Do fence me in

- Share via

Reporting from McLean, Texas — Sitting along a lonely stretch of highway in the Texas Panhandle, McLean isn’t so small that you’d miss this hamlet in the blink of an eye.

It would take probably five or six blinks to blow through this town, which has never recovered from being bypassed by Interstate 40.

McLean’s heyday coincided with Route 66’s, when a seemingly endless stream of vehicles sped through. Each day, thousands of motorists drove by a large cinder-block building on the south side of the highway. Inside, a mostly female work force turned out brassieres for Sears.

The bra factory shut down in 1970, a presage of the hard times that would come with the opening of the new four-lane several years later.

“I think probably for the town of McLean, Route 66 being closed was worse,” recalls Delbert Trew, a retired rancher. “Within a month or two after it closed, McLean lost 16 businesses. They were mostly filling stations and garages.”

The town limped along, and civic leaders such as Trew realized the battered economy needed help.

“We didn’t have anything to draw people, to advertise or brag about,” Trew says of those lean years.

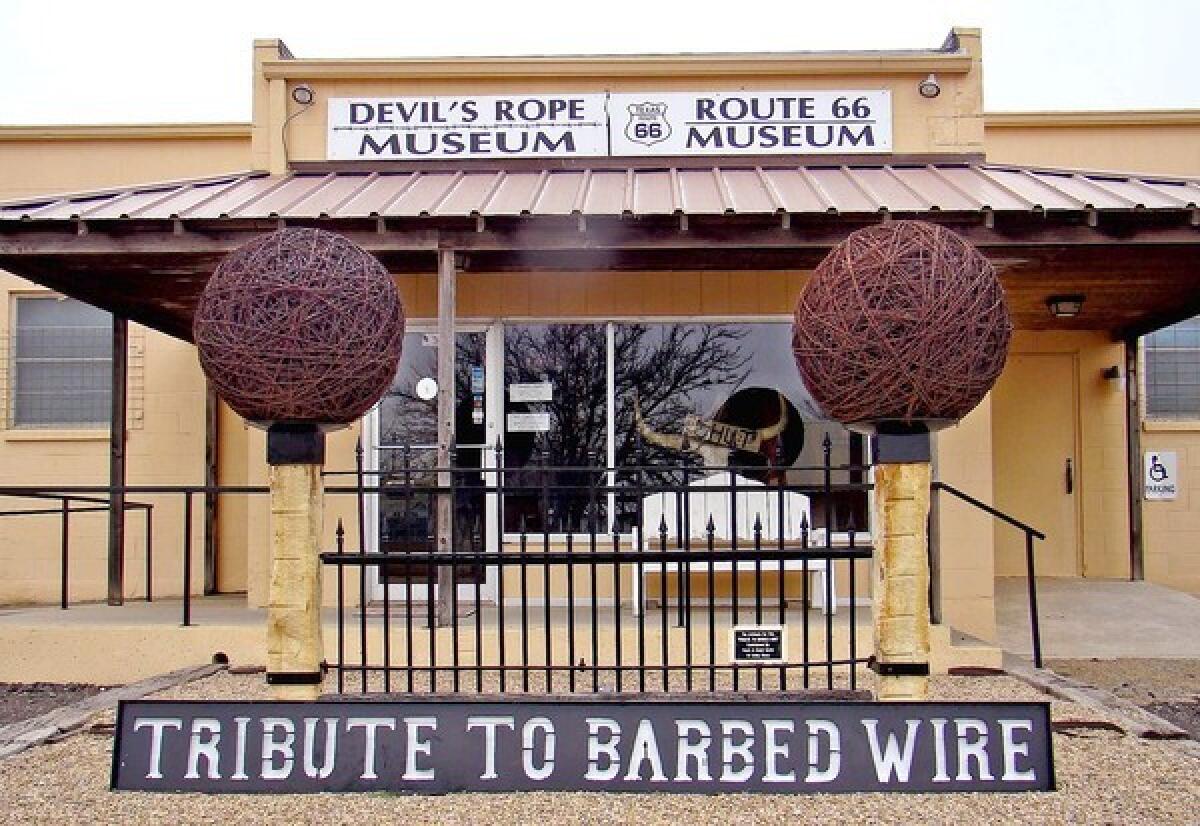

He settled on a museum, which opened in the bra factory in 1990 with a theme so obscure that it stumped a contestant — a Texan, no less — on “Jeopardy.”

“The Devil’s Rope Museum in McLean, Texas, is devoted to the history of this material,” read the Daily Double answer. The contestant just shook his head.

Host Alex Trebek provided the correct question: “What is barbed wire?”

Barbed wire? You don’t need to be on a game show to pose that question incredulously. Yet in the last 20 years, more than 100,000 people have ventured off I-40 and into McLean to visit this shrine to spiked strings of steel.

“We say barbed wire tamed the West,” Trew says.

A longtime collector of the stuff — one of many — Trew notes that before the invention of barbed wire in the 1860s, cattle couldn’t be confined on the Panhandle’s plains or anywhere else. But by stringing fences with stinging prongs, ranchers not only corralled their livestock but also defined their property lines.

“Barbed wire contributed more to the pride of ownership than any other thing,” the museum founder notes. “It stated, ‘This is my land.’”

The nickname, Trew said, is a result of the suffering experienced by cows, horses and even people when they came in contact with barbed wire. He says religious people and those he refers to as “the forerunners of animal rights people” called it “devil’s rope” and the “devil’s hatband.”

“The original barbed wire was very vicious,” he says.

Hundreds of lengths of the stuff — from those nasty, early varieties to more modern examples — are displayed. Many come from the XIT ranch, whose 3 million fenced acres once ranged across 10 Texas counties.

Stopping beside a display, Trew stuns a guest by telling him that some of the rare 18-inch strands are worth as much as $1,200. Several times each summer, collectors gather to swap wire. They even publish their own magazine.

“Our barbed wire collectors are dying off,” Trew, 77, says. “I’d say the average age is 70. Not too many young people are interested.”

Nearly 7,000 artifacts are exhibited, including a selection of “warwire,” a word Trew coined to describe the varieties used during two world wars on the battlefields and in prison camps.

“We’ve had veterans come in here and start crying,” Trew says of the barbs that confined them. He didn’t have to look far for examples; during World War II, McLean was the site of a prisoner of war camp housing about 3,000 Germans.

The Devil’s Rope Museum also archives scores of tools and implements, from pliers to post diggers. There’s even a curious-looking contraption that, when cranked by hand, makes barbed wire. The retired rancher built the machine using old windmill parts; he regularly demonstrates its use.

Obviously good with his hands, the museum’s creator brings whimsy to his favorite subject through amazing sculptures that he has fashioned from barbed wire.

Here and there among the exhibits, Trew has placed several life-size replicas of various critters found in these parts. They include an armadillo, a coyote and even a roadrunner.

Many visitors arrive by coach. They’re tourists who’ve come to see the old highway and are drawn to the former factory by its second attraction: the Texas Old Route 66 Museum. It’s another of Trew’s efforts to lure people to McLean.

Although the Mother Road museum is indeed interesting, many such places exist. There are only two barbed wire museums. The other is in La Crosse, Kan.

“It’s not near this large, but it’s very good,” Trew observes with typical Texas pride.

Trew loves sharing the lore of the land. He’ll gladly answer questions till the cows come home. Just don’t inquire about the size of his ranch.

“That’s kind of like asking how much your house is worth,” he gently admonishes a visitor. “You don’t ask a Texan that.”

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.