In Ypres, Belgium, a vibrant present stands proudly with the WWI past

- Share via

Reporting from Ypres, Belgium — “In Flanders fields,” the old poem says, “the poppies blow / Between the crosses, row on row.”

And in the middle of those fields stands Ypres (pronounced “EE-preh”), haunted by World War I but also sustained by it.

Helmets, shells and maps crowd the British Grenadier Bookshop. Cemetery tours seem to begin every other hour. Gaunt faces stare from displays in the well-designed In Flanders Fields Museum.

And every night as 8 approaches, authorities block traffic at the eastern entrance to the city, which you might otherwise notice for its 410-foot clock tower and posh chocolate shops.

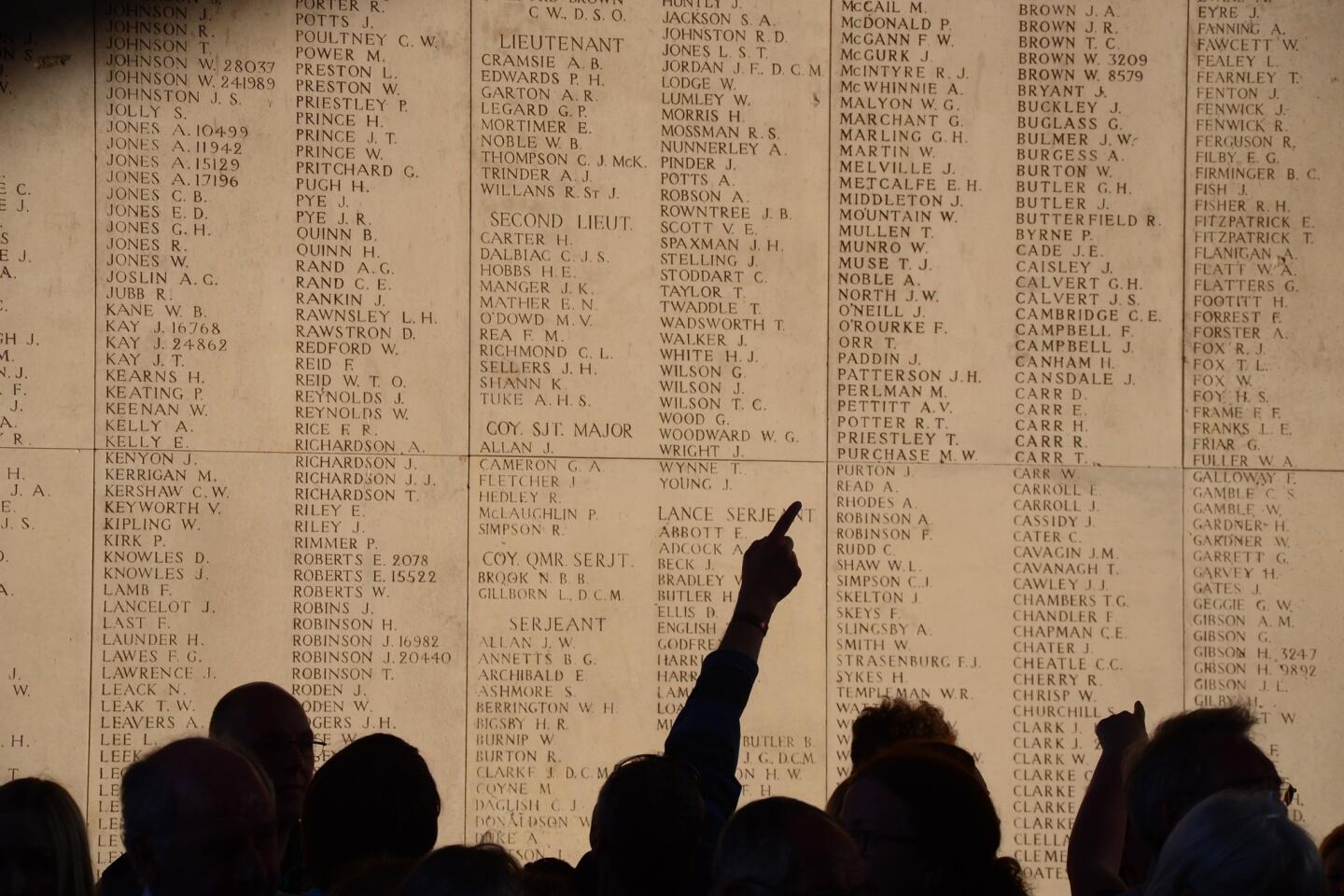

Once the road is emptied, the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing, maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission and covered with names from long ago, gets crowded and quiet. Flags are borne by shaky old men whose fathers might have died here. Wreaths of red paper poppies are laid. A team of buglers plays the “Last Post.”

Except during World War II, Ypres has repeated this ritual nightly since July 1928. The ceremony might last a few minutes on winter evenings, but on the nights I joined in early May, there were so many wreaths and people, from small-town mayors to motorcycle clubs, that the program took half an hour.

“So many names!” said a British woman, looking at the inscriptions on the memorial.

Ypres is the city the British would not let go, even after it was leveled. After the Germans quickly overran the Belgian army at the outset of the war, the Brits and their allies rushed in to fight a ghastly battle here in late 1914. Then another in the spring of 1915. Then, as both sides dug in, more battles in 1917 and 1918 — battles made doubly bitter by such innovations as poison gas, machine guns and tanks.

By the museum’s count, 550,000 soldiers died in the Ypres Salient (a military term for a bulge surrounded on three sides by the enemy) and surrounding West Flanders. Most were from the British Commonwealth, France, Belgium and Germany. However, 411 Americans are buried at the Flanders Field American Cemetery and Memorial in Waregem, 30 miles east of Ypres.

One soldier who survived the Ypres Salient was 41-year-old Winston Churchill, who briefly served in 1916 as a lieutenant colonel with British forces at Ploegsteert, not quite 10 miles south of town. Two years later, a 29-year-old German corporal named Adolf Hitler was briefly blinded outside Ypres, perhaps by a British gas attack.

Even now, farmers find ordnance. But in downtown Ypres, much is different. Though the war flattened the city (and Churchilll urged that the ruins be left as a tribute), Belgium rebuilt it in the medieval style.

Now Ypres, less than two hours by train from Brussels, has 35,000 well-heeled residents and a growing reputation as a weekend destination. Earlier this month, it served as starting point for Stage 5 of the Tour de France.

If you didn’t know better, you’d think that Cloth Hall, the building with the clock tower, has stood unmolested since 1304. It now houses the In Flanders Fields Museum, along with a well-provisioned tourist office. The view from the tower is tremendous and disquieting, and not only because of the war.

Until about 200 years ago, the town had a custom of flinging a live cat from the top of that tower. In 1955, local boosters revised that ritual into something called a Kattenstoet — a cat festival parade that celebrates all things feline, attracts tourists from as far as Japan and features a tower-climbing jester who hurls plush toy cats at the masses. They do it every three years. Next cat parade: May 2015.

Meanwhile, the Great War continues nightly. Old-timers say the cemetery tours began in the 1970s. School groups make day trips. Visitors routinely spend half the day looking at battlefields and cemeteries, half the day on bikes or motorcycles, half the night appreciating Flemish food and drink.

At In’t Klein Stadhuis restaurant on the main square, you pay $25 for a plate of rabbit and prunes in beer sauce. The Albion Hotel, opened by a local family in 2000, this year grew from 23 to 32 rooms, most priced at $120 to $200 a night. At the Juegdstadion Ieper campground, you can rent a bike for $15 a day and pedal the gorgeous 13-mile canal path to rebuilt medieval Diksmuide (which I recommend).

For about $55, you get a four-hour battlefield and cemetery tour by van.

“In here, we had gangrene,” said tour guide Andre Schaubroeck one afternoon, ushering a few of us into an old medics’ “dressing station” at Essex Farm Cemetery where doctors sorted the casualties.

“Ether. Blood. Lice. Sweat,” said Schaubroeck. “Upstairs, we had the powder of the artillery. Next door, we had the toilets.”

One doctor here was John McCrae, the Canadian lieutenant colonel and poet who wrote “In Flanders Fields” after a funeral for a friend in 1915.

“He threw it away,” Schaubroeck told us, but a reporter found it “and it was used for propaganda. And it worked.” (These same fields, however, prompted other soldiers, including Wilfred Owen and Siegfried Sassoon, to write some of the most powerful antiwar poetry of the 20th century.)

Later we stopped at Saint-Julien, where Frederick Chapman Clemesha’s haunting 1923 sculpture, “The Brooding Soldier,” stands over Canadian troops; Langemark, where tall oaks in the German Military Cemetery shade the flat gravestones of 44,304 German soldiers, 24,917 in a mass grave; and Tyne Cot Cemetery, the biggest British Commonwealth cemetery in the area.

There, among more than 11,900 headstones, most of them unnamed, we stumbled upon 40 British teens, boys and girls, in vintage infantry uniforms roaming the grid of graves, murmuring and reading headstones.

The idea, one boy told me, was to make their history lesson a more sensory experience. Whether it worked for him, I don’t know. But it worked for me, seeing all those fresh faces alongside all those old grave markers.

Twitter: @mrcsreynolds

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.