Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Nick Theslof’s grandmother taught him to ice skate at about the time he was learning to walk, which really didn’t prove to be much of a life skill since Theslof went on to play professional soccer, not hockey.

But there was another lesson Theslof learned from his grandmother simply by being near her. And it has proved infinitely more valuable.

“She was my example,” said Theslof, a Galaxy assistant coach. “She was inspiring just by watching her move and talk because she was a little different. You don’t quite understand it, but you want to be to that level.

“That’s something I realized very young. I wanted to try to achieve and be good like my grandmother.”

We should all strive to achieve and be good like Vivi-Anne Hulten, an Olympic medalist and 10-time national champion figure skater in the 1920s and ‘30s who was once hailed as Sweden’s greatest female athlete. However, Theslof remembers his grandmother not for her medals, which he keeps on display in his Lakewood home, but for a simple act of profound courage and character that came to define her.

It has been 60 years since the entire U.S figure skating team died in a plane crash in Belgium. For those who knew the skaters best, the loss remains vivid.

As Hulten approached the medal podium after finishing third in the 1936 Winter Games, she was told she would have to perform a Nazi salute to honor German chancellor Adolf Hitler. She refused.

“At the time, for a female to stand up for herself in that environment in Germany, the amount of integrity and bravery that it took from her, it’s hard for me to explain,” Theslof said. “She had a way to achieve in that moment. It wasn’t about the skating. It was about her integrity.”

Hulten, who left Sweden for the U.S. and taught skating in the Carolinas, Tennessee and Minnesota, eventually followed her family to Southern California where she died in 2003 at the age of 91. By then Nick’s playing days had been ended by a severe Achilles injury and he was on the second stop of a coaching career that would take him to eight teams in four countries, a career in which he’d coach in a World Cup with Germany and win an MLS title in Toronto.

He could win another MLS Cup this fall with the Galaxy, who Saturday moved a big step closer to clinching their first Western Conference title in 13 years. But like his grandmother, Theslof won’t allow his career to be defined by shiny prizes that will lose their polish over time.

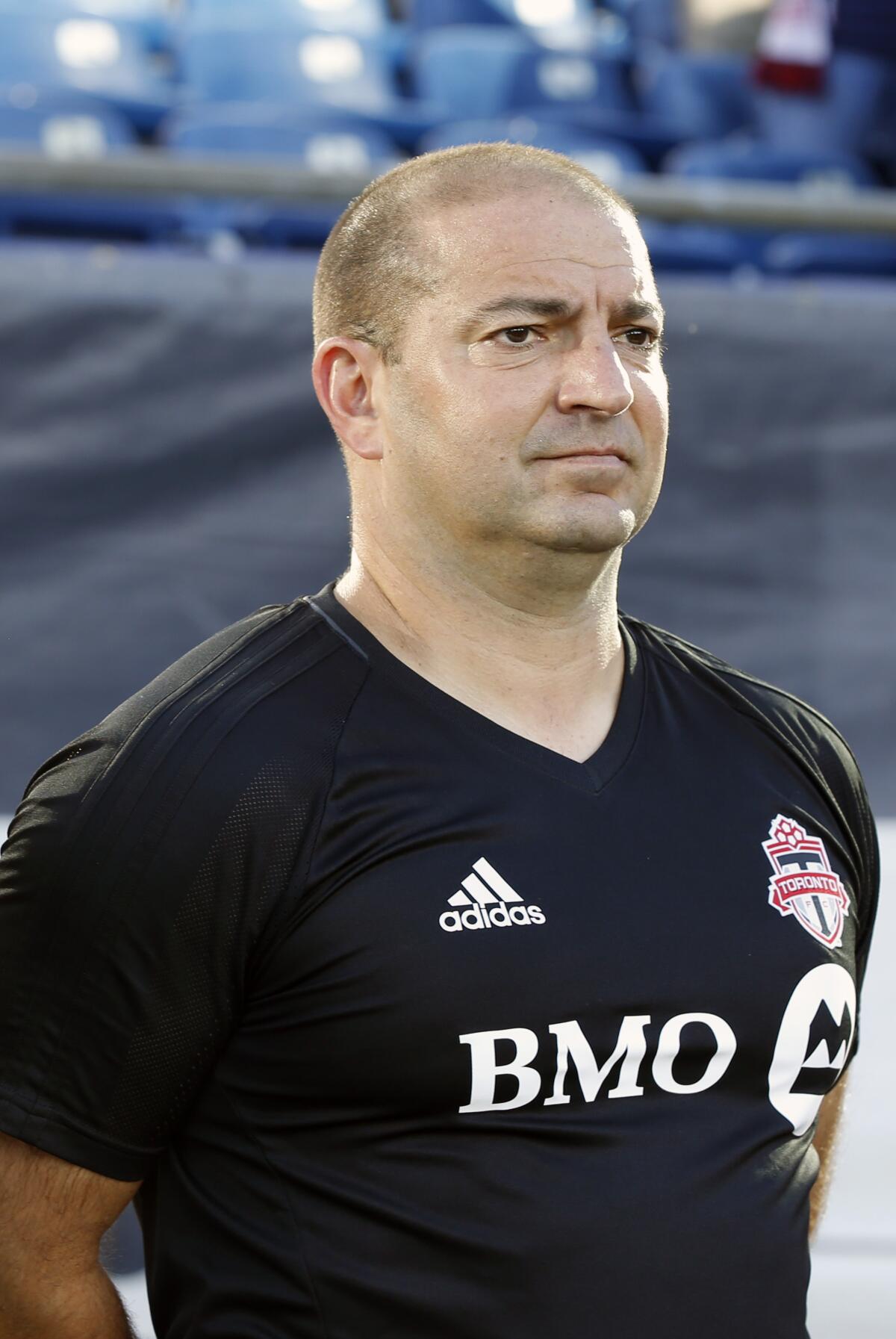

“What’s important for me is that everyone in this building knows who I am and they trust me, they know that I can help them,” said Theslof, 48, who won a national title at UCLA and played in the youth program of Dutch giant PSV Eindhoven, yet remains among the most unsung members of a coaching staff that includes three MLS all-stars and three national team players.

“My name isn’t synonymous with the things that my colleagues have done,” he said. “I’m really happy for them. But I’m also happy that I’m different.”

In this case different doesn’t mean inferior. And Theslof’s colleagues are well aware of what he brings to the job.

“Nick’s superpower, his ability to understand how the individual player works with the ball, is spectacular,” Galaxy coach Greg Vanney said of his former UCLA teammate. “Nick does a lot of managing and watching players, how they’re moving, and how they’re moving with the ball, in order to create more technical efficiencies or improvements. He’s one of the best I’ve ever been around.”

That’s also something Theslof said he learned from his grandmother, who was 64 when he was born.

“Growing up, when I watched my grandma teaching ice skating and teaching humans how to perform, I was always so taken aback by how she looked at the body and balance and the little technical things that allowed people to perform better that a normal person would maybe not see,” he said, sitting under an umbrella on the concourse at Dignity Health Sports Park last week after a morning training session. “She would take time and really slow things down and make sure that the human was moving correctly. I found that fascinating.”

Theslof grew up playing hockey in Minnesota where his grandmother, who had toured with the Ice Capades, ran a skating school whose clients included Herb Brooks’ gold-medal winning U.S. hockey team.

Former Olympic figure skater Todd Sand nearly died after suffering a heart attack. His wife and skating partner says he is making progress in his recovery.

“One afternoon she came over to our house and Brooks was with her,” Theslof recalled. “And we go to a hockey store and buy a stick. I’ve had a very unique life and some very unique experiences.”

Although Theslof’s grandmother had statues erected in her honor in Hungary and at the World Figure Skating Museum and Hall of Fame in Colorado and performed for the king and queen of Sweden when she was 80, she’s probably best remembered for her snub of Hitler and her spat with legendary Norwegian skater Sonja Henie.

After being ordered to salute the German dictator, Hulten told interviewers decades later, she responded by saying, ”I’m Swedish; I don’t do that.”

“I just stared at him,” she said. “He was a scary person.”

The long-running feud with Henie, a three-time gold medalist and 10-time world champion, was much more personal and vicious, with both sides trading barbed insults. And although the rivalry came to define skating for a generation, Theslof said his grandmother had the last laugh.

“Sonja Henie used to date my grandfather,” he said of Gene Theslof, who was Henie’s skating partner before he left her to marry Hulten.

The Galaxy beat Austin FC 2-1 on fan appreciation night in Carson and are on the cusp of winning their first Western Conference crown in 13 years.

Although Hulten helped steer Nick Theslof onto the ice as a boy, he quickly transitioned to soccer and by age 15 he was in the Netherlands playing at Eindhoven. He returned to the U.S. to win an NCAA championship at UCLA under Sigi Schmid before injuries forced him into coaching.

“People were saying, ‘Well, you’ve got a good eye for coaching,’” Theslof said. “I knew my grandma was coaching a lot. For me, coaching was second-best to playing. I feel like I had grown up with kind of a coaching, teaching, performance side to me.”

In his first job, as an assistant at Ohio Wesleyan, he won an NCAA Division III title and he later worked under Jurgen Klinnsman with the German national team and Bayern Munich, then at Chivas USA.

In 2014 he joined Vanney’s staff at Toronto FC, and the two have been together ever since.

“There’s a little bit of a grind in coaching, then you come out the other side in the performance and it feels good,” he said. “I’m proud of not only the successes that the teams I’ve been with have had, but I’m also very proud of the players that I’ve built relationships with.”

⚽ You have read the latest installment of On Soccer with Kevin Baxter. The weekly column takes you behind the scenes and shines a spotlight on unique stories. Listen to Baxter on this week’s episode of the “Corner of the Galaxy” podcast.

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.