Earthy but less earthly at a Vina monastery

- Share via

Finally, I could rest in Peace.

“Peace,” it turned out, was the name of the room where I stayed during a recent retreat at the Abbey of New Clairvaux. This remote Cistercian-Trappist monastery welcomes visitors needing a break from today’s frenetic world.

And, boy, did I ever need it. Just hours before our outbound flight, I was racing around the bedroom, simultaneously stuffing underwear into my bag, jabbering on the cellphone and skimming a government report. Then I jumped into the car and started to speed to the airport — with the parking brake still on.

Thankfully, all that began to fade about the time my wife, Cherilyn, and I got off the airplane in Sacramento and took the 110-mile drive north to the abbey.

Stepping out of our rental car, we breathed in the earthy air hovering over the Sacramento Valley flatlands. We were more than ready for three delicious days at a place where the priorities didn’t include rushing, talking or doing.

In the sleep-deprived, Palm Pilot-powered world that passes for “civilization,” this would be a truly radical adventure.

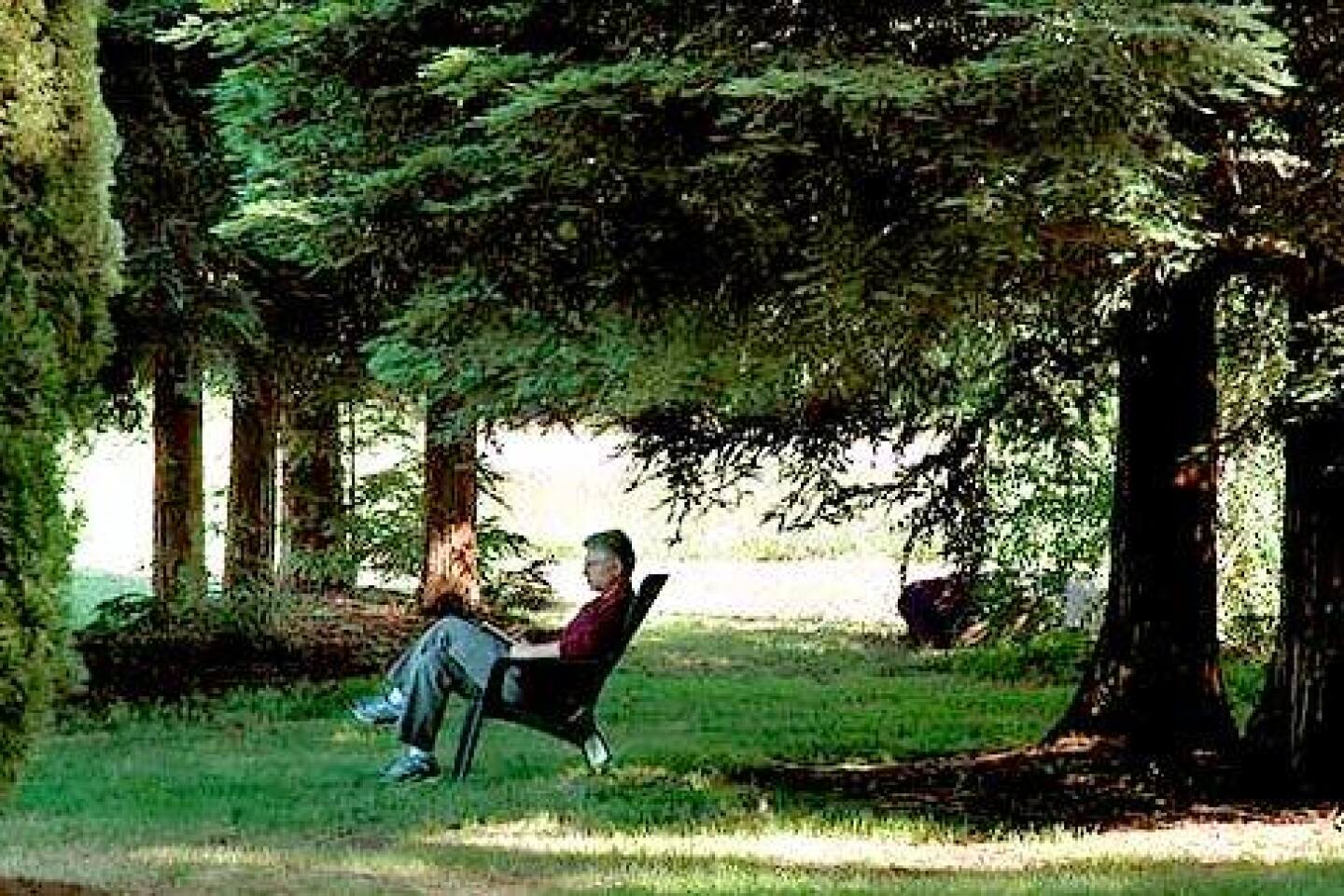

The monastery, once the personal vineyard of California Gov. (and university founder) Leland Stanford, covers more than 580 acres. In keeping with the Cistercian belief that a simple, earthly life is one of spiritual abundance, the abbey is a working farm. Most of it is covered with trees, allowing guests to wander in the dappled shadows of orchards.

Our favorites were the towering, century-old black walnut trees that spread their limbs out over the retreat facilities. Their leafy canopies gave the collection of guest cottages and rows of dormitories the feel of a small Midwest college.

At the abbey’s visitors center, just past the gate, we were greeted by Brother John. When not leading guests on short walking tours, the cheery 76-year-old scoots around the grounds in a golf cart.

Brother John’s laid-back, almost shy demeanor underscored the abbey’s mellow brand of Catholicism. In the visitors center, cinnamon-flavored creamed honey was on sale next to paperbacks on the writer-monk Thomas Merton and religious mysticism.

Brother John showed us the chapel designated for abbey guests, as well as a meditation room for the more Eastern inclined.

Then he left us alone.

*

Room to think

THE abbey’s retreats are self-guided, governed by contemplation rather than a roster of seminars. The idea is simple: Give people time and space to pray, meditate, write and wrestle with larger questions that get lost amid workplace demands and birthday trips to Chuck E. Cheese’s.In my case, this invitation to do nothing led to a welcomed collapse from sheer exhaustion.

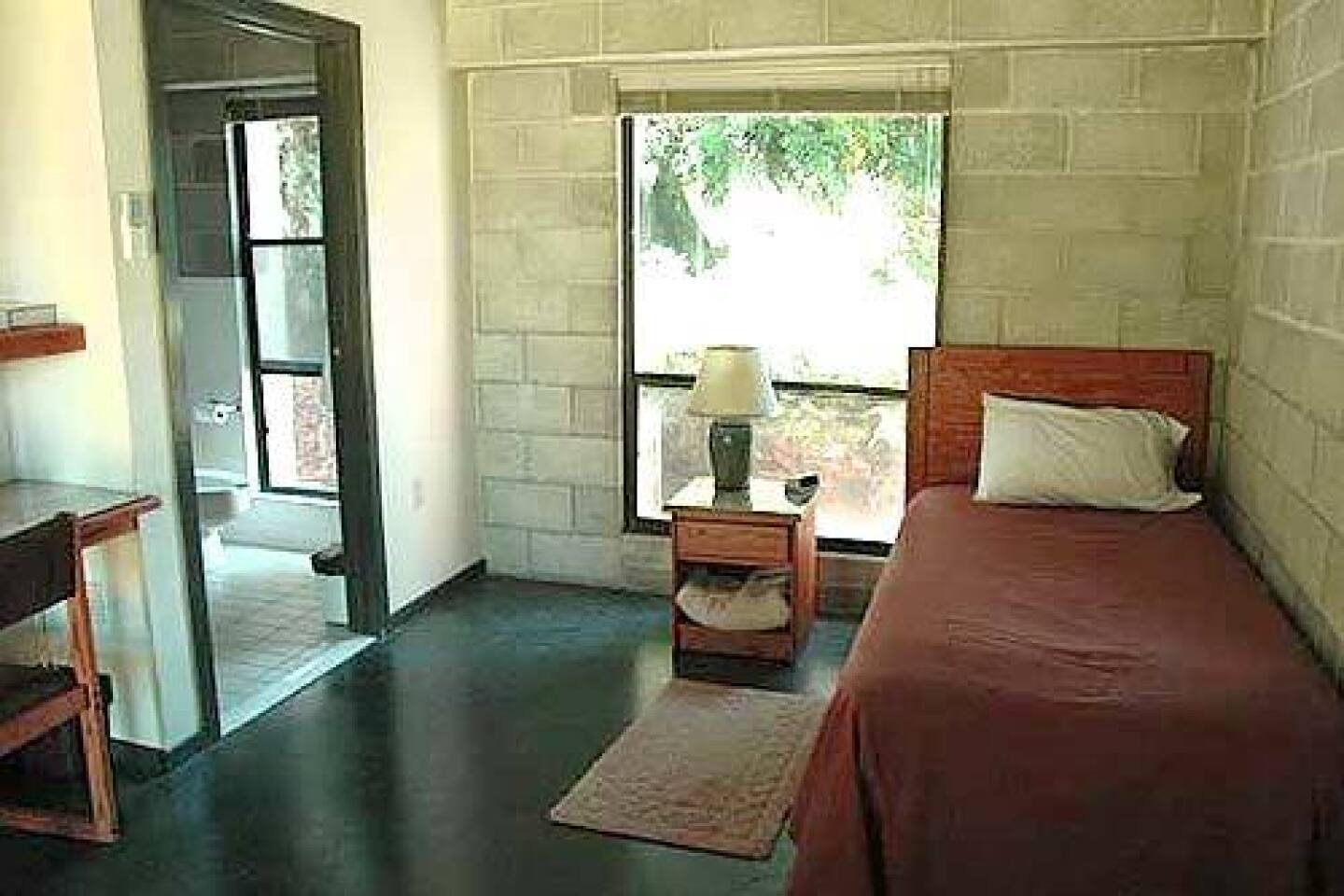

Sad but true, I spent most of my first 36 hours contemplating the pillow on my twin bed in Peace while Cherilyn was ensconced next door, aptly, in Patience. By day she wandered blissfully among the groves of trees and by night wrote and meditated.

The accommodations were simple but comfortable with inclined ceilings and private modern bathrooms. Of special significance were the built-in desks, where we pecked away at dueling laptops, like Hepburn and Tracy, on opposite sides of the same wall.

There are rooms for couples, but Cherilyn, a veteran retreat-goer, had suggested (OK, insisted on) separate accommodations. All the better to stay within the contemplative spirit of the trip, she explained.

Guests also are asked to observe the abbey’s “grand silence,” which starts after the monks utter the day’s last prayer, Compline, at 7:35 p.m., until early in the daily prayer cycle the next morning.

*

Quiet down now

During our first meal in the dining room, where guests gathered for prosaic tuna casserole or spaghetti, Cherilyn handed me a note: “Could we do total silence? Till, say, Monday morning?”My look of shock drew another scribble: “I want to stay here for a year.”

Lucky for me, the abbey has some earthbound limits. Visitors are encouraged to restrict themselves to a single four-day stay per year. With rooms for only 12 guests, there’s often a waiting list.

In the dining room, we met others on retreat and broke our silence to talk with Nancy, 54, an instructor at the Claremont Colleges who has come to New Clairvaux six times.

She described how she found solace here after the deaths of her parents. She also has walked the grounds mulling over difficulties in relationships.

“There’s something tangible in the air here that’s different from the outside,” she said.

Save the occasional friar tending the orchards or tinkering with a car, the 25 resident monks pretty much kept to themselves behind the monastic “enclosure,” a tall brick wall about a quarter of a mile beyond the retreat area. Still, their presence is felt. Three monks are on call for spiritual counseling or confession — even Brother Paul, a hermit, who emerges from his private quarters on the property as needed.

These world-shy monks have garnered a share of publicity with their plans to reconstruct a charter house using stones from a 12th century Cistercian Church in Spain. The stones were imported by publishing magnate William Randolph Hearst but forgotten after his death. The abbey rescued them from purgatorial storage at San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. The reconstruction — its first stones are already in place — will replace the monks’ existing church.

The current church serves as a sort of permeable social membrane, allowing the public in from one side and the monks from another. At Sunday morning Mass, we finally saw the diverse monk corps, from octogenarians with white beards to young initiates from Africa and Vietnam.

I have to admit, though, that my wife and I were more interested in long walks than in vespers. After I coaxed Cherilyn at least partly out of her no-talking pledge, we took long evening strolls. We ventured more than a mile to the Sacramento River, which borders the monastery.

I immersed myself in the humanistic classic “Toward a Psychology of Being,” by Abraham H. Maslow, which I borrowed from the retreat center’s small library. Then I shut myself in my room, where I began to write.

I was writing for a readership of one, me. I found myself working through some of the more difficult chapters of my life. When I needed a break, I went to the meditation room or sat under the trees. Or I imagined myself in one of the private “reconciliation” rooms off the chapel, facing the people with whom I should make amends.

By the time we left, the retreat had regenerated both of us. Our good vibe received a boost from dinner with friends at the Sacramento eatery Andy Nguyen’s, where our weekend of Catholic mysticism was rounded out with Buddhist-inspired dishes: “Universal Love Lemongrass” and “Awakening of Mind Eggplant.”

Our bellies full and minds lighter, we were ready to reenter our urban existence. This time in a lower gear and with a much better idea of when to apply the parking brake.

*

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX)

For soul searchers

Expenses for two on this trip:

Lodging and meals

Vina Abbey donation$200

Transportation

Airfare from LAX to Sacramento,

rental car, parking $490

Meals

Before and after retreat$110

Total $800

Distance from L.A. 504 miles

WHERE TO STAY:

Abbey of New Clairvaux, P.O. Box 80 or 26240 7th St., Vina, CA 96092; (530) 839-2434, [email protected], https://www.newclairvaux.org . Nine miles east of the South Street exit off Interstate 5, near Corning. Retreats generally run Mondays to Thursdays or Fridays to Sundays. Make reservations a month or more in advance. There is no charge for retreats, but a donation of $30 to $35 per day is suggested for those able to pay. The abbey also offers short guided tours by reservation, (530) 839-2243. The abbey celebrates its 50th anniversary with an open house from 1 to 4 p.m. Aug. 6.

— Ralph Frammolino

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.