Bryson DeChambeau’s powerful style didn’t work well in final round of U.S. Open

- Share via

SAN DIEGO — It was less than a year ago that Bryson DeChambeau tore up Winged Foot and won the U.S. Open with his drives launched into the stratosphere. There had been all sorts of hand-wringing and consternation about another round of Tiger-proofing of courses so they wouldn’t be overpowered by the next generation of huge hitters.

On Sunday, a course correction.

We watched DeChambeau come unglued on the back nine at Torrey Pines, tumbling from a share of the lead at the turn to a tie for 26th. He missed five of seven fairways on the back, and at times it looked like the guy notorious for his slow play couldn’t get off that course fast enough.

He had two bogeys and a double-bogey on holes 11-13, and melted down with a quadruple bogey on No. 17 that began with a drive out of bounds and cost him $200,000 in potential earnings.

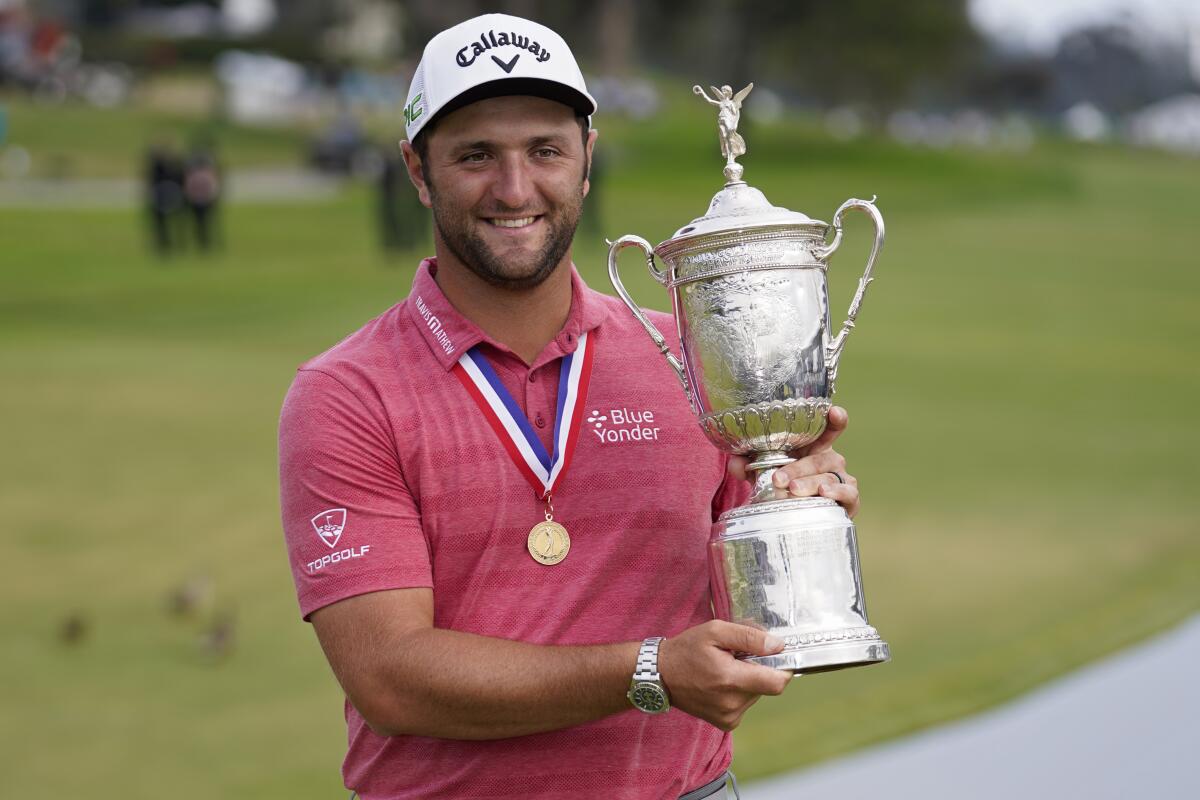

Jon Rahm won the U.S. Open on Sunday, shooting a final-round 67 at Torrey Pines Golf Course in San Diego to capture his first major championship.

Meanwhile, Jon Rahm grinded his way to victory with a steady diet of fairways and greens, which was far less adventuresome and made-for-TV entertaining but far more effective.

That’s the way the U.S. Open is supposed to be. More than any other major championship, it rewards players who can hit it straight, hit greens and stay out of trouble.

Last year, DeChambeau blew up that template. This time, the old template was relevant again.

That was the case with Louis Oosthuizen, too, who might have lifted the trophy had he been able to keep his drives in the fairway on Nos. 17 and 18. Instead, he was down in the ravine, and hacking his way out of the tall grass.

By DeChambeau’s thinking, what happened Sunday wasn’t a repudiation of his Bridgestone-blasting strategy, but simply the fickle winds of fortune.

“It’s just one of those things where I didn’t have the right breaks happen at the right time,” he said. “I could have easily gotten to seven-, eight-under today. I just wasn’t fully confident with the golf swing and just got a little unlucky in the rough and a couple other places.”

In fairness, he did have a share of the lead with eight holes to go, so maybe he’s right. But score one for the traditionalists, because what happened on the back nine at Torrey Pines underscored that there’s still a place for the controlled technicians — the Jordan Spieths of the world — who don’t try to win by blunt-force trauma.

Quick study

Rahm, the first Spaniard to win the U.S. Open, speaks English so well that his accent is hardly detectable. It’s hard to believe that he barely spoke a word of it when he arrived from Barrika, Spain, for his freshman year at Arizona State.

When he won a PGA Tour event for the first time — the 2017 Farmers Insurance Open at Torrey Pines, coincidentally — he said that memorizing rap songs really helped him with his English.

Particularly helpful to him, he said, were Kendrick Lamar’s “Swimming Pools,” and Eminem’s “Love the Way You Lie.”

“You can look them up,” Rahm told reporters. “They’re good.”

On the mend

It’s no surprise that four-time major champion Brooks Koepka was in the mix to win again Sunday. He always seems to be around the top when the stakes are highest, as he was last month at the PGA Championship when he tied for second behind Phil Mickelson.

The remarkable part is Koepka glided through a significant knee surgery with precious little turbulence.

Louis Oosthuizen missed a last-ditch chance to pry a U.S. Open victory away from Jon Rahm, leaving the South African majorly disappointed.

It was only a few months ago when Dr. Neal ElAttrache, team orthopedic surgeon for the Rams and Dodgers, operated on Koepka’s knee. ElAttrache repaired the ligament to restore stability to the golfer’s fractured kneecap, adding internal bracing and protection to allow accelerated rehabilitation and the chance to return to competition months ahead of a typical schedule.

ElAttrache was at Torrey Pines over the weekend both as a Koepka fan and to check on his knee, which the doctor said is healing at a remarkable rate.

“I talk to him almost every week, maybe once every three, four, five days, something like that,” said Koepka, who also works closely with physical therapists Heather Milligan and Marc Wahl.

“I think right after Augusta I spent some time out here with him and Heather. Everybody’s just — it’s a big team effort. A lot of hours put in and a lot of work just trying to make sure that everything is where it needs to be. I’ve got more mobility right now than I ever have, so that’s a solid thing where I can start building some strength again and keep building that up and just keep the progress going.”

Local flavor

Among the more revered fixtures at the U.S. Open is Bob Ford, who announces the names and hometowns of players on the first tee. He was the longtime head PGA professional at both Oakmont, which has played host to nine U.S. Opens, and Seminole in Juno Beach, Fla.

Ford, 67, retired from Oakmont in 2016 after 37 years, and stepped down from Seminole this month. He split time for 16 years as pro at both clubs. He was inducted into the PGA of America Hall of Fame in 2005, and four years ago won the Bob Jones Award, the highest honor the USGA bestows.

But for him, working as the U.S. Open starter is particularly special.

With a gliderport next to golf course, paragliders can spend hours hovering at U.S. Open. “The gliders are part of the landscape,” says Rory McIlroy.

“I love it,” Ford said. “It’s fun to be inside the ropes just doing anything. To have control of the mic and the interaction with the players, it’s a blast.”

Like many in his shoes, Ford occasionally struggles with some pronunciations. One that has given starters troubles is the “can-YADA” part of La Ca

ñadaFlintridge, hometown of Collin Morikawa.

“I screwed it up and said La Canada,” Ford said, pronouncing Cañada as in our neighbor to the north. “Kay Cockerill who was doing announcing for NBC came over and I said, ‘How do you pronounce this?’ She said, ‘La can-YADA.’ But then I get up there and I’m reading the script and I read it wrong.

“So on Saturday, I see Collin and I said, ‘I know how to say La Cañada. I just choked.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry about it. A lot of guys have gotten it a lot worse than you.’ ”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.