Learning the ropes — somewhat reluctantly — in Chatham, England

CHATHAM, England — Rope making? Eye rolling. But I was so wrong.

I didn’t come to Chatham, about 30 miles southeast of London, to find out how to make rope. I came in search of Trixie, Jenny and Chummy — or at least the hangouts of these characters and others in “Call the Midwife,” another PBS series that, like “Downton Abbey,” has garnered a following for the poetry in its soul.

“Midwife” is set in downscale 1950s East London, and parts of the Historic Dockyard, Chatham, once an economic powerhouse from which the British Royal Navy’s ships issued, stand in for some of the series’ less-than-opulent locations.

Tours led by a costumed midwife take place on Sundays; I was here on a Monday, and no one seemed able to tell me how I could re-create that walk.

But they did tell me to get a timed ticket for the Ropery and the Ocelot, a 1962 submarine, and to make sure I viewed “Hearts of Oak,” which explains the shipbuilding process.

This wasn’t what I was here for. On the other hand, if it was good enough for King George III, it was good enough for me.

King George visited the dockyard in the 1780s and was so impressed, he invested heavily in making it the shipbuilder for the Royal Navy. He was especially impressed by the Ropery — and so was I.

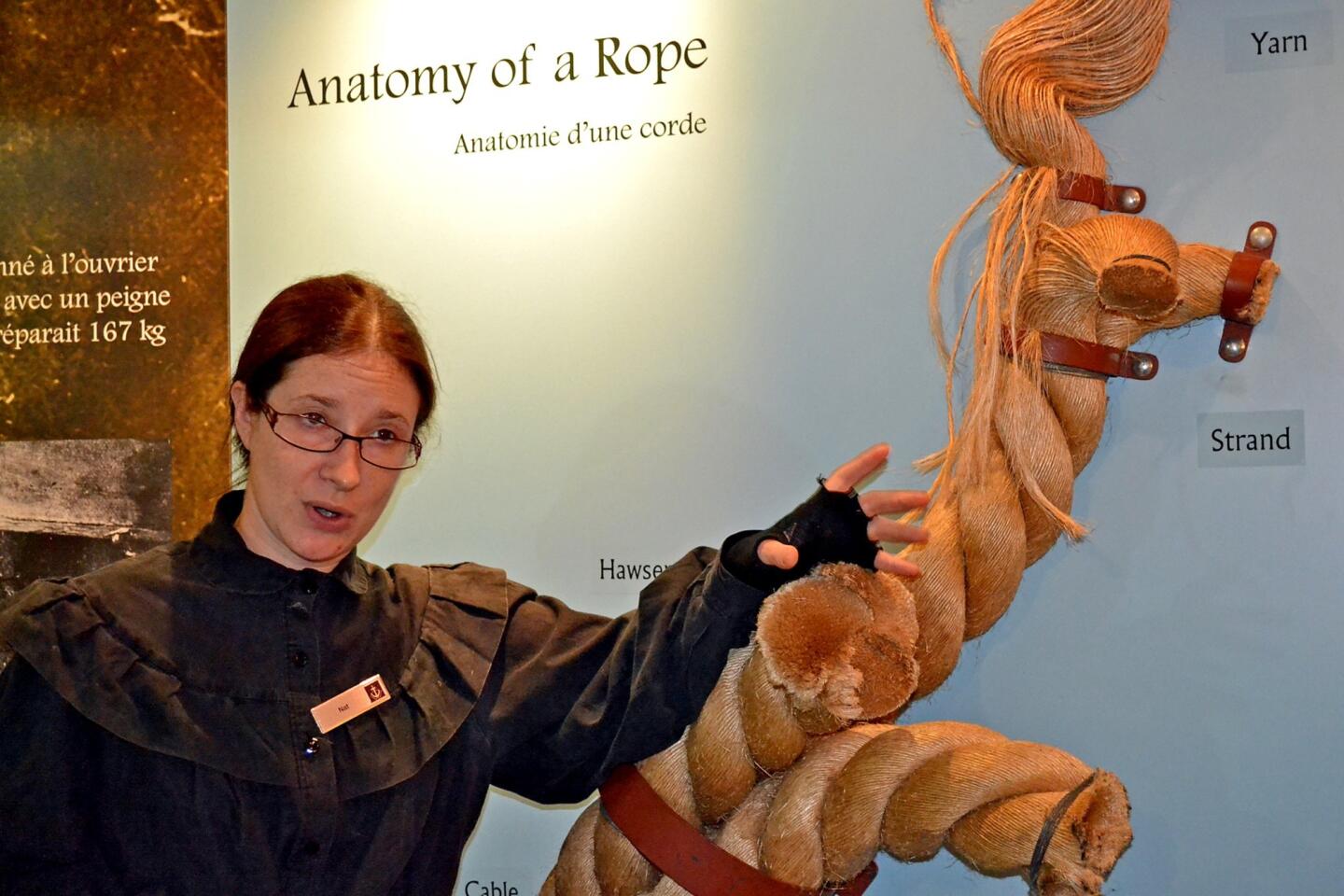

Fast forward to 1875. That’s the date from which a costumed guide spins the story of this rope-making wonder, although its production dates to the early 1600s. But in these buildings, miles and miles of ropes were made for British ships. One ship alone could use as much as 31 miles of rope.

They weren’t all called ropes, either. Each had a name to be learned — hence the expression “learning the ropes.”

The production process was as complex. The rope of 1875 was made of Russian hemp — from the stems, the guide said, because the leaves are useless, drawing a snicker from the crowd. The fibers had to be straightened and then spun into yarn — a good spinner could produce five miles a day — and then into strands and then into rope. Some samples were so enormous and heavy that you could knock on them as though you were rapping on a door. The heaviest ropes were used for the anchors.

As you might expect, smoking wasn’t allowed where rope was made. Someone who had an open flame wasn’t just in trouble for arson; he or she could be charged with treason.

Rope is still made here today, using the same methods and machinery. That’s one of the few things that hasn’t changed at the Dockyard, which closed in 1984. In its prime, it employed 10,000 people on its 400 acres; now its 80 acres contain more than 100 buildings, some of which date to the early 1700s, that are used for commercial ventures and living spaces.

It’s also home to the Ocelot, a 1962 submarine that was used by the British Navy. (The 1878 sloop Gannet and the World War II destroyer Cavalier are part of the historic warships exhibits.) The Ocelot (it and the ropery are included in the timed-ticket admission) is fascinating — but only if you’re not claustrophobic. The O class sub carried 24 torpedoes and a crew of 69 who spent as much as three months at sea.

How did these men not go mad? The quarters are tight — if you want to move through the sub, you must swing through openings with your legs in front of you — and the accommodations compact. (The last commander was 6 feet 4 inches; I’m about 14 inches shorter and felt constrained.) Water was rationed; there was enough for teeth, face and a sponge bath, but there were no showers. It was, the guide said, aromatic by the end of a long tour.

Perhaps it was the mission and patrolling the waters that kept them sane. The two periscopes — one with a wider view than the other — made me shiver, perhaps because every TV show or movie that involves a submarine has been a spine tingler. When the periscope goes up, the lights go down because it would shine out the scope. A red light does provide some illumination and some comic relief; it’s referred to as a “baby’s bum.”

That’s about as close to midwifery as I got, although after the sub, I did stumble across a couple of cutouts of the midwives on their bicycles that you can you poke your head through for a photo. The area nearby did look amazingly like some of the “Midwife” locations, but there was no explanation for that — nor mention of other filming done there, including “Les Misérables.”

That’s the puzzle of the dockyard, where the $29 admission seems pricey. I know the broad outlines of Britain’s glorious seafaring history, but it wouldn’t have been enough to lure me here on its own. It was only by luck that I had found the “Midwife” connection. In the end, I was happy to have been here, to have learned more about ship construction (especially from the fascinating multimedia “Hearts of Oak”) and to understand a bit more about what makes Britain, well, Britain.

Historic Dockyard, Chatham, will reopen in February for the season. Info: https://www.thedockyard.co.uk.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.