Grant Fisher could help U.S. end its distance race drought at Paris Games

When Grant Fisher stepped to the starting line for the 10,000-meter final at the Tokyo Olympics, he knew he had to cover a lot more than 10 kilometers to get to the front of the field.

“I remember lining up next to Joshua Cheptegei and he had just broken the world records in the 5K and the 10K,” Fisher said. “He just run 26:11. I had just run 27:11.

“And I was like, ‘Man, how am I even going to get close to this guy?’”

A little more than two months before the start of the Paris Olympics, that gap has closed considerably. Fisher has run 26:33.84 and has the best time in the world at 10,000 meters since Cheptegai, a Ugandan, set his record in 2020. That makes Fisher one of the favorites to strike gold in this summer’s Games, something no U.S. distance runner has done in four decades.

“When I was growing up, the narrative was you can’t run with the East Africans,” said Fisher, 27. “I’ve been close. Some work to be done, of course. And yeah, people are closing it down.”

Joan Benoit, who won the women’s marathon in 1984, was the last American to climb to the top of the medal podium in a race longer than 1,500 meters. Frank Shorter was the last U.S. male to do that, winning the marathon in 1972. No American has won a distance race on the track since 1964, when Billy Mills upset a loaded field to win the 10,000.

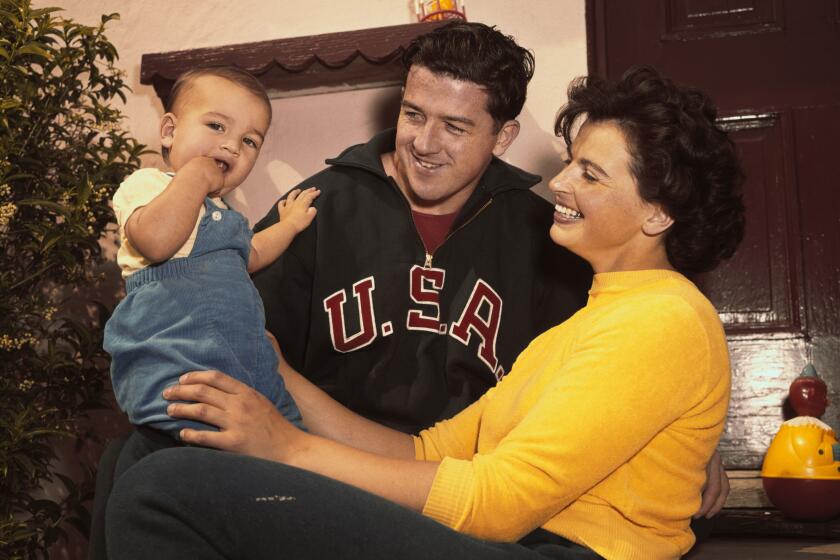

Olga Fikotova Connolly, who recently died at age 91, was an Olympic champion at the center of a East vs. West controversy at the 1956 Olympics.

“I like that we’re even having this conversion,” said Mike Scannell, Fisher’s coach. “That means maybe we are entering the stage where we’re in the conversation for a podium slot in Paris. My initial read on that is yes, things are going extremely well for not just Grant, but for all Americans.”

The long road to this spot began in 2001, when former UCLA coach Bob Larsen and Joe Vigil, who coached distance runners for the U.S. Olympic team, began training their athletes in the 7,900-foot altitude of Mammoth Lakes. Three years later Meb Keflezighi and Deena Kastor became the first American distance runners to step on an Olympic medal stand in 20 years, with Keflezighi winning silver in the men’s marathon and Kastor bronze in the women’s race.

No other country won two medals in the marathon that summer, and in the four Olympics that followed Athens, Americans won nine Olympic medals in the distance events. Now, all of the top U.S. distance runners live and run at altitude, with most congregated in Flagstaff, Ariz., Park City, Utah, or Boulder, Colo.

“We did some things that got everybody’s attention,” said Larsen, a member of the national track and field Hall of Fame. “Everybody had kind of given up that they were going to be able to catch [the Africans].”

Since Chris Solinsky became the first American — and first non-African — to break 27 minutes at 10,000 meters in 2010, five U.S. men have done so. Yet if the Americans have caught the Africans, they haven’t passed them because they haven’t won a distance event in the last nine Olympics. And doing that will involve more than just running fast, since tactics and luck are just as important.

“One guy gets to win gold every four years. So it’s a lofty goal,” said Fisher, who trains in Park City, Utah. “Winning gold’s tough. And it’s not just East Africans you have to worry about.”

Cheptegei agrees. Despite holding the world record in two events, the Ugandan has won just once in four Olympic finals.

“Everybody who qualifies for the Olympic Games, you really have to respect them,” he said. “It’s not really a simple task.”

That’s because most Olympic finals are more tactical than fast, one reason why Cheptegei’s world record is nearly a minute better than the Olympic record. And while the Americans have learned to run fast over the long distances, they’re still learning to run smart.

In the 5,000 meters at Friday’s Los Angeles Grand Prix at UCLA, for example, Fisher couldn’t match a blistering 54-second final lap from Ethiopia’s Selemon Barega, finishing behind four Africans in 12:53.30. It was the sixth-fastest time in the world this year but only the fifth fastest at UCLA that evening.

“I gave myself too much ground to make up in the last 200,” said Fisher, who ran just behind the leaders for much of the race. “Great time [but] I wish I was a little more competitive with those top four guys. I can’t give them that space on the backstretch. Close that down and I think I’ll have a better chance.”

And he does have a chance, which isn’t something that’s often been said about American distance runners entering the Olympics. The competition has become so fierce, Fisher said he’s not even thinking about Paris since he first has to get through next month’s U.S. trials in Eugene, Ore., where the field is likely to feature six of the fastest 14 10,000-meter runners in the world this year.

“Nothing’s guaranteed. It’s a very hard team to make,” he said. “You can’t be focused on the Olympics because you’re getting ahead of yourself at that point. You know how it is it’s an Olympic year. Everyone’s focus is the Games.

“But you can’t overlook USA.”

Regardless of what happens in Eugene or Paris, that counts as progress.

“This sport is rich,” Barega said. “Sometimes one athlete wins, sometimes another athlete wins. Other athletes in America are coming. Not [just] Fisher. Many athletes in America. It’s good.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.