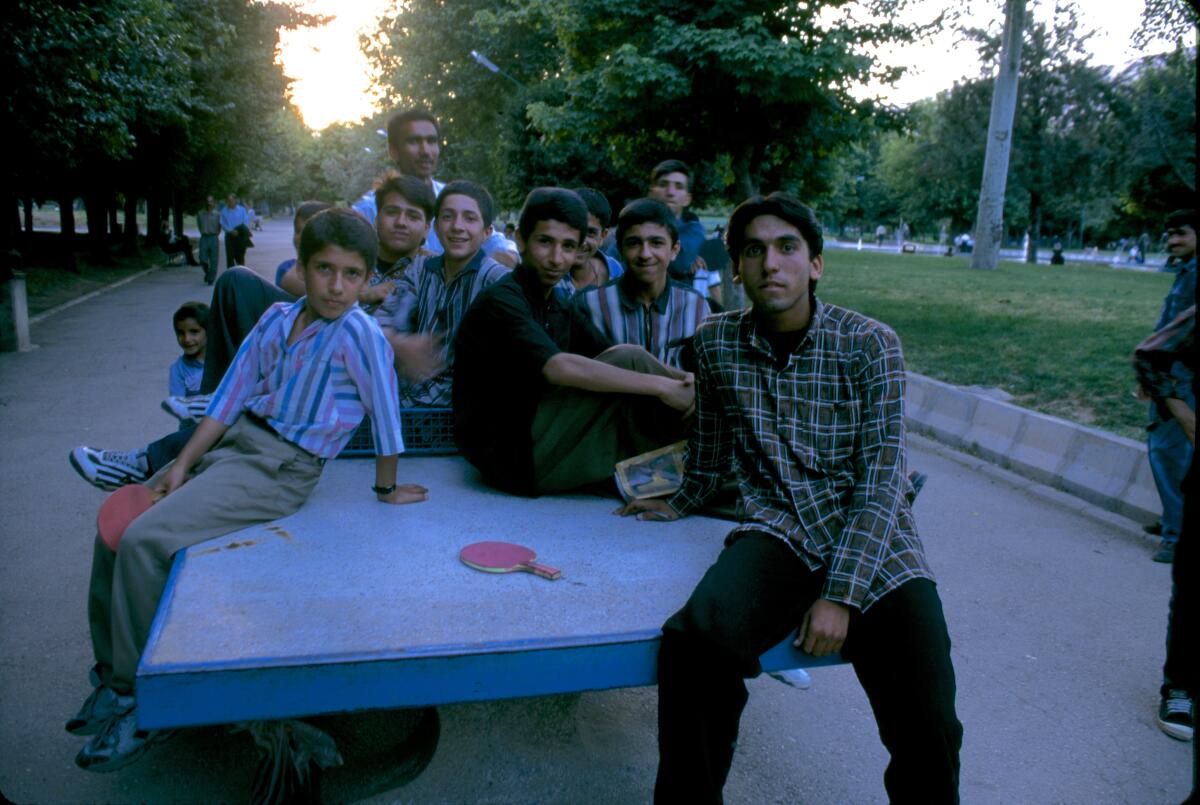

We filed through a Mashhad mausoleum honoring dead from the Iran-Iraq war. We sipped tea under the elegant architecture of Isfahan, haggled at bazaars, played table tennis with locals in a public park in Shiraz, inspected a Zoroastrian tower of silence in Yazd, and got only a fleeting sense of the sprawling, modern urban jumble of Tehran (which is not entirely different from the sprawling, modern urban jumble of Los Angeles).

There were many kebabs, and there was no alcohol.

Except for the gravedigger who hailed us from a distance and called out a mocking “Heil Hitler!” we got hearty welcomes almost everywhere. (One of our guides immediately ran over to give the gravedigger a talking-to.)

I’ve heard similar reports from many other American travelers, who have been discouraged but not banned from travel to post-1979 Iran. In fact, a handful of tour operators have made Iran a specialty, including Distant Horizons in Long Beach and Geo Ex in San Francisco, which ran my long-ago trip.

“They were among the most friendly, welcoming people that I’ve experienced anywhere, and it was specifically because we were American,” said Jean-Paul Tennant, chief executive officer of Geo Ex, who visited Iran in 2013. “They’d tell us, ‘The people of Iran are different from the government of Iran. And we have cousins in Los Angeles!’”

When the current crisis flared, Tennant said, Geo Ex had about 20 people scheduled to go to Iran in the spring. Now, he said, “We’re in wait-and-see mode.”

The U.S. State Department’s official advice: “Do not travel to Iran due to the risk of kidnapping and the arbitrary arrest and detention of U.S. citizens.” The U.S. government considers Iran the world’s worst state sponsor of terrorism. Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, who succeeded Ruhollah Khomeini in 1989, is still in charge, nearing age 81.

Meanwhile, President Trump has changed course on the question of whether our military might target Iranian cultural sites, causing many worldwide to worry for Iran’s 80 million civilians and its World Heritage sites.

One of those worrying is Jason Rezaian, the Washington Post correspondent who was seized by Iranian authorities in July 2014, convicted of espionage and imprisoned until his release in January 2016. His book “Prisoner: My 544 Days in an Iranian Prison,” details the ordeal, including the 72-day imprisonment of his wife, Yeganeh, who was born and raised in Iran.

“The [Trump] administration loves to claim that it’s committed to a free and prosperous Iran and that it’s deeply concerned about the fate of the Iranian people,” Rezaian wrote in the Post of Jan. 7. “Yet Trump’s willingness to target Iranian culture gives the lie to such claims.”

The Rezaians live in the Washington, D.C., area now, and are banned from Iran. If they ever return — or I do, or if someday you get there for the first time — how many of the wonders seen here will remain?

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.