How life (and death) change Egyptian soccer and its American coach

- Share via

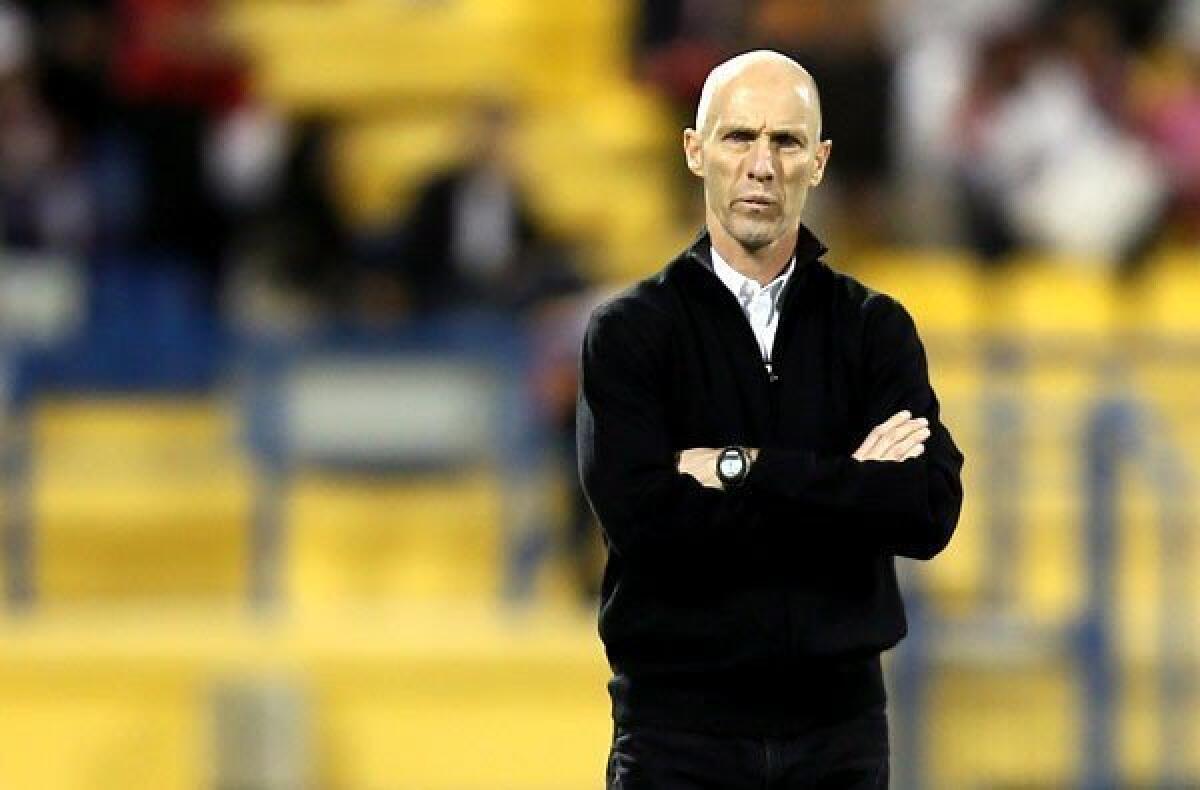

Bob Bradley wasn’t looking for an adventure as much as he was looking for a job after being fired as coach of the U.S. soccer team two years ago.

But in Egypt he found both. When Bradley arrived in the fall of 2011 to take over Egypt’s national soccer program, the country was teetering between revolution and rebellion.

The Arab Spring uprising had already unseated longtime leader Hosni Mubarak, and five months after Bradley began work a deadly riot broke out at an Egyptian Premier League match, killing 74.

It probably wasn’t the best time to take any soccer job in Egypt. Because of the violence the country’s top domestic league was shut down twice, leaving the players without pay or a place to play. And when the government declined to provide adequate security, Bradley’s team had to play its first World Cup qualifier in an empty military stadium.

Yet despite it all — or maybe because of it all — Bradley has Egypt a win away from the final round of qualifying for next summer’s World Cup, a tournament it has played in just twice since 1930.

“In those difficult circumstances we were able to start to establish something, a trust and an understanding of the opportunity that we had to try to do something special during a time in the country when, honestly, everything’s pretty difficult,” Bradley says.

“When a national team steps on a field you need to make sure that people look on that field and feel proud. They feel like they’re part of it. I think that certainly fits the situation and the challenges that we see here.”

As astonishing as soccer’s survival in Egypt may seem, however, the bigger surprise is that Bradley has become its savior. He was criticized as robotic, unimaginative, even dispassionate while leading the U.S. into the knockout round of the 2010 World Cup. Now, many in Egypt insist Bradley saved their team through his creativity, emotion and force of will.

The day after the February 2012, riots in the Suez Canal city of Port Said — an event Bradley called “a massacre” — the coach and his wife, Lindsay, marched with thousands of Egyptians in Cairo’s Sphinx Square to honor the dead. They visited a memorial, where they spoke with relatives of those who had died. Quietly, they donated money to the survivors. Bradley, his wife and two daughters, also rallied support for the Children’s Cancer Hospital of Egypt, to which they also gave money. And last November, after an accident involving a train and school bus killed dozens of children in Asyut, 230 miles south of Cairo, Bradley met with the victims’ families.

“Egypt is a region where emotion counts. People respond emotionally and that response is important,” says James M. Dorsey, a former foreign correspondent for the New York Times and Wall Street Journal, who writes a blog on Middle Eastern soccer. “If you respond to situations with a sense that you understand what’s going on and that you empathize and that you’re part of this, people value that.”

Hassan El Mestikawy, a well-known sports analyst in Egypt, pays Bradley an ever bigger compliment. “He’s an Egyptian,” El Mestikawy says.

Bradley had managed three Major League Soccer teams, including Chivas USA, and some age-group U.S. national squads before being chosen over Juergen Klinsmann to manage the U.S. team in 2006 — only to be replaced by Klinsmann five years later, something Bradley still won’t talk about.

Europe, not the Middle East, was Bradley’s first choice for a new job. After interviewing unsuccessfully with a club team in Mexico, then reportedly being considered for jobs at Fulham and Aston Villa in the English Premier League, Bradley began to warm to Egypt. Zak Abdel, his goalkeeper coach at Chivas and now an assistant with the Egyptian national team, told him about the country’s fervor for soccer.

Many worried that Bradley’s stoicism would be a poor match for that passion.

“I’d heard those stories. That he was very distant, aloof and not loved the way he is in Egypt,” says Dorsey who, having spent much of his life as a war correspondent, has a theory why Bradley has done well.

“One of the things you learn in war situations is nothing is more adaptable than a human being,” he says. “Your concepts of what is normal shift. So if you were in a situation of stress, that situation becomes your normal. And that brings out different qualities.”

For Bradley, 55, the shift took place after the deadly melee in Port Said, where fans stormed the field after a Premier League match between the home team, Al-Masry, and Al-Ahly from Cairo. Many in Egypt believe the attack on Al-Ahly players and their main supporter group, the Ultras Ahlawy, was orchestrated by the police and military in retaliation for Ultra-led protests that helped bring down the Mubarak regime.

The riot became personal for Bradley, because many on his national team had played in the game and were caught in the violence that followed. “They experienced things that will live with them for the rest of their lives,” Bradley says. “There were fans that used the locker room as the first aid area. There were young fans that died in the locker room.”

No player was affected more than midfielder Mohamed Aboutrika, one of Egypt’s most decorated stars but one who, at 34, Bradley had been urged to leave off his roster.

“The first time I met Aboutrika in the midst of all the difficulty and the emotion it was so clear how much it meant to him to have one more chance to go to the World Cup,” Bradley said of the player, who watched a 14-year-old boy die in his arms on the floor of the Al-Ahly dressing room. “With everything he had done in his career there was still this one thing that hadn’t been accomplished. And from that moment on, I felt strongly that this was going to be an important thing for this group, to have an experienced player who was so committed.”

Six weeks ago, in Egypt’s most recent World Cup qualifier, Aboutrika rewarded his coach’s confidence by scoring on a penalty kick in the 88th minute to beat Zimbabwe, 2-1. Egypt is undefeated halfway through the second round of the regional qualifying tournament.

The revolution created more than just emotional challenges for Bradley and his team, which is made up mostly of domestic players little known outside Egypt. When the Premier League halted play, Bradley had to scramble to find ways to keep his players fit and fed.

First, he organized additional training camps. Then, with the government unwilling to guarantee safety in Egypt, Bradley took his team on a barnstorming tour of the Middle East, playing 12 friendlies in five countries.

But the team wasn’t forgotten at home, where its matches were broadcast on as many as 12 channels. Through it all, the players grew close.

“In any national team you try to establish what it means to be on that team. What an honor it is,” Bradley says. “Everybody in Egypt has this dream for the team to go to the World Cup. Right now we have a real responsibility and we have a chance to do something that everybody would think is very special. And we can’t let the things that are going on on the outside take us away from this idea.”

The situation got surreal when FIFA, the world governing body for soccer, ordered Egypt home for its first World Cup qualifier last June. With security a concern, Bradley’s first competitive match as national coach was moved from Cairo to Alexandria, on the Mediterranean coast, where it was played behind locked gates in a military stadium.

There, a military band played the national anthem as the players, standing ramrod straight, sang the lyrics. Then Egypt kicked off against Mozambique before 86,000 empty seats.

“It’s difficult to play matches in empty stadiums,” says Bradley, whose team won, 2-0. “It’s a very strange feeling. It’s so quiet. A game without fans has no soul. Playing in front of fans that care, fans that have an incredible passion for the team, this is what drives our game.”

And it’s a mix of compassion, courage and steely resolve that drives Bradley, a New Jersey native who has achieved star status, and is mobbed by Egyptians when he goes out in public. He has learned to speak broken Arabic — beginning with Kas al-aalam, the term for World Cup.

Everyday life remains a challenge in Egypt. Drivers wait up to four hours in gas lines, the economy is in free fall and even basic foodstuffs are in short supply. The changes also involve Egypt’s soccer federation: The men who hired Bradley have all resigned.

Still, Egyptians find hope in their soccer team’s success.

“More than anything else I get asked why am I still here? That with everything going on in the country why would you stay?” says Bradley, whose team has a 16-6-4 record since coming to Egypt. “It’s a lot of things that you can’t control. But … we can control what we’re about. We can control that, in the midst of everything, we’re not going to let any of it get in our way.

“So the answer as to why I’m still here is because if I’m trying every day to make sure that the players keep their eye on the prize and stay committed to this whole thing, my word wouldn’t be worth much if I was looking for a way out.”

It’s taken almost a year, but a sense of normality has begun to return to the Egyptian team, which will play an exhibition in Cairo — in front of fans — on June 4, before resuming World Cup qualifying five days later in Zimbabwe.

If Egypt beats Zimbabwe, combined with a loss by Guinea, the Egyptians will win the title in their four-team group and move on to next fall’s regional finals, a two-leg series, with an invitation to the 2014 World Cup in Brazil on the line.

Egypt last played in the World Cup in 1990. Four years ago it came within a goal of qualifying, losing a decisive playoff to Algeria, 1-0. Then came the revolution and the riots — obstacles Bradley and his players have endured, leaving Egyptians optimistic the team will reach the World Cup for the first time in a generation.

“They have a chance,” El Mestikawy, the Egyptian commentator, agrees. “It is important what he’s doing now. It he succeeds and goes to the World Cup final, it would be very large thing for the Egyptians. Maybe they’ll look again to football as a national game.

“So I think we need to go to the World Cup. We need Bob Bradley’s success.”

twitter.com/kbaxter11