Column: Sergey Kovalev, a ‘nasty guy’ in the ring yet traumatized by tragedy

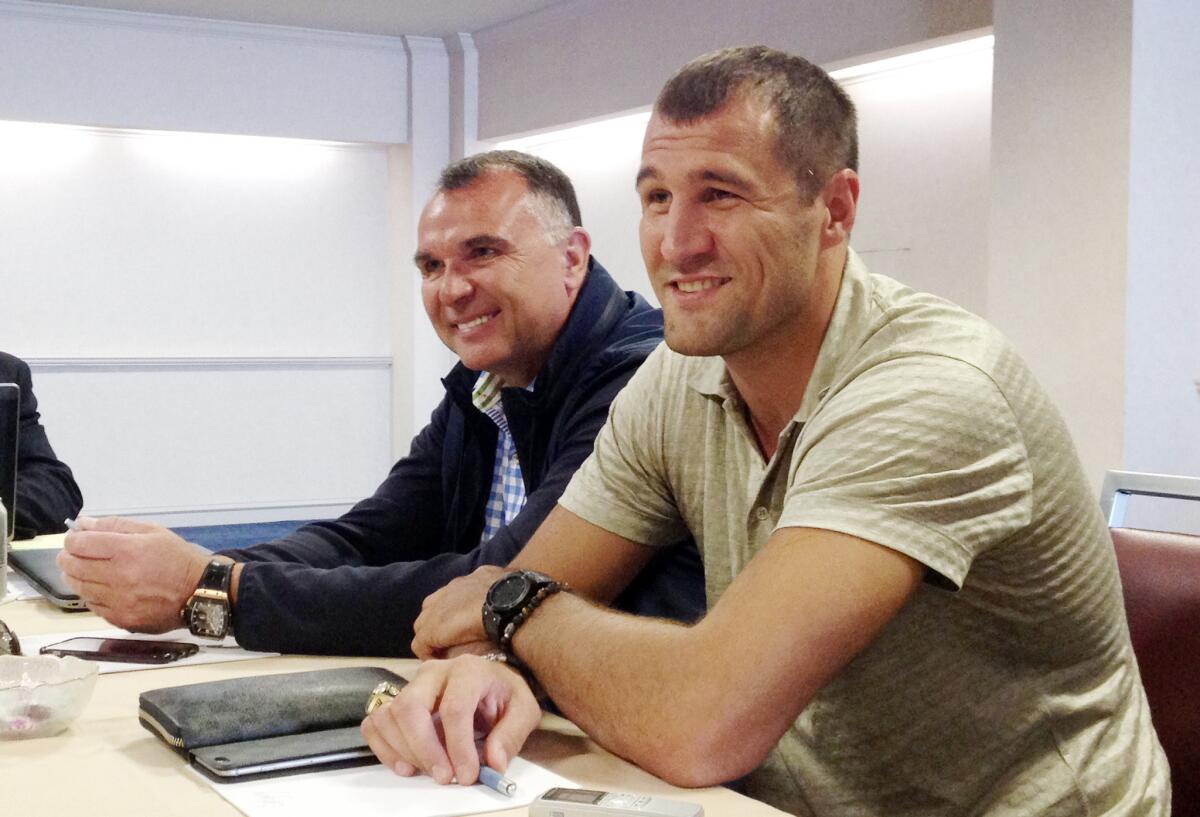

Sergey Kovalev had some business to attend to in order to set up the most important night of his boxing career.

A fight in defense of his light-heavyweight championships against Isaac Chilemba was a necessary step for Kovalev to secure a Nov. 19 showdown with Andre Ward at the T-Mobile Center in Las Vegas.

The bout against the overmatched Chilemba was not remarkable.

A telephone call Kovalev made afterward was.

On the other line was a different fighter’s mother.

Four-and-a-half years earlier, Kovalev had stopped Roman Simakov in the same Ekaterinburg arena in which he outpointed Chilemba. At the time, Kovalev and Simakov were both relatively unknown prospects.

Simakov, 27, was knocked unconscious and slipped into a coma. He never woke up.

The incident traumatized Kovalev, and now he was asking Simakov’s mother if he could financially assist her family.

“I’m not doing it for you, I’m not doing it for anyone else, I want to do it for myself,” Kovalev told her, according to his longtime manager, Egis Klimas.

How Kovalev has maintained his menacing in-ring persona while so burdened is one of the sport’s great mysteries.

The 33-year-old is nicknamed “Krusher,” a reference to a violent style of fighting that has resulted in him knocking out 26 of his 31 opponents.

Kovalev’s 2011 fight with Simakov didn’t change how he fought. If anything, he’s a more vicious fighter now. Age has compromised his ability to move around the ring, prompting him to plant his feet and make a greater commitment to his trademark power punches.

“He’s a nasty guy,” said Kovalev’s trainer, John David Jackson.

Kovalev showed that in his rematch with Jean Pascal this year, when he acknowledged he purposely didn’t knock out his trash-talking Canadian challenger because he wanted to inflict more punishment. Pascal’s trainer stopped the fight after the seventh round.

This isn’t normal. Even in a sport as brutal as boxing, it’s common for a fighter to temper his aggression out of fear of hurting an opponent.

Former super featherweight champion Gabriel Ruelas was never the same after he killed Jimmy Garcia in 1995, pushed into an early retirement because he said he couldn’t shake the image of his fallen opponent in the opposite corner.

Roy Jones Jr., the best fighter in the world in the 1990s, was considerably less menacing after he saw his friend Gerald McClellan absorb a savage beating that resulted in a blood clot in his brain.

Kovalev won’t talk about how he has managed to compartmentalize Simakov’s death.

“I already forgot about [that] day,” he said.

He won’t revisit the incident, which clearly remains a sensitive topic for him.

“I already forgot,” he said. “I say it again.”

The people around him have done what they could to protect him.

“We’re trying not to remind him about it,” Klimas said.

Kovalev has spoken publicly about his fight Simakov only once, during an interview with Yahoo Sports earlier this year that was arranged by Klimas.

During the interview, Kovalev said that as he was pounding Simakov he wondered why the referee didn’t stop the fight. When he learned of Simakov’s death, he said, “I was lost.”

Kovalev wanted to reach out to Simakov’s family, perhaps even attend the funeral. Klimas, who knew Simakov’s family blamed Kovalev for what happened, told him not to.

In the article, Kovalev said he returned to the ring because he had to provide for his family.

“He had a very, very hard time,” Klimas said. “For six months, he had the worst time he ever had in his life.”

That’s not hard to imagine. Kovalev comes across as thoughtful and sensitive when he isn’t wearing a pair of gloves.

During a recent interview with The Times, he explained that he wrote an autobiography in Russian because he wanted to inspire young people in his homeland who shared his hardscrabble background. He spoke slowly and looked into the distance as he recalled his mother and siblings sharing packets of bread with other families. He expressed an appreciation for the United States, which offered him the chance to become a millionaire.

“Russia made me strong,” he said. “America gave me the opportunity to get my dreams. I love both countries. One country gave me what I have in my head, in my heart, in my spirit, America gave me opportunity for a comfortable life, live my dreams.”

Klimas said he spent considerable time convincing Kovalev he wasn’t at fault in Simakov’s death.

“You could be in the exact same situation,” Klimas said he told Kovalev. “My advice was: ‘You can live with it all of your life or you can let it go. No matter what you do, you’re not going to bring that person back.’”

Klimas said Simakov’s mother told Kovalev she still holds him responsible for her son’s death, but she accepted his charity. The manager is hopeful Kovalev might finally be at peace.

“Right now, he’s completely out of it,” Klimas said.

Being alongside Kovalev for the last five years has also made Klimas confident that his fighter won’t be unraveled by the mind games Ward will try to play. The psychological warfare has already started, with Ward refusing to shake Kovalev’s hand before a news conference last month.

“People like Andre Ward can’t get into his head to frustrate him,” Klimas said. “You can’t control this guy.”

It makes sense. Kovalev had to block out something considerably worse to reach this point.

Follow Dylan Hernandez on Twitter @dylanohernandez

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.