For Myles Garrett and Mason Rudolph, where does football end and the law begin?

- Share via

If Myles Garrett had walked down the street, grabbed a five-pound brick — about the same weight as an NFL helmet — and bashed someone over the head, the police would have arrested him.

But the laws that apply to normal life don’t always translate to sports.

It remains unclear if the Cleveland Browns defensive end will be charged for Thursday night’s brawl that saw him rip the helmet off Pittsburgh Steelers quarterback Mason Rudolph and turn it into a weapon, clobbering Rudolph.

Though the NFL took swift action Friday, suspending Garrett without pay for the rest of the season and perhaps longer, Cleveland police announced they will not investigate the matter unless Rudolph files a complaint. The quarterback does not wish to pursue legal action, according to a person close to him who did not wish to be identified.

Regardless, the incident has taken its place in a history of sports violence that includes boxer Mike Tyson biting off the tip of Evander Holyfield’s ear and San Francisco Giants pitcher Juan Marichal attacking Dodgers catcher Johnny Roseboro with a bat.

Some of these assaults were prosecuted; others weren’t. At issue is the notion that athletes consent to a certain amount of physical contact every time they step onto the field of play.

“We always have this big carve-out for sports,” said Stan Goldman, a Loyola Law School professor. “People are horribly injured in boxing and football but we kind of allow it because, the theory is, it’s socially acceptable.”

Thursday’s incident began with Garrett tackling Rudolph in the final seconds of a 21-7 victory for the Browns. The quarterback took exception and initiated the sort of pushing and shoving common to such plays, but also grabbed and pulled Garrett’s helmet.

Things quickly escalated when two Steelers linemen got involved and Garrett tore Rudolph’s helmet off, taking a windmill swing with it that struck Rudolph in the head. The scuffle continued with players tumbling to the ground and one of the Steelers, Maurkice Pouncey, kicking Garrett.

Cleveland Browns’ Myles Garrett was suspended indefinitely without pay for hitting Pittsburgh Steelers’ Mason Ruldolph in the head with a helmet.

“I made a terrible mistake,” Garrett said in a statement Friday. “I lost my cool and what I did was selfish and unacceptable.”

While issuing lesser penalties for two other players, the NFL hit Garrett with the long suspension and a $250,000 fine for violating “unnecessary roughness and unsportsmanlike conduct rules, as well as fighting, removing the helmet of an opponent and using the helmet as a weapon.”

“It was bush league, it was a total coward move on his part,” Rudolph said, adding: “I’m not going to take it from a bully.”

From a legal standpoint, the law in Ohio — where the game was played — states that no person “shall knowingly cause or attempt to cause physical harm to another,” which might seem like exactly what Garrett did.

The case becomes less clear, Goldman says, because of what society expects from sports.

Fighting, in particular, has long been considered a part of football and hockey. Prosecutors might take this into consideration when thinking about their chances of persuading a jury.

There is also the question of punishment for someone who gets into a football brawl as opposed to, say, a barroom fight.

Cleveland Browns’ Myles Garrett ripped the helmet off Pittsburgh’s Mason Rudolph and used it to strike the Steelers quarterback in the head.

“Do you lock him away in prison?” Goldman asked.

Authorities have often looked the other way when it comes to violent outbursts in sport.

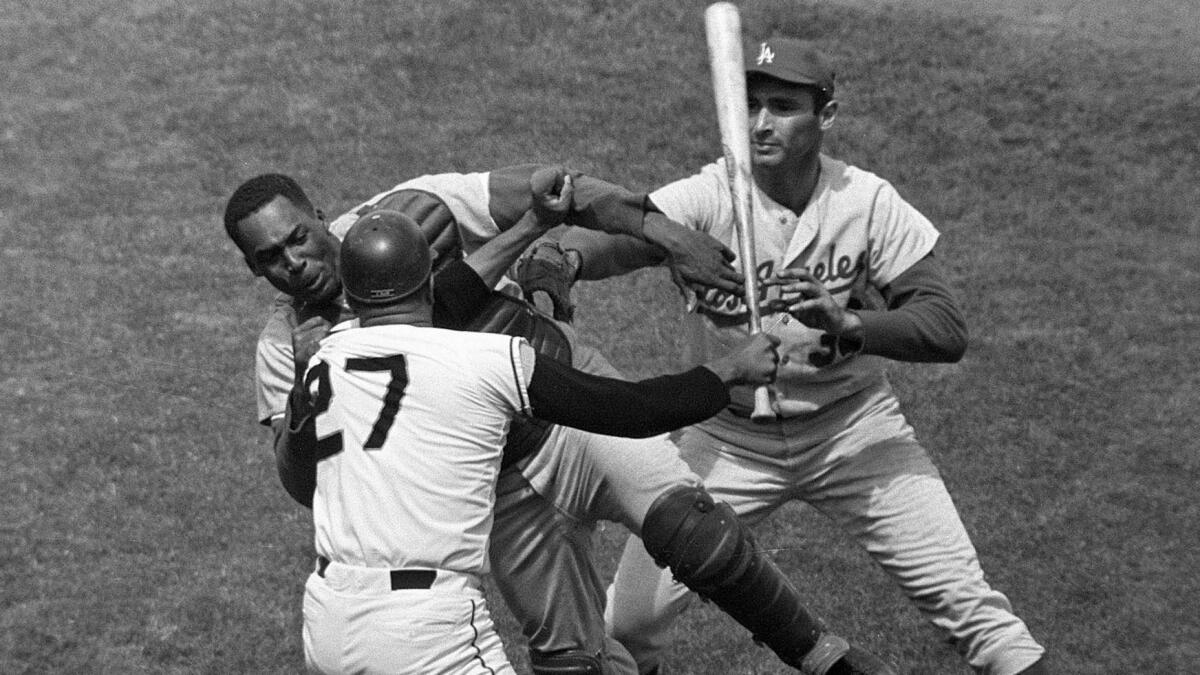

In the summer of 1965, as the Dodgers played the Giants in their heated rivalry, Marichal came to bat and got into a confrontation with Roseboro. Marichal swung at the catcher, leaving Roseboro with a bloody, two-inch gash to the head.

When asked about the penalty Marichal should receive, Roseboro told reporters: “He and I alone in a locked room, for about 10 minutes.”

The catcher ultimately filed a civil lawsuit that was settled for $7,500. There were no criminal charges.

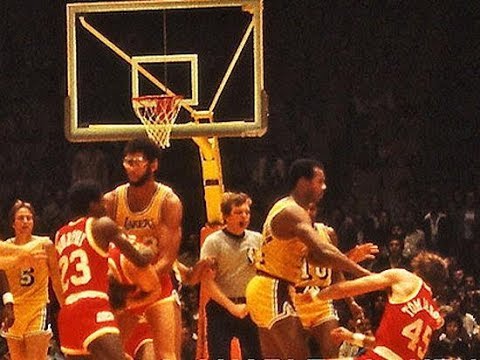

Lakers forward Kermit Washington was never arrested for the 1977 sucker punch that left Rudy Tomjanovich, then of the Houston Rockets, with a fractured skull and broken jaw.

Two decades later, Tyson was still on parole for a previous rape conviction when he fought Holyfield, leaning close and using his teeth to rip away. Las Vegas authorities declined to arrest him.

“There are certain agreements both fighters enter into,” Mary Kay Moore, an official with the Cook County State’s Attorney, told the Chicago Tribune. “If he was convicted of biting someone outside the ring, he would serve the rest of his sentence before serving the new sentence.”

But prosecutors haven’t always hesitated to intervene.

When hockey player Marty McSorley smashed an opponent’s head with his stick in 2000, Canadian authorities brought assault charges and ultimately sentenced him to 18 months’ probation.

A fight that broke out between the Detroit Pistons and Indiana Pacers, which quickly spilled into the stands, resulted in charges against five players.

You’re weighing out the government resources and deciding whether you’re going to prosecute,” UCLA law professor Peter Johnson said. “There are times when the prosecutor says there needs to be some criminal conviction.”

It was less than two weeks ago that the Browns waived safety Jermaine Whitehead for posting threatening, profanity-laced comments on Twitter.

Though Garrett has referred to himself as a pacifist and a poet, the Browns’ defensive lineman was previously fined more than $50,000 this season for fighting and late hits. After he struck Rudolph on Thursday night, the quarterback’s agent took to social media.

“There are many risks an NFL QB assumes with every snap taken on the field,” Timothy Younger wrote. “Being hit on your uncovered head by a helmet being swung by a [defensive end] is not one of them.”

There is a general theory in law that no one can consent to great bodily injury, not even professional athletes, Goldman said. So stepping on a football field does not absolve all wrongdoing.

That question is, where to draw the line?

Prosecutors, who could pursue an investigation without Rudolph’s involvement, might face another issue. Would potential jurors in Cleveland hesitate to convict the home team’s star player and a former No. 1 draft pick?

“It’s tricky,” Goldman said. “It wouldn’t be as tricky if football weren’t the No. 1 spectator sport.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.