Column: Kyla Ross, UCLA’s most dominant gymnast, continues to keep fans spellbound

Her days of celebrity were behind her. Or so she thought.

Seven years after what was thought to be her crowning achievement, Kyla Ross has more than 400,000 followers on Instagram and 200,000 on Twitter.

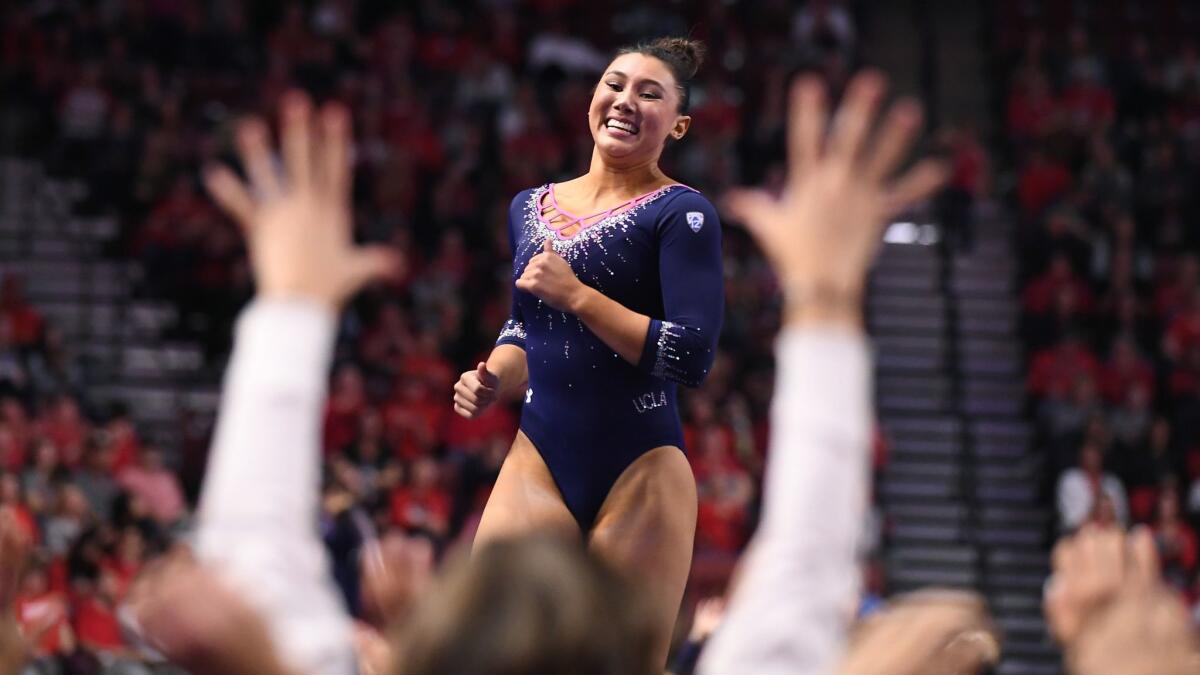

If Katelyn Ohashi’s viral floor routine initially attracted the capacity crowds that watch the UCLA gymnastics team, it’s Ross who has kept the audiences spellbound by posting perfect scores on a weekly basis.

Ross has become the most dominant performer on the most popular gymnastics team in the country, which will defend its national championship starting Friday at the NCAA championships in Fort Worth.

She has become a hero to hundreds of aspiring gymnasts who flocked to Pauley Pavilion this season holding up signs with her name and waiting in lines for her autograph.

“Just seeing the number of young girls that are watching and look up to us is super amazing,” Ross said.

This isn’t supposed to happen to Olympic gymnasts, who typically peak early and fade away. Ross is enjoying a resurgence as a 22-year-old junior.

Moving on from the Olympics can be difficult, especially for athletes as successful as Ross. She was 15 as a member of the “Fierce Five,” the U.S. team that won a gold medal at the 2012 London Games.

That team included Jordyn Wieber, now a volunteer assistant coach at UCLA.

“It’s a really weird transition,” Wieber said. “If you decide you want to be an Olympian at a young age, like I did, it’s like you work your whole life for this one moment. And then after that moment happens, you ask yourself, ‘What now? How do I top that in life?’”

Ross’ parents did what they could so their daughter wouldn’t have to endure such an existential crisis.

“That’s what you do, it’s not who you are,” said her father, Jason. “Don’t let it define who you are because it all comes to an end.”

Jason experienced this firsthand. He played baseball and football at the University of Hawaii and pitched for six seasons in the Atlanta Braves farm system.

Kyla was fortunate there was a gymnasium that trained elite athletes relatively close to her family’s home in Aliso Viejo. As she prepared for the Olympics, she remained in her local public high school, Aliso Niguel, which accommodated her schedule.

The Ross family also looked ahead and decided that regardless of whether Kyla made the Olympic team, she would one day attend college.

So when her “Fierce Five” teammates, including Wieber, turned professional to capitalize on their Olympic glory, Ross remained an amateur. At competitions that included monetary rewards, Ross signed over her prize money to charity.

Planning ahead spared Ross from wondering what she would do next. She was already familiar with the college gymnastics scene, not only because she knew many of the athletes from the elite circuit but also because she attended meets at UCLA.

If she experienced any post-Olympics uncertainty, it was over a sudden 4 1/2–inch growth spurt. In a matter of months, she shot up from 5 feet 2 to 5 feet 7.

“I didn’t really take that much time off after the Olympics,” Ross said. “At most, I took like two to three weeks off. Not stopping and continuing to train really helped me ease growing that much in a short period of time.”

But the task was more difficult than Ross described. Wieber explained why.

“It’s an adjustment, especially for bars,” Wieber said. “When you compete at the elite level, the bars have to be a certain distance apart. For college, you can make the bars wider, you can make them closer, depending on how tall you are. It’s hard because it not only changes your skills, but it also changes your timing.”

Ross adjusted, Weiber said, with “a lot of rough days in the gym.”

“A lot of times what people see from gymnastics is what they see on TV. There’s so much behind the scenes that goes on,” Weiber added. “So many times, we fall and get back up, fall and get back up, again and again and again, learning how to be successful and learning how to hit your skills.”

Ross was a five-time medalist at the world championships, claiming silver in all-around, uneven bars and balance beam in 2013, as well as team gold and all-around bronze in 2014. When he graduated from high school, she delayed her entry into UCLA by a year to dedicate herself to making the U.S. team for the 2016 Olympics at Rio de Janeiro. (Set back by injuries, she abandoned the pursuit a couple of months before the Olympic trials.)

As a college freshman, Ross was the national champion in the balance beam and the co-champion in the uneven bars, which made her the first gymnast to ever win Olympic, world championship and NCAA titles.

Last year, her clutch performance on the balance beam helped the Bruins win the national championship in dramatic fashion.

“She’s just so magnificent,” UCLA coach Valorie Kondos-Field said. “I love the example that she not just gives our athletes, but gives to everyone that watches that it’s OK not be perfect. She’s what the sport is all about, get your ego out of it and just do the best you can in the moment.”

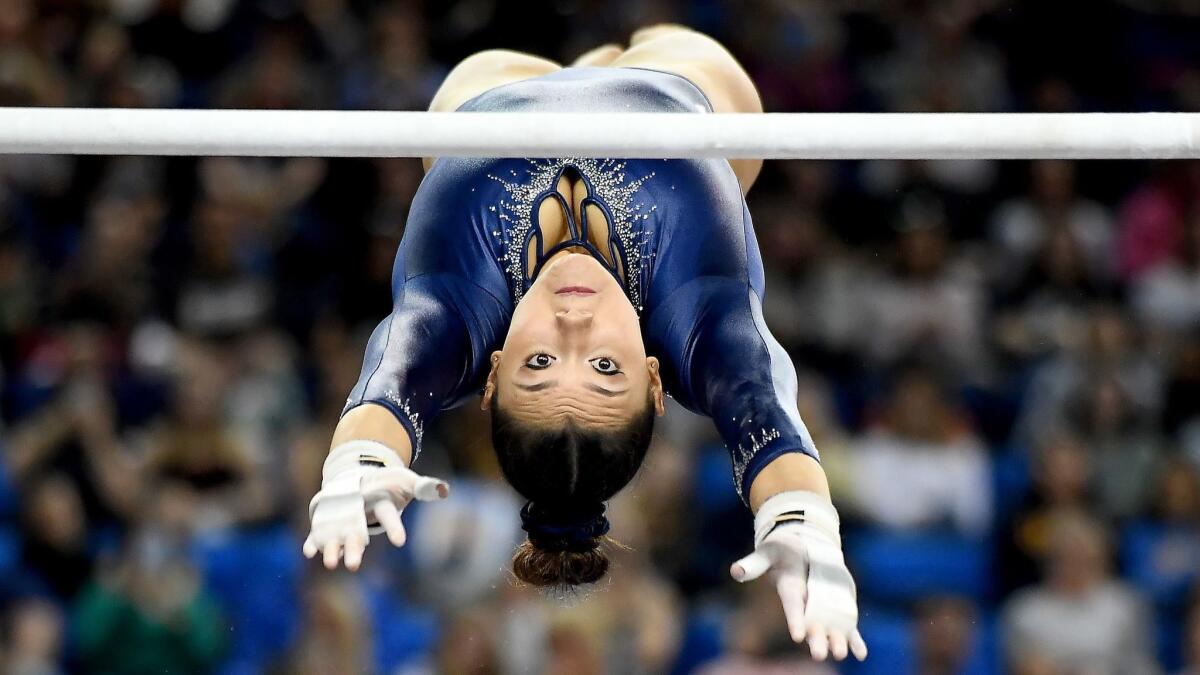

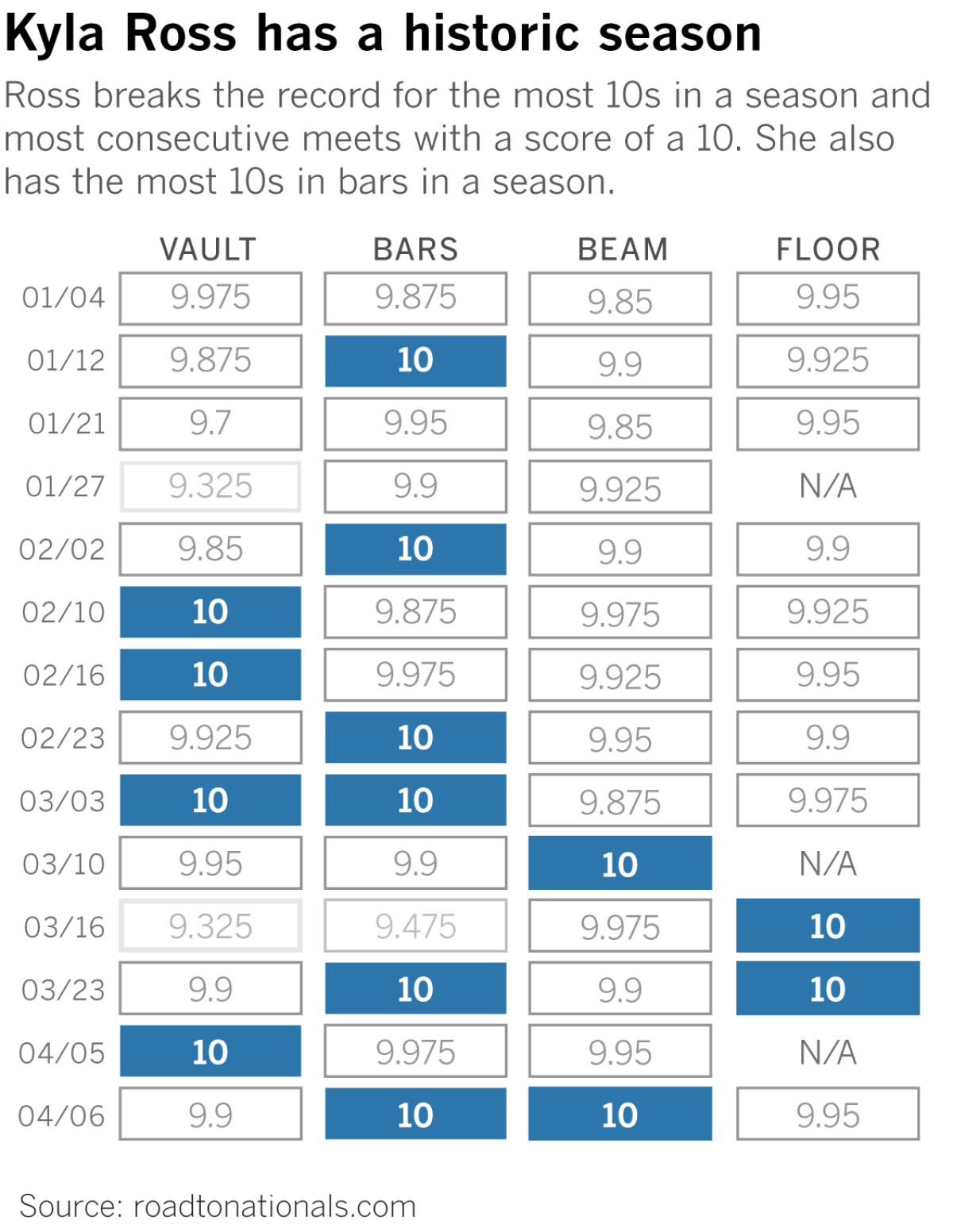

Ross this year has been the best college gymnast in the country. She has earned 13 perfect 10s, including at least one in each of the last 10 meets. She is the first college gymnast to ever complete two “Gym Slams,” meaning she has twice scored a perfect 10 on each apparatus — uneven bars, balance beam, vault and floor exercise.

All this while working toward a degree in molecular, cell and developmental biology.

Her performances have completely overshadowed the revelations she and teammate Madison Kocian made in August, that they were abused by former USA Gymnastics physician Larry Nassar.

“It’s really cool to see how college gymnastics has stepped into the spotlight this year,” Ross said. “It’s been really great to see that positive side of gymnastics in the media.”

Ross now has the experience and perspective to appreciate what she’s accomplishing. In retrospect, she didn’t have that while chasing her Olympic dreams.

Of the Olympic experience, she said, “It still probably hasn’t sunk in that much. Definitely as I grow older, I’ll realize it and cherish it a little bit more.”

Asked to recall the moment she was informed she made the Olympic team, she said, “I honestly don’t even remember it that much.”

She offered a similar answer when asked what it was like to be on the medal stand when the U.S. national anthem played.

“That’s another moment where I barely remember anything,” she said. “It’s like one of those things where you kind of black out because it’s a very surreal moment.”

And now?

Ross said she enjoys competing more because she has come to view gymnastics as something she gets to do rather than something she has to do. She looks forward to sharing laughs in a team environment that she rarely experienced as an elite gymnast. Ross is particularly humbled by the number of girls who idolize her and her teammates.

“I feel like it’s cool to see how the fans are so connected to us,” she said.

She’s been granted another moment in the spotlight. This time, she has the wisdom and perspective to take it all in.

Sign up for our daily sports newsletter »

Follow Dylan Hernandez on Twitter @dylanohernandez

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.