Column: Lakers documentary captures the legendary 1971-’72 championship team

Since the Lakers’ present isn’t much, it’s nice that there exists a heartwarming and inspirational story from their past.

Where there is history, there is hope.

The story is captured in a documentary film titled: “33STR8.”

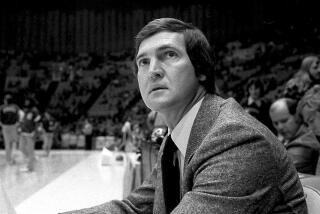

That was Bill Sharman’s license plate. It represented the Lakers’ record 33-game winning streak in the team’s 1971-72 championship season.

Sharman was the coach, architect, guardian angel, creative director, priest, rabbi and parole officer of a team that, in Los Angeles lore, has gone beyond legendary to near-sacred.

They held the film’s premiere Thursday night at L.A. Live. By one count, there were more than 500 in attendance. How many mattered less than who.

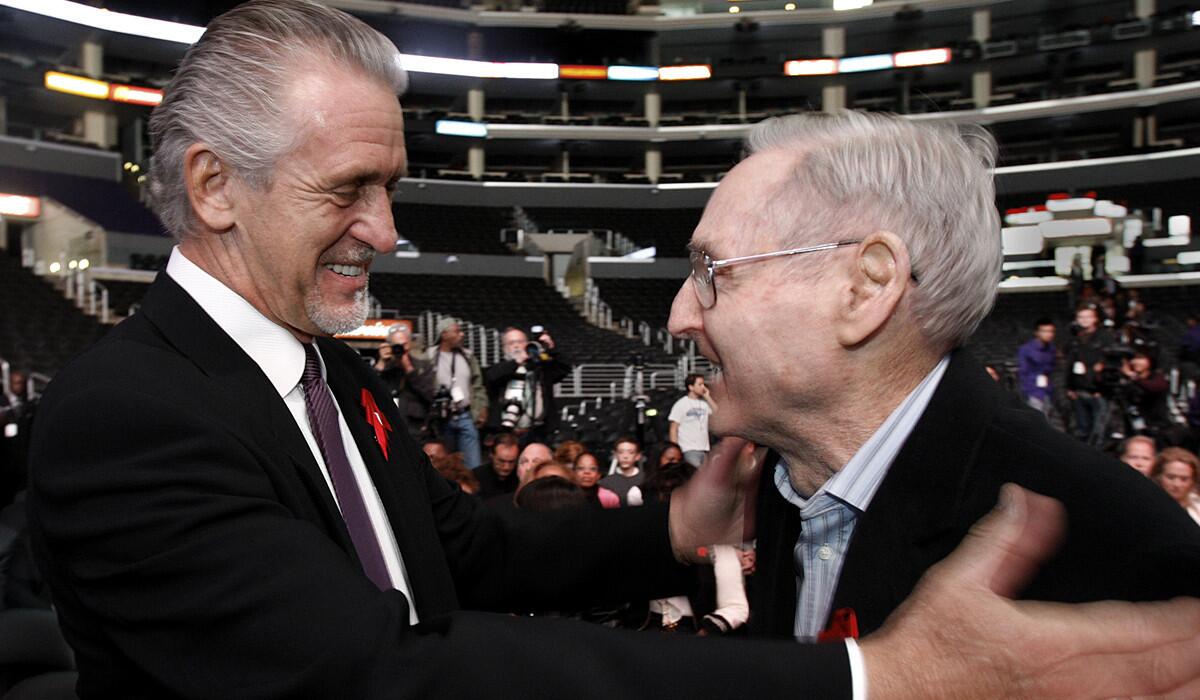

Jerry West was there. So was Pat Riley, Jim McMillian, Keith Erickson, Lynn Shackelford, Jamaal Wilkes, Lucius Allen, Norm Nixon, Mitch Kupchak, Bill Bertka and James Worthy, among others.

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, who would later become a Lakers legend in his own right — but was on the Milwaukee Bucks team that ended the winning streak at 33 on Jan. 9, 1972 — appeared on film to talk about how organized and meticulous Sharman was. Gail Goodrich was there on film too, talking about that first Lakers training camp in Hawaii, when Sharman took over the team.

“He ran us to death,” Goodrich said.

And then, there was the cherry on the top of the evening’s banana split. Bill Russell came down from Seattle, just to be there, “because of Bill.”

In this town, Russell was, is and always will be a wonderfully contradictory figure of the hated Celtics and a respected rival. So was Sharman, who played with Russell, before he got the Lakers coaching job for that 1971-72 season and carried the unthinkable even further for Lakers fans. He hired another ex-Celtic, K.C. Jones, as an assistant coach.

Russell appeared in the film, talking about Sharman’s stunning decision to have his players get out of bed on game days to take part in late morning shoot-arounds to loosen up. That decision was stunning because the center on Sharman’s team was one Wilt Chamberlain, who often didn’t get to bed until 7 a.m.

Russell told the story about the first day of the shoot-arounds. The team bus waited and Wilt didn’t arrive. So Sharman sent a trainer to Wilt’s hotel room.

“The guy knocked on the door,” Russell related, “and Wilt told him to tell Sharman he would only go to the arena once that day and to give Sharman the choice — now or for the game.”

Then Russell laughed his light-up-the-room cackle and all seemed well in the world.

West entertained the crowd with stories about how an unkempt, under-showered Chamberlain would arrive for games directly from a beach volleyball game, feet in flip-flops, hair full of sand, telling everybody what a great volleyball player he was.

“And then he’d go out and get 18 rebounds,” West said.

Erickson, who actually was a great volleyball player, confirmed that Wilt was the only person who thought Wilt was a great volleyball player.

Riley, who was a scrappy reserve guard on that ‘71-72 team before coaching the Lakers to more greatness in the Showtime era, is now president of the Miami Heat. In the spring of 2013, the Heat reeled off a winning streak that threatened to catch the Lakers’ 33 before it was ended at 27.

Riley was asked where he stood, emotionally, when his current team was pursuing the record of his past team.

“Wouldn’t have happened,” he said. “They all would have gotten the flu.”

The stories flowed, the crowd appeared mesmerized.

Shackelford, the former UCLA star, was Chick Hearn’s broadcast sidekick that season.

“It was a tough season for me,” he said. “Chick never let anybody else talk unless the Lakers were down by 10 points or more.”

Bertka, longtime Lakers scout and assistant, told stories about the quirkiness of owner Jack Kent Cooke, a multimillionaire, who would walk 300 yards to pick up a penny in a parking lot.

“Bill [Sharman] wanted a new film projector,” Bertka said. “But Cooke said no, it would cost too much.”

So Bertka devised a way to keep the old 16-millimeter machine running by jamming a pencil into a loose spot.

McMillian was a second-year player out of Columbia, who was thrown into the starting breach when an aging, injured Elgin Baylor retired early that season. McMillian had special memories of playing the Celtics in Boston.

“Bill would want to hold a practice,” McMillan said, “and the Boston Garden was always locked. Red Auerbach would say he tried, but he couldn’t find the maintenance guy who had the key.

“Then we’d get to the game and our locker room was like a sauna. The Celtics locker room was always nice and air-conditioned. Auerbach could never seem to find the building engineer to get ours fixed.”

Russell cackled.

During the evening, Sharman was called everything from “magical” to the “first Laker Zen master.” Not only had he coached that ’72 team to a title, but he was a Lakers executive for five more championships.

The film project was in full stride when he died, at 87, from complications of a stroke in October last year. His wife, Joyce, kept the project going, and it will be shown soon on Time Warner Cable.

The film has a theme song, written and sung by Kipp Lennon of the rock band Venice. Its title is “How You Play the Game” and one of the main lyrics is perfect for the ‘71-72 Lakers: “Once in a lifetime, the stars get aligned.…”

The film is light on action footage and heavy on interviews, which seems to work.

One warning: For those who tend to get queasy, sportswriters are pictured and quoted throughout.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.