At Manzanar, fishing was the great escape

- Share via

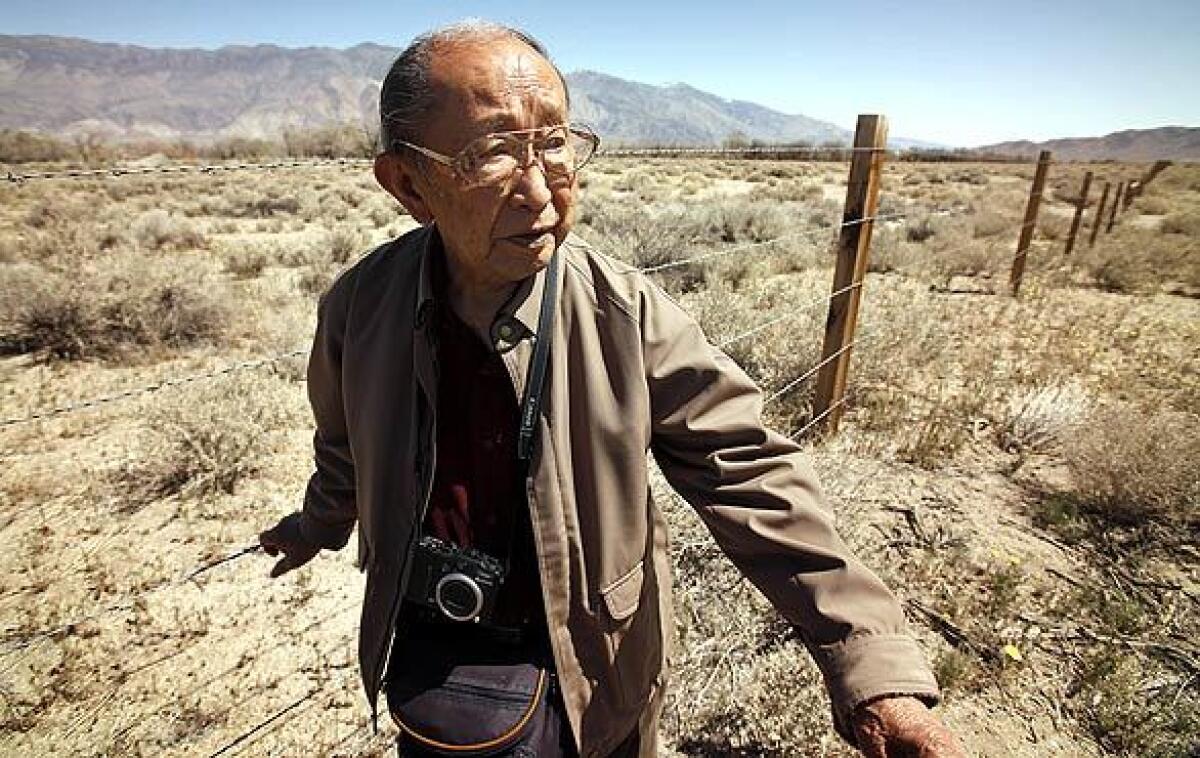

Reporting from Lone Pine, Calif. — Sets Tomita pauses at Manzanar’s southwest boundary and scans the high desert wistfully.

It’s his first visit to this precise location since the World War II- era detention facility for Japanese Americans closed in 1945.

The guard tower is gone, but Tomita walks over its concrete foundation, stirring up dust. How his family hated dust, and the afternoon winds that drove clouds of it through a camp that broiled in summer and froze in winter.

But Tomita, 77, harbors fond memories of this place too.

His gaze is to the southwest. Out there, in the shadow of the Sierra Nevada’s eastern slope, tree-lined George Creek snakes across the desert like a verdant oasis.

It beckons today as it did then, but today Tomita can go freely. Sixty-seven years ago, with armed guards on high alert, the journey required darkness for cover, a stealthy crawl beneath barbed wire and a fugitive-like escape across boulder- and shrub-mined terrain.

Once at George Creek, as morning sunlight flooded the Owens Valley, the Tomita kids would spend long days beneath tree cover, fishing for rainbow trout with poles made of willow branches and hooks fashioned from paper clips.

“It kind of reminded me of Huck Finn,” recalls Tomita, who was 10 and his oldest brother 14 when they first went AWOL. “It was exciting. As a young kid you don’t think about the consequences. My brother was going to take care of us, so we just followed him out.”

As the Manzanar National Historic Site prepares for Saturday’s 40th annual pilgrimage, a commemoration of what was endured during the war, and as the region welcomes thousands for the opening of trout-fishing season, the detention facility is being fondly remembered by some as a secret fishing lodge.

In part because some of the 11,000 internees typically sneaked out alone or in small groups and kept their exploits secret, it’s impossible to know just how many escaped to ply local creeks or high-mountain lakes. But Cory Shiozaki of Gardena, who has been working since 2004 on a documentary film titled “From Barbed Wire to Barbed Hooks, Fishing Stories From Manzanar,” estimates that as many as 400 would occasionally slip out of camp, mostly for a day or two but sometimes for a week or longer.

Trout fishing symbolized freedom and adventure.

“We fried it and it sure tasted good,” recalls Archie Miyatake, 84, who was 16 when he and his family were relocated from Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo district to the 6,000-acre camp. “Especially since it was fish we weren’t supposed to catch.”

Shiozaki began his project after he read a Los Angeles Times story about an internee then known only as Ishikawa. In a portrait captured by Miyatake’s father, Toyo, a weather-worn Ishikawa displays a stringer of six golden trout. They were specimens from high-altitude lakes, possibly on the Sierra’s western divide.

Shiozaki later determined that Ishikawa’s first name was Heihachi. He was 53 when he arrived in 1942, and he remains the most ambitious known angler in Manzanar’s mostly dark history.

“Security was high during the first 18 months, so they would time their escape as the search lights were panning left to right, just like in ‘Hogan’s Heroes,’ ” Shiozaki says, prompting laughter from Tomita, Miyatake and Jiro Matsuyama, gathered for an afternoon tour of their escape routes and nearby fishing spots.

Though it was reasonably easy to escape, there werewere consequences.

One internee, trying to sneak out during daylight, was thwarted by gunshots aimed at his feet.

Another was captured while making his way back to camp. MPs confiscated his equipment and fish, and marched him into camp at bayonet-point.

A 15-year-old was jailed for a week for sneaking off to fish.

Only one internee is known to have died while on a fishing expedition. An elderly artist-angler named Giichi Matsumura accompanied others into the majestic wilderness beyond Mt. Williamson, but lagged behind to paint. An unexpected snowstorm blanketed the region. The fishermen hunkered for hours in a cave and could not find Matsumura after the storm passed. His remains were discovered weeks later by hikers.

On this increasingly blustery afternoon, Tomita, Miyatake and Matsuyama are walking the camp’s perimeter, which is still defined by a 6-foot wire fence.

Tomita says he harbors no bitter feelings about his family’s three-year detention. In fact, he says, pangs of guilt coursed through the Japanese American community after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941.

Beginning in 1942, the U.S. government ordered 110,000 Japanese Americans and resident Japanese aliens to be placed in 10 military-style camps in Western states.

Tomita was taken to Manzanar, eight miles north of Lone Pine along U.S. 395, with his parents, two older brothers, two younger brothers and a sister.

If he experienced guilt, it did not interfere with repeated escapes. The Tomitas left after dusk via the southwest corner because the banks of a small creek bed offered cover.

Miyatake chose the western fence near the cemetery, and fished mostly in Shepherd Creek, to the north, with a cousin’s husband.

“One time he caught so much fish that all the bags were filled up, so he stuck them in his pockets,” Miyatake says.

Matsuyama was older and more fortunate. He was manager of the camp’s off-site reservoir, so he had a car and freedom to come and go.

“I always carried a fishing pole under the seat of the car,” he says. “And whenever I saw a fish I’d run to the car, grab my pole, and run into the bushes.”

Matsuyama, 88, was approached often by internees offering payment to sneak them out. He refused, but later disguised them as reservoir project helpers and delivered them five rugged miles -- a full day’s hike -- to routes leading to high wilderness.

“The MPs didn’t know what was going on,” Matsuyama says, waving a hand as if shooing a fly.

Camp life was demoralizing, though. Living quarters were cramped. Communal bathrooms afforded no privacy.

Internees had a volunteer police and fire department, a school and a baseball diamond. Adults planted gardens and some had jobs farming, making camouflage netting or extracting rubber from guayule plants.

But barracks-style living broke down the family structure and internees entertained no notions of actual escape. “We’re Japanese; you can spot us a mile away,” says Tomita, who lives in Northridge.

There was only one place, west of U.S. 395 and opposite civilization, where, Miyatake remembers, “the air just tasted better.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.