John McKay and Tommy Prothro took USC-UCLA rivalry to new level in mid ‘60s

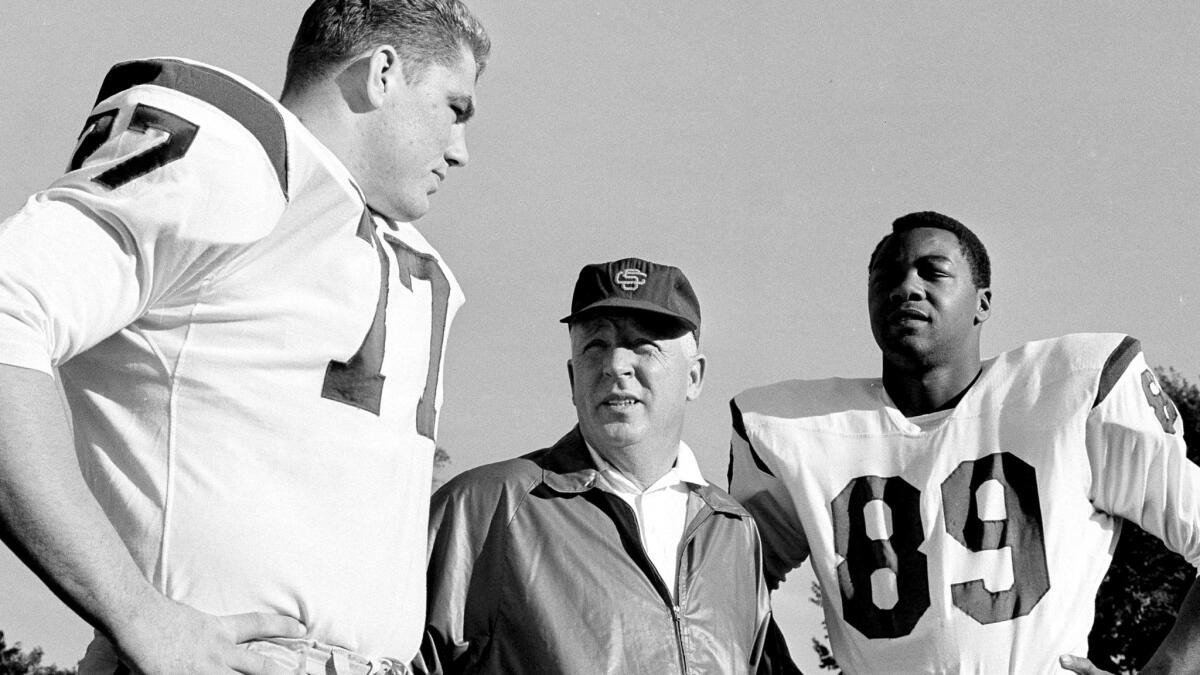

USC Coach John McKay with All-Americans Ron Yary, left, and Nate Shaw before a practice on Dec. 13, 1966.

The bus headed east from Spokane. The airport was to the west.

UCLA players were perplexed. They had not played well in defeating Washington State that day in 1967, and Coach Tommy Prothro was far from pleased.

“We started looking at each other, knowing the bus was going the wrong way,” said Gary Beban, UCLA’s quarterback. “We crossed into Idaho and the bus stopped. Tommy stepped on the ground, looked around. He got back on the bus and said, ‘Idaho is a state I have never been in, now I have.’ ”

The team then headed for the airport.

Prothro did things his way.

Across town, USC Coach John McKay had his style.

Former USC coach John Robinson, a McKay assistant from 1972 to ‘74, said that the team was struggling against Oregon in 1972.

“It was a team we were supposed to kill,” Robinson said. “At halftime, John came in and fired the whole coaching staff.”

The coaches were all rehired before the second half and USC won, 18-0.

Prothro died in 1995, and McKay in 2001. But their large personalities dominated the UCLA-USC rivalry for six seasons, from 1965 to ’70.

McKay was already established at USC when Prothro, legendary briefcase in hand, came south from Oregon State 50 years ago.

The coaches were different yet equally driven. They clashed for six seasons, producing memorable games that resonated on the national level.

McKay’s way

McKay conjures up visions of a table at Julie’s, a restaurant bar near USC, where he would hold court with the media, spoon feeding them funny lines.

In the aftermath of a 51-0 loss to Notre Dame in 1966, he told reporters, “I told the team it doesn’t matter. There are 750 million people in China who don’t know this game was played. The next day, a guy called me from China and asked, ‘What happened, Coach?’ ”

That was McKay for public consumption. His players saw another side.

Dave Brown, a center at USC from 1968 to ‘72, said McKay called him into the coaches’ office one time and asked if he was growing a mustache.

“I told him I liked Robert Redford,” Brown said. “The next day, I wasn’t Robert Redford anymore.”

McKay watched practice from a tower and, at times, “it was the old, gray-haired guy coming down and screaming at some player. It scared the … out of you,” former USC guard Allan Graf said, laughing.

Graf, who was at USC from 1968 to ‘72, said, “He wanted to instill in us that we were the best.”

McKay spent nine seasons as an assistant at Oregon, from 1950 to ‘58, before joining a USC staff that had Al Davis as offensive line coach.

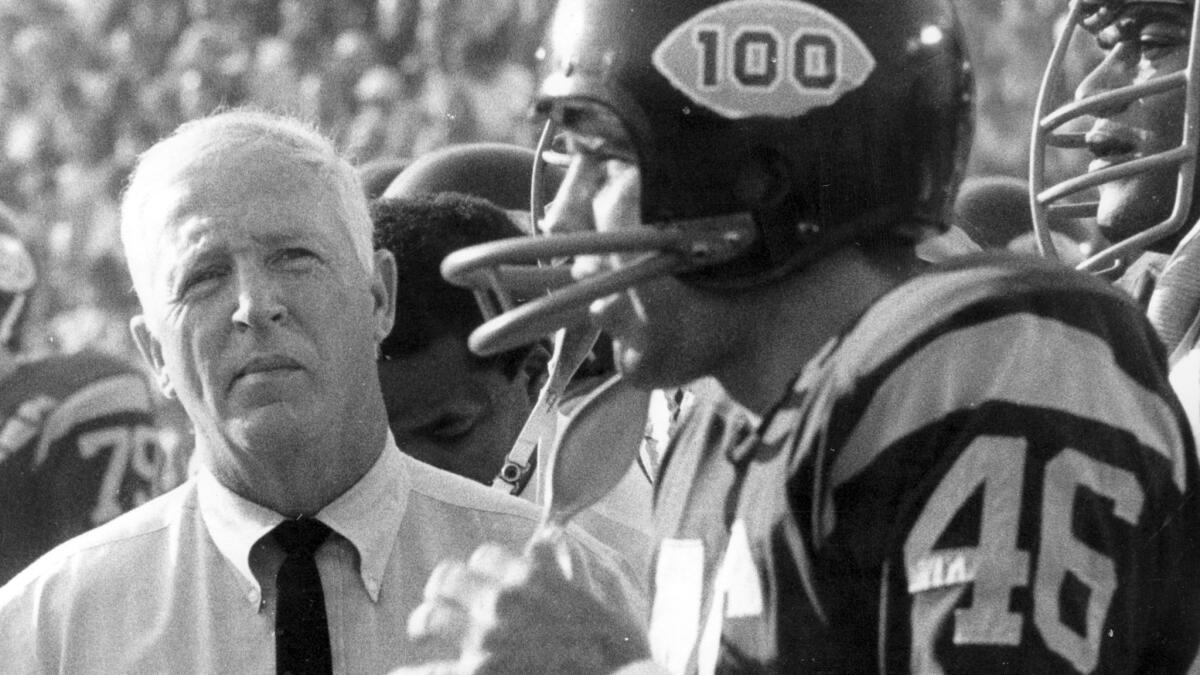

Trojans Coach John McKay talks with defensive back Gerry Shaw during game against UCLA on Nov. 23, 1969.

He was not a popular choice when hired as head coach in 1960, and there were rumors he was on his way out before the 1962 season. He then won the first of four national championships and that kind of chatter dissipated.

McKay, for all his wit, could be mundane in pre-game speeches.

Said Brown: “He would have a cigar in his mouth and would rub his chin and look down and say, ‘Charlie [Young], you’re starting at tight end. Pete [Adams], you’re strong tackle … go out and play football.’”

Post-game could be different.

After the 1972 Oregon game, Robinson said, “He told the team, ‘We are the second-worst team in America. Fortunately we played the worst team today.’”

McKay kept players at a distance.

“It was kind of a shock to the system the first time you saw him walking across campus,” said Mike Ryan, a USC guard from 1969 to ’72. “Rather than being your buddy and putting an arm around you, he put his head down and walked the other way.”

There was a reason.

“He didn’t want to be too friendly with anybody because he might have to demote them,” Graf said.

Still, talented players flocked to USC.

During his recruitment, Graf met McKay at Julie’s.

“He showed me his [1967] national championship ring and said, ‘You want one of those?’ ” Graf said. McKay added, “There’s only one place you can get one.”

Graf’s response was, “Where do I sign?”

Tommy Bruin

Former UCLA coach Terry Donahue, who played at UCLA from 1965-66, was part of a defensive front that included Dick Donald and Erwin Dutcher, which seemed to confuse Prothro.

“I’d see Tommy coming down the hall and I’d say, ‘Hey Coach,’ ” Donahue said. “He’d say, ‘Good afternoon Donald.’ There was only a one-in-three chance he’d call me Donahue. But screw up on the field and he never got your name wrong.”

Prothro had been an assistant at UCLA on the staff of Red Sanders, who made the Bruins into a national power, winning the national title in 1954.

When Prothro returned after his tour in Corvallis, the program was in a funk. He shook it up.

“Practice began at 3:12 p.m.,” said Beban, who won the Heisman Trophy in 1967. “Not at 3:15, not at 3:10. He was precise in everything.”

Strategy pulsed through Prothro’s veins, in football and other games. He was an exceptional bridge and chess player.

Wesley Grant, a UCLA defensive lineman from 1968 to ‘69, played with him often.

“He’d sit there smoking a cigarette and drinking a Pepsi and beat me,” Grant said. “I studied up, read every book on chess I could, thinking I could trap him. He would always trap me.”

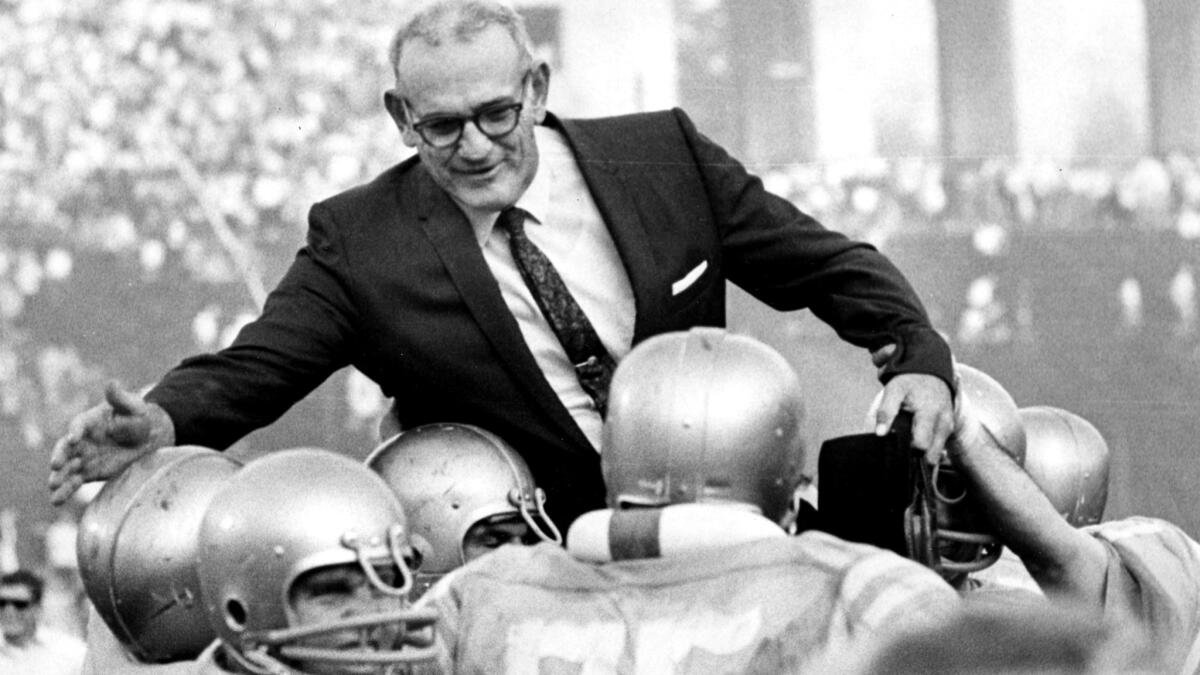

Coach Tommy Prothro is given a victory ride on the shoulders of his UCLA players after a victory over USC on Dec. 5, 1966.

Prothro opened up the offense and tossed in a bit of trickery. It led to a Rose Bowl appearance his first season and a victory over No. 1 Michigan State.

While sometimes aloof, Prothro did get involved with his players. Grant, who is African American, said that the chess games were filled with helpful conversation. Prothro, a southerner, encouraged Grant to stand up for himself.

“He told me a black man who didn’t do anything about certain situations wasn’t worth his salt,” Grant said.

Prothro, while not as glib as McKay, could be entertaining in defense of his players.

Danny Graham, a UCLA defensive back, was called for pass interference against Stanford in a 1969 game. On Monday, Prothro put a $100 bill on the table during a media session.

“He told them he was going to show the game film and anyone who saw me touch the receiver could have the $100,” Graham said.

That was part of Prothro’s quirky side the players loved.

Many people speculated about what the coach carried in the brief case that he carried constantly. Grant said that an assistant, who was once sent to fetch it, looked inside and found a list of the players who were starting, the game plan and a pack of cigarettes.

There were always surprises from Prothro. Beban was summoned to the front of the airplane after a game and worried he was in trouble.

“I sat down and he said, ‘Gary, I’ve been thinking. The United Kingdom’s parliamentary system is better than what we have,’ ” Beban said.

The games

The six-year tussle between the coaches has become folklore in the rivalry, and made a national impact.

In 1965, Heisman Trophy winner Mike Garrett ran wild for sixth-ranked USC. But Beban rallied the No.7 Bruins from a 16-6 deficit in the last four minutes.

The following year, USC was ranked seventh and UCLA eighth, but Beban sat out with an ankle injury. Norm Dow, a reserve quarterback who had played 62 minutes in three seasons, cobbled together a 14-7 victory.

“We were supposed to have the better players,” said Ron Yary, a USC tackle from 1965 to ’67. “They were always really prepared and played their hearts out.”

Both teams had one conference loss and the Bruins expected to go to the Rose Bowl. Conference officials voted the Trojans into the game. About 3,000 UCLA fans flooded the 405 Freeway in protest.

In 1967, Beban won the Heisman and UCLA was ranked No. 1. The Bruins led, 20-14, until O.J. Simpson took off on a 64-yard run that altered the series.

“They had six first-round NFL draft picks on that team,” Beban said. “We had a doctor, a rabbi and two lawyers.”

But it was the 1969 game that had a dramatic effect on Prothro.

UCLA, ranked sixth, led No. 5 USC, 12-7, with time running out. Graham was called for a questionable pass interference penalty on a fourth down play. On the next play, Jimmy Jones connected with Sam Dickerson in the back of the end zone for a 32-yard touchdown pass with 1:32 left.

“Losing in the 1969 game was harder on him than the O.J. run,” Graham said.

Recruiting “had gotten to him,” Beban said. On top of that, Grant said, “he was looking for new challenges.”

UCLA’s going-away present for Prothro was a 45-20 victory over USC in 1970. But it was Jim Plunkett’s Stanford team that went to the Rose Bowl.

Prothro jumped to the Los Angeles Rams. McKay followed him to the NFL after the 1976 season, taking over the expansion Tampa Bay Buccaneers. Both coaches are in the College Football Hall of Fame.

“They were very different,” Beban said. “I’d go to Tommy’s press conferences and he’d talk for 10-15 minutes before I realized he hadn’t said anything. McKay couldn’t go two sentences without telling a joke.”

But both were headed in the same direction.

Said Graham: “Back then, the Rose Bowl went through Los Angeles.”

[email protected]; Twitter: @cfosterlatimes

[email protected]; Twitter: @latimesklein

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.