Column: For this soccer mom, joining the club was a decade well-spent

When you have a child in Southern California, you are all but legally required to enroll him or her in AYSO soccer. I don’t know how it happens. One minute you’re playing her Baby Mozart and pretending that the ability to memorize “Brown Bear, Brown Bear” is the same as reading, and she’s only 3 so it must mean she’s a genius, and the next, you’re telling her not to worry about the 5-year-old she just knocked to the ground while dribbling because she should “SHOOT!”

It’s all great fun, cutting up orange slices and making up snack bags, and if that child is a her, there’s the added benefit of learning how to create those beribboned hair elastics that some super-crafty mom managed to make part of the official team uniform.

If that child shows any real talent, as my eldest daughter did more than 10 years ago, you will then find yourself confronted with the question of whether to “go club.” Club soccer teams are more competitive, more demanding and more expensive. They are part of a system that includes tournaments, showcases, camps, and teams of graduated skill and visibility that can lead to college scholarships, positions on national teams and, upon rare occasion, the Olympics.

This isn’t just true for soccer; there are competitive club teams for many sports — basketball, baseball, softball, swimming, water polo, volleyball. Although my husband and I didn’t know this at the time, many people have very deep and conflicting feelings about club sports. And perhaps because of the popularity of AYSO, people have very specific and particular feelings about girls club soccer.

I have done many things for which mothers are often criticized. I worked outside the home; breastfed my children in public; enrolled them in group daycare; took them to PG-13 movies long before they were 13; and let them watch television, including cable, whenever they wanted as long as the homework was done.

Maybe I was just too busy to notice, but I never felt judged as a parent — until I put my daughter on a club soccer team.

At best, it was an eye-rolling comment from a non-club parent about how “well, we’re just not willing to give up our entire weekends.” At worst, it was a doorstep lecture on how “ridiculous” it was that so many kids were “pressured” into playing on these advanced teams, how it was ruining sports and childhood and perpetuating the elitism of “super-parenting.”

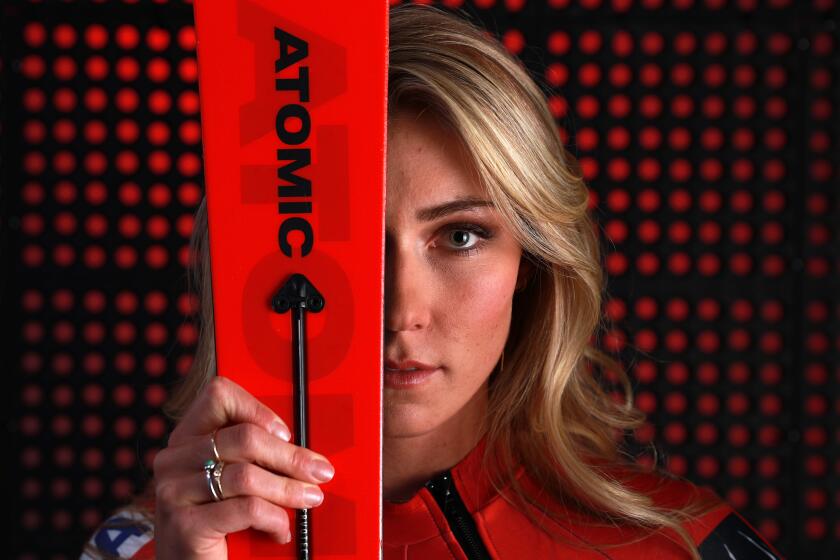

Game Changers: Trailblazers

The Times’ profile series of women who are pioneers in sports.

If the lecturer in question (who was, you guessed it, a dad) had ever met my daughter Fiona, he would have known that it was, and remains, physically, psychologically and emotionally impossible to pressure her into doing anything. And while it is certainly true that being able to afford club fees and travel expenses is a privilege, the notion that my husband and I were ever trying to do anything but survive parenting is laughable.

As for ruining sports, well, it’s kind of hard to argue that any competitive girls’ sports program could ruin anything but the all-male standard of athleticism since, you know, competitive girls’ sports programs pretty much didn’t exist until a generation or two ago.

Nearly 50 years after Congress passed Title IX, female athletes are still scrambling for a fair shot in the male-dominated world of sport. In hockey, top Americans and Canadians train with their national teams part-time; the rest of the season, they have only a small pro league that offers twice-a-week practices, weekend games and thin salaries.

Even among those who supported our decision, the overall assumption was that Fiona was playing club so she would get a college scholarship. So when she decided, in the beginning of her senior year in high school, that she didn’t want to play Division I soccer in college, many friends expressed sympathy, as if all that time and money had been for naught.

Except it wasn’t.

We live in a country where sports remains our number one metaphor, a national short-hand for unity, hard work, sacrifice and gutsiness. A short-hand from which, until recently, most girls and women have been excluded.

So why is the notion of playing on a competitive sports team considered a waste if it doesn’t result in a scholarship? (Strangely, no similar comments had been made when my son joined a club basketball team with no plans to play in college.)

I admit that when coaches began commenting on Fiona’s wicked left foot, my husband and I entertained “full-ride” daydreams. And during the first dozen of approximately 578 trips along freeways leading to San Bernardino, Irvine, Pleasanton, San Diego and (shudder) Las Vegas, we certainly wondered if this was really worth the time, effort and sunscreen.

But if you need to know the location of any Starbucks or Panera in the state of California, I can probably tell you, and believe me, that comes in very handy.

Game Changers: NextGen

The Times’ profile series of women in sports who continue the fight for equality.

More important, one of the main reasons Fiona was clear-eyed enough to know that she wasn’t willing to make the commitment required by collegiate soccer, and confident enough to say so, was because she played club soccer.

From the moment we informed her that she was in charge of keeping her schedule, getting her homework and studying done before practice and making sure that she had whatever she needed in her bag before we got into the car, club soccer helped her become a responsible young adult.

For 10 years, she showed up at practices two nights a week and games almost every weekend. For 10 years, she went to spring and summer camps to improve her footwork, her strength, and her speed. She moved from team to team, meeting all sorts of girls whom she would have never met otherwise. Some became friends, some did not, but she figured out a way to work with all of them. She had coaches she liked and coaches she did not like; she got hurt, praised and yelled at. She was put in high-pressure situations and occasionally benched. She learned that you can’t control the refs, that being late or skipping practice had consequences, that she couldn’t go to sleepovers, or later, parties, when she had a game the next day, that she had to respect her body if she expected it to perform.

Sure, I spent innumerable hours frying on sidelines and fretting about hydration, living out of a car that was perpetually littered with water bottles, granola bars and the constant rattle of sunscreen cans. But my kid can change out of a soccer uniform and into party clothes in a moving car with her seat belt on in less than five minutes, and the value of this skill cannot be overstated.

The Times asked a sample of players, coaches and administrators to discuss the pressing issues of the day.

I still remember sitting in the chilly dark of a Vegas tournament, watching her take the field for the first time with a team she had just joined, a team on which all the girls were several years older and more experienced. The soccer field seemed enormous, and all the girls far bigger than my daughter. I was a nervous wreck. She just played her game. It still seems wildly heroic to me.

Soccer also gave Fiona a respite from all the drama of middle and high school. She had something else to do besides fret about grades and friends, endless testing and crushes. It was something she was good at, even when she was playing against boys — something, she has said, that could take her out of her head and the angst of adolescence.

And surely we all understand by now that participation in sports is associated with physical benefits like lower blood pressure and better fitness, emotional benefits like improved self-esteem and academic benefits like higher rates of college attendance and retention.

Also, if you need someone to cross a very crowded distance in the least amount of time to, say, stop a runaway toddler or get to the front of a ticket line, your best bet will always be a soccer girl.

The streaming video revolution that is upending the long-entrenched habits of TV viewers is creating more opportunities for women’s sports to get wider exposure.

Fiona and I had plenty of uncomfortable moments during our life on the road, and I certainly made my fair share of “I hope you appreciate this” and “I did not drive all this way to watch you just stand there” kind of comments. But we also sang and laughed and talked, a lot. (Seriously, if you want your teenager to talk to you, put her in the car and get on the 5, north or south, for three hours.)

And while I did weary of answering “oh you’re so tan; did you go to Hawaii?” with “no, I went to Irvine,” I never got tired of watching my daughter do something she could do so well, something I never in a million years could do myself.

Win or lose, scholarship or no, club soccer gave Fiona an opportunity to be something that, when I was her age, only a few of the most driven and extraordinary girls and women could be: An athlete.

And that was worth all the time and money and sunscreen in the world.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.