U.S. Open’s grit is linked with that of Jimmy Connors

The U.S. Open tennis tournament begins Monday. Describing it is almost as hard as playing in it.

It is the most difficult tournament in the world to win, and that certainly includes the other three majors. Australia is friendly, exotic in its distance, a fresh start to a new year. Paris is great food, interminable rallies and dirty socks. Wimbledon is prestige, royalty, stiff upper lips and strawberries and cream.

The U.S. Open is everything they aren’t.

It is New York. Push and shove. Outta my way, buddy.

It is noisy, dusty, often rainy, always windy, never predictable, seldom logical. The players are exhausted after nine months of grinding. They don’t want to be there and they have to be. The courts are hard, the crowds are harder, the stakes are high and the lid on the pressure cooker is loose.

The U.S. Open is where Serena Williams once marched up to a linesperson, offered to jam a tennis ball down her throat and was heard by dozens of fans sitting nearby. Many of them cheered.

Let’s simplify. Let’s reduce our description of the U.S. Open into a name and a number:

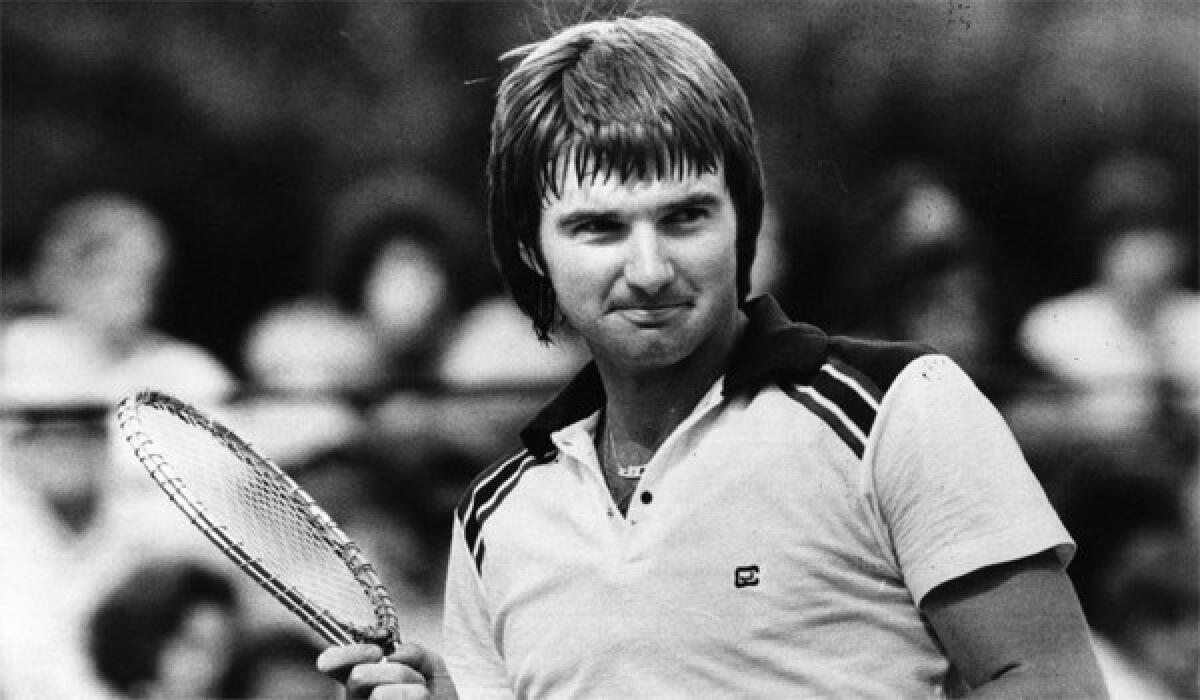

Jimmy Connors, 1991.

Only three men have won five U.S. Open titles in the modern era — Pete Sampras, Roger Federer and Connors. Connors didn’t win in ’91. He just changed the landscape of the tournament forever that year.

We sit at a bar, sip drinks, and it all comes racing back to Connors.

“I didn’t win in ‘91, and here we are, talking about it,” he says. “It’s almost better that way.”

He never officially retired. No big, fancy news conference. He played on and off after the ’91 U.S. Open, even in the ’92 Open. But after ‘91, it was effectively over. He knew it. No regrets.

“I left a lot of DNA on that court in ‘91,” he says, “and I don’t want any of it back.

“It was tough, walking away from the game. But after ‘91, that was it. That was good enough.”

Tennis fans will agree. They either loved Connors or hated him. No middle ground. Nor was there an argument about what he did in ’91.

He had missed most of 1990 because of a wrist injury. He calls it a year of depression. He found a surgeon who tried a different procedure and told him to “get your butt back out there.”

So he did. But his third-round endings in both the French and Wimbledon in ’91 gave little hint of what was to come in New York’s concrete jungle. He was, after all, about to turn 39. The resume said that five previous titles, and three other majors, gave him a chance. The age, the wrist and his No. 174 ranking said otherwise.

It began on a Tuesday night in Armstrong Stadium, then the main stadium. Now, it is the 22,547-seat Arthur Ashe high-rise. Tickets on top should come with binoculars. Night tennis was popular, but nowhere near what it was about to become.

The first-rounder had a ring to it: Connors versus McEnroe. This was John’s brother, Patrick.

“I knew I needed to get stuck in a tournament,” Connors says now, meaning get past the first round. “I figured fans hadn’t seen me for a while, and once they did, they’d get me going.”

McEnroe soon led, two sets to love, three games to love and 40-love. Armstrong emptied. It was late. The match hadn’t even started until 9:15.

“I saw my friends, Ilie Nastase and Jose-Luis Clerc, get up and leave,” Connors says.

Their loss. Connors won that game, then the set, 6-4, and finally the match. It finished at 1:35 a.m., and those who had stayed did exactly as Connors needed. They pulled him through, made him play young again.

“The corporates left and the people in the high seats came down,” Connors says.

The story exploded. It was New York. Connors won his next two matches, and the city that loves an underdog, because much of it is one, loved him anew. It was the old man and the sea, and those across the net from Connors were big fish, hopelessly hooked.

In the round of 16, he played Aaron Krickstein, 15 years younger and as high as No. 6 the year before. It was Sept. 2, Connors’ 39th birthday.

“We were buddies,” Connors says. “We played gin, practiced together.”

Connors trailed Krickstein in the fifth set, 5-2. The end was near.

“We both sat down at that break,” Connors says, “and we were both dead. I remember looking at the crowd. They were having a beer and a hot dog and demanding more from us.”

They got it. Connors held serve, Krickstein faltered and the impossible run continued.

“Strange,” Connors says now, “but I haven’t seen or talked to Aaron since that night, 22 years ago.”

Connors beat Paul Haarhuis in the quarterfinals, firing up the crowd by returning four straight overheads from Haarhuis before hitting a winner. Next was reigning French Open champion Jim Courier. It was the semifinals, and it was over. Finally.

“He was smart and good,” Connors says. “He didn’t miss a ball, and he never let the crowd in it.”

Connors, 60, will spend a couple of days at this year’s U.S. Open, doing corporate work and making appearances. He probably will wander over to Armstrong Stadium one night, where it will be loud, boisterous, wild and fun. From there, he will be able to hear them rocking at nearby Ashe.

It will be U.S. Open tennis, its own brand of sports lunacy. He’ll feel it, hear it, and get great satisfaction from knowing his role in why it is like that.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.