Solomon Byrd sinks into a plush beige sectional. There are crayon scribbles on the floor, diapers neatly stacked on the couch cushion and toys piled near the wall. Taysia Byrd, Solomon’s wife, is holding their 9-month-old daughter Bleu. Messiah, the couple’s 2-year-old son, is rummaging through the utensil drawer in the family’s open-concept kitchen on the ground floor of their two-story Inglewood home. An off-day during the busy football season gives the family of four a rare moment together.

USC rush end Solomon Byrd is happy here.

“Not to say I have it all,” Byrd said, “but I have everything that I wanted.”

The redshirt senior has grown into the man he prayed to be. He is a husband. He is a father. He is a college football player taking the field in front of his hometown crowd on one of the best teams in the country.

Caleb Williams put on another stunning performance in USC’s 48-41 victory over Colorado, proving he’s worthy of winning another Heisman Trophy.

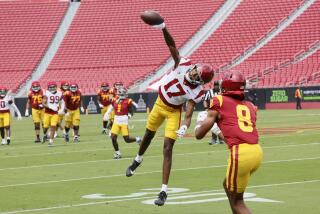

The overlapping responsibilities could be enough to crush a 23-year-old. Instead, he is “playing at a different level,” USC defensive coordinator Alex Grinch said. The rush end leads the No. 9 Trojans with 17 tackles, 7.5 tackles for loss, 4.5 sacks and three forced fumbles.

It took Solomon a year to break through at USC after transferring from Wyoming in 2022. His USC debut season was a “roller coaster” from five snaps in the season opener to starting four consecutive games to falling back as a rotational player. A pectoral injury that required surgery during the offseason threatened to derail Solomon again. USC coach Lincoln Riley wondered what the Palmdale native would do when he returned after spring ball. Solomon has blown past any expectations the way he blows up plays in the backfield.

“He’s just very much on a mission,” Riley said, “and he seems to be very inspired and pushed by his family.”

On the sideline during games, Solomon watches with an intense blank stare. Grinch said Byrd has been “all business” since arriving at USC. Generally guarded, Solomon rarely offers lengthy answers to postgame interview questions. He smiles the widest when he’s around his wife and kids.

Messiah, born when Solomon was 21 and Taysia was 20, is learning nursery rhymes. He approached visitors with an eager, curious look, grabbing at a pen and mischievously trying to hide it from his parents. He looked through the viewfinder of a camera pointed toward his father, who was playing on the floor with his sister Bleu. The 9-month-old girl only recently came into her personality. She’s not always as sweet as she seems.

“She’s wild,” Solomon said.

“When it’s time, I’m going to give her the world because she deserves it.”

— Solomon Byrd, about his wife, Taysia

Growing up, Solomon prayed for two things every day: to play college football and to meet his wife early. Both started becoming reality during his senior year at Palmdale Pete Knight High when Taysia first laid eyes on the tall guy who wore his hair in braids.

Solomon remembered the light-skinned girl with curly hair from freshman year when she was a manager for the football team, but Taysia insists she doesn’t recall Solomon introducing himself before she transferred to another school. When she returned to Knight as a senior, one of her friends played matchmaker by inviting Solomon over while Taysia was there and asked if the budding football star wanted to go to homecoming with Taysia.

He said yes.

Solomon was lightly recruited out of Knight, which lives in the football shadow of Antelope Valley power Palmdale High. He briefly considered going to junior college or giving up football completely before Dixie State started showing interest during his junior season. When Knight changed its defense to a 4-3 during Byrd’s senior year, moving the former linebacker to defensive end, he was “absolutely lights out,” Knight coach Chance Tapia said. Solomon tallied 60 tackles in nine games.

Wyoming called.

When Solomon received an offer from Wyoming, he encouraged Taysia to look into the school for herself. She applied and it was one of six schools she was accepted to. At Wyoming, where Taysia majored in kinesiology before having Messiah, Solomon was named a freshman All-American in 2019 as a redshirt freshman, appearing in 12 games with 45 tackles and 9.5 tackles for loss.

Solomon felt poised to dominate the Mountain West the following year. But he opted out during the 2020 pandemic season. If players sat out during the uncertain time, they were often labeled as quitters or players who didn’t love the game. Although football had always been a top priority, it was Solomon’s love for Taysia that superseded any game.

She has asthma, putting her at risk for severe COVID-19 when vaccines were not widely available. The risk to his family felt too great.

“If I somehow give her COVID while I want to play football and something bad happens to her,” Solomon said, “I couldn’t live with myself.”

They married with little fanfare on Sept. 12, 2020. The Byrds are not a couple for lavish romantic proposals or wedding ceremonies. They are instead holding out for a family vacation; Solomon wants a tour of Europe, Taysia talks about a trip to the Caribbean. They marked their third wedding anniversary during USC’s bye week and the date was noted on a custom whiteboard calendar reading “The Byrd Family” hanging near their kitchen. Over the sink, a large sign reads “and so together, they built a life they loved.”

They balance football and family. Taysia stays home with the kids during the day and wakes up throughout the night to feed Bleu. Solomon wakes up at 5 a.m. for lifts and stays on campus all day for practice, meetings and meals. If he’s lucky, he gets home around 7 p.m., roughly an hour before Bleu goes to sleep. Messiah rushes toward the door when his father arrives each evening.

“We handle our business and that’s what makes our household run smoothly because there’s no crossover,” Taysia said. “I never want to be that person to get in his way of his extra work or try to fill up his time when he could be doing something for football.”

Taysia tells her friends that being a mom is the most challenging and rewarding thing you’ll ever do. When Solomon entered the transfer portal, he committed to Georgia Tech before flipping to USC. Coming home was a big help for Taysia, who could rely on family and friends for support.

This season, taking both kids to games at the Coliseum feels like a team sport in itself. Taysia’s aunt attended the first two games of the year, helping handle the kids as well as check in on Taysia’s needs, but Taysia went solo to the night game against Stanford. She texted her aunt that she wouldn’t try the one-woman show ever again.

While they both envision continuing to grow their family, Taysia, who was one of four kids, is mindful of the physical and emotional toll of being a mother, especially one whose partner has such a demanding schedule. The day after Bleu was born, Solomon left for Las Vegas to play in the Pac-12 championship game. Balancing the newborn, recovering from childbirth and caring for Messiah with Solomon absorbed in the most critical part of the football season was Taysia’s most difficult moment.

Hearing Taysia recall the difficult time hurt Solomon, who acknowledged he didn’t even realize his wife was struggling.

“When it’s time, I’m going to give her the world,” Solomon said, “because she deserves it.”

Even with an offensive lineman’s arm wrapped around his neck, Solomon kept driving forward. Pushing the lineman around the edge on third-and-21 during the fourth quarter against Arizona State, Solomon swiped his right hand at the ball, knocking it free from quarterback Drew Pyne. Romello Height jumped on the fumble.

Solomon buried his face in his hands while running toward the sideline. The simple gesture holds a significant meaning for Solomon.

“Anguish built up inside, I got a heart filled with pride,” he wrote on Instagram about his celebration. “So I cover my face to hide the pain in my eyes.”

Solomon does not reveal many things easily. Instead of explaining his celebration verbally, he prefers to let the carefully crafted Instagram caption do the talking. He mentions personal issues and deaths in his family that contributed to his up-and-down season last year, but doesn’t offer details.

The fourth of Shalaunda Byrd’s six children, Solomon has always been a laid-back personality, she said. He lives up to his name, which means peace. On the field, he embodies his middle name, Uriel, which means flame of God.

Solomon grew up in a football home. Shalaunda’s uncles Malcolm, Manfred and Kenny Moore played at USC. Solomon and his siblings loved trying on Manfred’s Super Bowl ring from his stint with the Raiders. Solomon always excelled at the sport, but sometimes bumped heads with youth coaches. During elementary school, a coach told him to leave the field if he didn’t want to follow directions. Seeing her son walking away with his helmet on, Shalaunda intervened.

“I said, ‘Oh, no, no, no, no, you don’t give him the choice!’” Shalaunda said. “Get your butt back over there.”

While working as a nurse, bus driver, waitress and masseuse, Shalaunda remained an active presence in her children’s lives. She was Solomon’s team mom at every stop until high school. She was strict, especially for Solomon and his older sister, also named Shalaunda, who played basketball at Florida A&M and is playing professionally overseas. They were her two toughest kids to raise, but for good reason, Shalaunda added.

“It don’t take this much to raise a nobody,” Shalaunda said of her message to Solomon. “You are a somebody, son.”

With finances tight among the six kids, Solomon was always money-wise, Shalaunda said. When she gave each of her children $5 for a trip to McDonald’s, Solomon would insist he wasn’t hungry and pocket the money instead to only later ask his siblings for bites of their burgers. He sold items on a reselling app to scratch together extra cash and collected bottles and cans to recycle for money to buy food.

“I kind of went through it at a young age, mentally, physically, emotionally, everything,” Solomon said. “I think that’s probably why I had kids so young because I’ve kind of lived three lives already.”

Solomon avoids digging through the old memories. They break his heart sometimes, he said. Before a game at Wyoming, Solomon knelt down to pray when he was overcome by memories of that kid in Palmdale who rose from the hot desert dirt to start for a Division I football team. Tears streamed down his face.

He made it, he thought to himself.

Messiah and Bleu are still too young to appreciate what their dad is doing on the field. Solomon racks up sacks, drops runners in the backfield and covers his face in celebration, but cheers from thousands are nothing compared to hugs from two in particular. The handoff from Taysia after each game is Solomon’s most important play every week.

“I’m holding them,” he said, “it’s like, this is what you do it for.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.